María Arias Bernal

María Arias Bernal, also known as María Pistolas (1884–1923), was a schoolteacher who was an agitator in the Mexican Revolution under Francisco I. Madero, president of Mexico 1911–1913, until his assassination in a counter-revolutionary coup by Victoriano Huerta.[1][2] Arias is noted for her defense of Madero's tomb in Mexico City, despite the threat of the Huerta regime.

María Arias Bernal | |

|---|---|

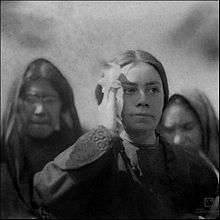

María Arias Bernal, 1914 (foreground) | |

| Born | 1884 Mexico City, Mexico |

| Died | 1923 Mexico City, Mexico |

| Nationality | Mexican |

| Other names | María Pistolas |

| Occupation | Schoolteacher |

| Known for | Fought in the Mexican Revolution |

Biography

Born in Mexico City in 1884,[3] Arias Bernal received her schoolteacher's diploma with honors in 1904. She began teaching and in 1910 became a school superintendent.[4] Eulalia Guzmán, Dolores Sotomayor and Arias founded the Corregidor de Querétaro Vocational School with a curriculum of reading, writing, arithmetic, cooking, drawing and sewing designed to help women improve their economic circumstances.[5] Arias served as deputy headmistress for a short period of time, but soon she joined the Madero movement. She participated in the educational literacy drive and became the private secretary of Sara Pérez de Madero,[1] wife of the president.[4] Together with Elena Arizmendi Mejia, she promoted the work of the Neutral White Cross.[1]

When President Francisco I. Madero was captured, Arias and Eulalia Guzmán attempted a meeting with coup leader, Victoriano Huerta, to plea for the life of the president and his vice president.[5] Following Madero assassination, she founded the Women's Loyalty Club (Club Femenil Lealtad) in order to provide support for the cause around Madero's tomb, hoping to overthrow the Mexican president Huerta. Every Sunday, she arranged demonstrations in La Piedad in the north of Mexico City around his tomb.[6] Arias purchased a printing press to print flyers[4] and she and Julia Nava de Ruisánchez distributed anti-Huerta manifestos throughout the city.[5] In 1913, she was arrested after attacking Jorge Huerta, son of the president, who was caught vandalizing the grave of Madero.[4]

When General Álvaro Obregón arrived in Mexico City in 1914, he asked who had taken care of the tomb of the deceased president. Recognizing that it was María Arias, he took out his gun, raised it up and declared: "Those men who are able to take up arms but refused to do so for fear of abandoning their homes and their children, have no excuse. I abandoned my children without hesitation in order to serve the national cause. As evidence that I am able to admire the valour of others, I hand my pistol to señorita Arias, because she is the only one worthy of wielding it; this gun, which has served in defence of the popular interests is as good in her hands as it has been in mine."[6][7] As a result, the press called her "María Pistolas" (María Pistols).[1]

María Arias Bernal died in November 1923[4] in Mexico City when she was 39 years old.[8]

Movie

Maria Arias Bernal's life was immortalized in film when Maria Pistolas, a Mexican film directed by Rene Cardona, was released in 1963 by Cinematografica Filmex S.A. and Estudios America. Arias Bernal was played by Dolores Camarillo. The movie was released in the United States in 1965.[9]

References

- Impacto de la Revolución mexicana. Siglo XXI Editores. 2011. pp. 97–. ISBN 978-607-03-0250-3.

- "María Pistolas" (in Spanish). SDPniticias-com. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- Erika Cervantes. "María Arias Bernal, "María Pistolas"" (in Spanish). CN cimacnoticias. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- Garcia Romero, Yolanda (May 1986). "From Rebels to Immigrants to Chicanas Hispanic Women in Lubbock County" (PDF). Texas Tech University. Texas Tech University. pp. 18–20. Retrieved 20 March 2015.

- Mitchell, Stephanie E. (editor); Schell, Patience A. (editor) (2006). The Women's Revolution in Mexico, 1910-1953. Lanham [Md.]: Rowman & Littlefield Pub. pp. 23–24. ISBN 978-0-7425-3730-9. Retrieved 19 March 2015.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Lear, John (2001). Workers, Neighbors, and Citizens: The Revolution in Mexico City. U of Nebraska Press. pp. 299–. ISBN 0-8032-7997-3.

- Kantaris, Elia Geoffrey; O'Bryen, Rory (2013). Latin American Popular Culture: Politics, Media, Affect. Boydell & Brewer Ltd. pp. 262–. ISBN 978-1-85566-264-3.

- "Maria Arias" (in Spanish). Buenas Tareas. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0279949/