Makoa

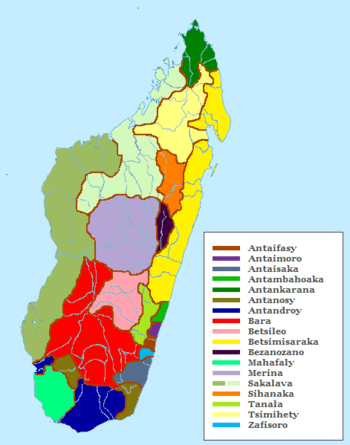

The Makoa (or Masombika) are an ethnic group in Madagascar descended from slaves traded through the major slave trading ports of northern Mozambique in an area mainly populated by the Makua people. They are among the last African diaspora communities in the world to issue from the slave trade. They are sometimes classified as a subgroup of the fishing peoples known as the Vezo (who are themselves a subset of the Sakalava people), although the Makoa maintain a distinct identity, one reinforced by their larger physical stature and historic employment as police officers by the French colonial administration.

The Makoa are descended from the Makua of Mozambique | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| c. ? | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Madagascar | |

| Languages | |

| Malagasy | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Makua people, Vezo people, Sakalava people, other Malagasy groups, Austronesian peoples |

Ethnic identity

The Makoa (called Masombika in the central highlands around the capital of Antananarivo) are an ethnic group in Madagascar descended from slaves traded through the major slave trading ports of northern Mozambique in an area mainly populated by the Makua people. They are one of the latest African diaspora groups in the world to be created as a result of the slave trade.[1] They are sometimes classified as a subgroup of the fishing peoples known as the Vezo (who are themselves a subset of the Sakalava people), although the Makoa maintain a distinct identity, one reinforced by their larger physical stature and historic employment as police officers by the French colonial administration.[2] The term Makoa is used today in Madagascar to refer not only to those who are believed descendants of Makua slaves, but also those who are very dark skinned, and those who are physically robust and powerful.[1]

History

Slave trading was a major source of wealth for Malagasy kings since at least the 16th century, when the first people from Mozambique arrived in the western part of Madagascar. They were not slaves, but rather migrants relocating to Madagascar to escape the slave trading that was then ravaging the eastern coast of Africa.[3] The largest slave trading ports in Mozambique were located in the north, an area traditionally populated by the Makua people, and while not all the slaves exported from these ports were Makua, the name came to be associated with slaves exported from the area. Madagascar was principally an exporter of slaves, however, as kings sold fellow Malagasy captured in conflicts and slave raids among enemy villages to European and Arab traders. In 1819, King Radama I, ruler of the Kingdom of Imerina that had come to dominate two thirds of the island of Madagascar from its capital at Antananarivo, capitulated to the entreaties of British diplomats to abolish the exportation of Malagasy slaves. The demand for slaves within Madagascar nonetheless remained strong, leading domestic slave traders to supplement those captured in Merina military expeditions to coastal provinces with others imported from Mozambique; clandestine importation of Makoa slaves increased dramatically over the course of the 19th century. The town of Maintirano, between Mahajanga and Morondava on the west coast, was a major hub of the illegal Mozambican slave trade. An estimated total of 650,000 Makoa slaves were exported from Mozambique to Madagascar in total, with as many as 30% of these being resold and exported to other western Indian Ocean islands.[1]

On 20 June 1877, Prime Minister Rainilaiarivony under Queen Ranavalona II passed a law liberating all Makoa slaves. An estimated 150,000 Makoa were emancipated in territories under the control of the Kingdom of Imerina; in other areas of the west coast beyond Merina administrative reach, the illegal slave trade persisted. The town of Morondava, under Merina administration, enforced the liberation of Makoa slaves, who grouped together to form their own neighborhoods within the city and established villages around its periphery. Makoa slaves from territory outside Merina control who managed to escape from their masters fled to Morondava to rejoin their free counterparts. Many joined the Norwegian Lutheran Mission that was active in Morondava in the late 19th century. In the 1880s, a number of Makoa solicited the aid of the Norwegian missionaries to help repatriate them to Mozambique. Over thirty years many Makoa in Morondava organized to return home, whether by building boats and rafts or by raising funds for passage on a ship. Norwegian records indicate that at least a few were successful in returning to Africa. Importation of Makoa slaves continued along portions of the west coast beyond Merina reach until the French colonized Madagascar in 1896 and outlawed all forms of slavery on the island.[1]

Throughout the colonial period, life in Makoa villages reflected strong and enduring ties to the traditions left behind in Mozambique: language, dance, music, food, storytelling and other cultural features were in evidence. Inhabitants of the villages crafted furniture, jewelry, utensils and musical instruments (particularly including drums) of the types used in Mozambique. Certain Makoa cultural practices were adopted by the neighboring Sakalava people,[1] including facial and body tattooing. Today, Makoa villages and neighborhoods are large and preserve a distinct identity relative to the surrounding communities, although most of the cultural practices have been deliberately abandoned or forgotten.[1]

Society

Within Makoa society, a three level caste system emerged to replicate that predominant in larger Malagasy society. A slave master would typically designate a leader of the Makoa, who took the title ampanjaka (king), as well as higher status slaves and lower status ones.[3]

Culture

Language

The Makoa speak a dialect of the Malagasy language, which is a branch of the Malayo-Polynesian language group derived from the Barito languages, spoken in southern Borneo. Historically they spoke Emakhuwa, the language spoken in northern Mozambique; church hymns and portions of the Bible were translated to Emakhuwa by Makoa Lutheran converts. There are several known Emakhuwa language documents written by Makoa in Madagascar that were carefully preserved by family and community members. Today, no living Makoa in Madagascar continue to speak this language as their mother tongue.[1]

Dance and music

The rap group Makoa claims to valorize an "Afro-Malagasy" identity associated with the Makoa people. Although the members of the group are not themselves Makoa by ethnicity, the popularity of the group and its inclusive message has contributed to rehabilitating the image of the Makoa in the popular imagination.[1]

Notes

- Boyer-Rossol, Klara (2 July 2014). "Réinvestir le sacré: Musiques, paroles et rites chez les anciens captifs déportés de l'Afrique orientale à Madagascar XIXe-XXe siècles" (in French). Africultures.com. Retrieved 27 September 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bradt & Austin 2007, p. 27.

- Rakotomalala, Malanjaona; Razafimbelo, Celestin (1985). "Le problème d'intégration sociale chez les Makoa de l'Antsihanaka" (PDF). Omaly sy Anio (in French). 21-22 (1): 93–113.

Bibliography

- Bradt, Hilary; Austin, Daniel (2007). Madagascar (9th ed.). Guilford, CT: The Globe Pequot Press Inc. pp. 113–115. ISBN 1-84162-197-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)