Mannin (journal)

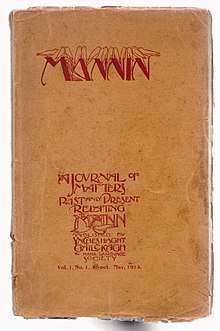

Mannin: Journal of Matters Past and Present relating to Mann was an academic journal for the promotion of Manx culture, published biannually between 1913 and 1917 by the Manx Society, Yn Cheshaght Ghailckagh. It was edited by Sophia Morrison, with the assistance of William Cubbon.

Background

Mannin was the society journal of the Manx Language Society, Yn Çheshaght Ghailckagh, (which changed its name to "The Manx Society" in 1913, to distance themselves from the apparent concern with language only).[1] The journal took forward the aims of the Society laid out by Arthur William Moore at its establishment in 1899:[2]

"Though called the Manx Language Society, it should, I think, by no means confine its energies to the promotion of an interest in the language, but extend them to the study of Manx history, the collection of Manx music, ballads, carols, folklore, proverbs, place-names, including the old field names which are rapidly dying out. In a word, to the preservation of everything that is distinctively Manx, and, above all, to the cultivation of a national spirit".

The Manx Society was created very much within the Pan-Celtic wave of revivals of Celtic national identities during the 19th and early 20th centuries. "Manx Nationalism" was expressed by Morrison as a key aim of both the society and of Mannin in particular.[3] However, unlike the Celtic developments in Ireland and elsewhere at that time, the society and Mannin displayed the Manx ease with a dual identity, as both Manx and British, which was borne out in the content of the journal, such as in the articles in support of The Great War.[3]

Publishing

Mannin was published by The Manx Society, by L. G. Meyer in Douglas. Its first issue was released in May 1913. The expenses of the publication were met by Morrison, who had inherited wealth from her parents, her father having been a successful merchant in Peel.[4]

In order that the journal and its cause of Manx Nationalism should be taken seriously, great care was taken with the publication, including printing on good quality yellow paper ("yellow is supposed to be the Celtic colour", commented Morrison),[5] and a leading artist commissioned to do the illustrations. The artist selected eventually was Archibald Knox, although this was only due to the fact that Morrison's first choice, Frank Graves, had turned the commission down.[3] Morrison was unhappy with Knox's illustration of the first issue's front cover as he illustrated it with birds rather than the Viking ship suggested by Morrison.[3]

The journal saw eight issues under Morrison's editorship. The material for a ninth issue was ready upon her death at the age of 58 on 14 January 1917. This ninth and final issue was edited by Mona Douglas and released in May 1917, with extra material being included to commemorate Morrison's life and work, including pieces by her friends and colleagues and protégés (including Cushag).[6] In this edition, Mannin was identified as Morrison's "greatest literary task".[7]

Content

The journal covered a wide variety of Manx cultural concerns. An analysis of the nine issues shows the frequency of topics that appear in Mannin as follows:[3]

- Music, folklore / oral history

- History, politics, poems, and prose in standard English

- "Manx Worthies" – Biographies of significant people relating to the Isle of Man

- Natural history

- Pieces about Manx Gaelic

- Poems and prose in Anglo-Manx

- Pieces in Manx Gaelic

Morrison wanted to ensure that the content reflected an active cultural force and that the journal form a rallying point for cultural nation building. The journal notably garnered contributions by well known and respected academics of the day (such as E. C. Quiggin at the University of Cambridge and Sir John Rhys at the University of Oxford) which lent weight to the publication. Morrison also wanted to address political issues with bearing on the island, such as in articles like "Should our National Legislature be Abolished?" in the penultimate edition of Mannin in November 1916.[3][8]

In contrast to contemporary work on Manx culture (such as through the government-sponsored Manx Heritage Foundation), Mannin was not overly concerned to publish much in Manx Gaelic. This is notable because the language was known to be in danger at that time and Morrison was involved in trying to revitalise it through language lessons[7] and the publishing of books such as Edmund Goodwin's First Lessons in Manx.[3] As Breesha Maddrell notes:[3]

"It is interesting to note that the number of poems, plays and prose in Standard English was double those in Anglo-Manx. These works were typically patriotic, or at least based on themes from Manx history. Manx Gaelic was written about more often than it actually appeared as a written language in the journal".

Also of note is the Foreword to the first issue of the journal, wherein Thomas Drury, former Bishop of the island, made explicit the distance of Mannin from the writings of Hall Caine, today considered to be the national novelist of the Isle of Man.[9] In contrast to the literary content of Mannin, Drury wrote of Caine's novels that "my soul revolts from such a travesty of Island life".[10]

There have been very few journals like Mannin on the Isle of Man. Perhaps closest in comparison are The Manx Notebook (1885–1887) edited by A.W. Moore[11] or Manninagh (1972–1973) edited by Mona Douglas, although they were each much shorter lived and had different focuses. In terms of literary content Mannin is the most significant and successful Manx journal.

References

- "The Manx Society, Annual Meeting", The Manx Quarterly No. 13, Vol. II

- A. W. Moore, in his presidential address to Yn Cheshaght Ghailckagh, 18 November 1899, quoted in "The Origin of the Manx Language Society", by Sophia Morrison, in the Isle of Man Examiner, 3 January 1914

- "Speaking from the Shadows: Sophia Morrison and the Manx Cultural Revival", Breesha Maddrell, Folklore, Vol. 113, No. 2 (Oct. 2002), pp. 215–236

- "Miss Sophia Morrison", in The Manx Quarterly No. 18, Vol. IV

- Sophia Morrison in a letter to her sister Lou in 1913, quoted in "Speaking from the Shadows: Sophia Morrison and the Manx Cultural Revival", Breesha Maddrell, Folklore, Vol. 113, No. 2 (Oct. 2002), pp. 215–236

- Mannin, Vol. V, No. 9

- "Sophia Morrison: In Memoriam", by P. W. Caine, in Mannin No. 9, May 1917

- "Should our National Legislature be Abolished?" by G. Fred Clucas, in Mannin No. 8, November 1916

- "Manx Literary Heritage" Archived 29 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine (accessed 20 May 2013)

- "Foreword" by Thomas Drury, in Mannin No 1, May 1913

- Selections from The Manx Notebook (accessed 20 May 2013)