Lynx (web browser)

Lynx is a customizable text-based web browser for use on cursor-addressable character cell terminals.[6][7] As of 2020, it is the oldest web browser still in general use and active development,[8] having started in 1992.

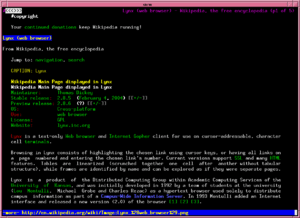

An older version of this article displayed in Lynx | |

| Original author(s) | Lou Montulli, Michael Grobe, Charles Rezac |

|---|---|

| Developer(s) | Thomas Dickey |

| Initial release | 1992 |

| Stable release(s) [±] | |

| 2.8.9rel.1[1][2] (8 July 2018) [±] | |

| Preview release(s) [±] | |

| 2.9.0dev.5 (27 February 2020[3]) [±] | |

| Repository | |

| Written in | ISO C |

| Engine | fork of libwww |

| Operating system | Unix-like,[4] DOS, Windows[5] |

| Available in | English |

| Type | Text-based web browser |

| License | GNU GPLv2 |

| Website | invisible-island |

History

Lynx was a product of the Distributed Computing Group within Academic Computing Services of the University of Kansas,[9][10] and was initially developed in 1992 by a team of students and staff at the university (Lou Montulli, Michael Grobe and Charles Rezac) as a hypertext browser used solely to distribute campus information as part of a Campus-Wide Information Server and for browsing the Gopher space.[11] Beta availability was announced to Usenet on 22 July 1992.[12] In 1993, Montulli added an Internet interface and released a new version (2.0) of the browser.[13][14]

As of July 2007 the support of communication protocols in Lynx is implemented using a version of libwww,[15] forked from the library's code base in 1996.[16] The supported protocols include Gopher, HTTP, HTTPS, FTP, NNTP and WAIS.[7][17] Support for NNTP was added to libwww from ongoing Lynx development in 1994.[18] Support for HTTPS was added to Lynx's fork of libwww later, initially as patches due to concerns about encryption.[19]

Garrett Blythe created DosLynx in April 1994[20] and later joined the Lynx effort as well. Foteos Macrides ported much of Lynx to VMS and maintained it for a time. In 1995, Lynx was released under the GNU General Public License, and is now maintained by a group of volunteers led by Thomas Dickey.[21]

Features

Browsing in Lynx consists of highlighting the chosen link using cursor keys, or having all links on a page numbered and entering the chosen link's number.[22] Current versions support SSL[7] and many HTML features. Tables are formatted using spaces, while frames are identified by name and can be explored as if they were separate pages. Lynx is not inherently able to display various types of non-text content on the web, such as images and video,[6] but it can launch external programs to handle it, such as an image viewer or a video player.[22]

Unlike most web browsers, Lynx does not support JavaScript or Adobe Flash,[23] which some websites require to work correctly.

The speed benefits of text-only browsing are most apparent when using low bandwidth internet connections, or older computer hardware that may be slow to render image-heavy content.

Privacy

Because Lynx does not support graphics, web bugs that track user information are not fetched; therefore, web pages can be read without the privacy concerns of graphic web browsers.[10] However, Lynx does support HTTP cookies,[6] which can also be used to track user information. Lynx therefore supports cookie whitelisting and blacklisting, or alternatively cookie support can be disabled permanently.[22]

As with conventional browsers, Lynx also supports browsing histories and page caching,[24] both of which can raise privacy concerns.[25]

Configurability

Lynx accepts configuration options from either command-line options or configuration files. There are 142 command line options according to its help message. The template configuration file lynx.cfg lists 233 configurable features. There is some overlap between the two, although there are command-line options such as -restrict which are not matched in lynx.cfg. In addition to pre-set options by command-line and configuration file, Lynx's behavior can be adjusted at runtime using its options menu. Again, there is some overlap between the settings. Lynx implements many of these runtime optional features, optionally (controlled through a setting in the configuration file) allowing the choices to be saved to a separate writable configuration file. The reason for restricting the options which can be saved originated in a usage of Lynx which was more common in the mid-1990s, i.e., using Lynx itself as a front-end application to the Internet accessed by dial-in connections.[26][27][22]

Accessibility

Because of its refreshable braille display and text-to-speech–friendly interface, Lynx can be used for internet access by visually impaired users.[28][11][17] As Lynx substitutes images, frames and other non-textual content with the text from alt, name and title HTML attributes[29] and allows hiding the user interface elements,[30] the browser becomes specifically suitable for use with cost-effective general purpose screen reading software.[31][32][33] A version of Lynx specifically enhanced for use with screen readers on Windows was developed at Indian Institute of Technology Madras.[34]

Remote access

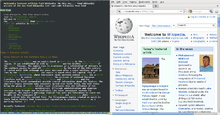

Lynx is also useful for accessing websites from a remotely connected system in which no graphical display is available.[35][36][37] Despite its text-only nature and age, it can still be used to effectively browse much of the modern web, including performing interactive tasks such as editing Wikipedia.[24][38][39]

Web design and robots

Since Lynx will take keystrokes from a text file, it is still very useful for automated data entry, web page navigation, and web scraping. Consequently, Lynx is used in some web crawlers. Web designers may use Lynx to determine the way in which search engines and web crawlers see the sites that they develop.[40][41][42] Online services that provide Lynx's view of a given web page are available.[43]

Lynx is also used to test websites' performance. As one can run the browser from different locations over remote access technologies like telnet and ssh, one can use Lynx to test the web site's connection performance from different geographical locations simultaneously.[38] Another possible web design application of the browser is quick checking of the site's links.[44]

Supported platforms

Lynx was originally designed for Unix-like operating systems, though it was ported to VMS soon after its public release and to other systems, including DOS, Microsoft Windows, Classic Mac OS and OS/2.[9] It was included in the default OpenBSD installation from OpenBSD 2.3 (May 1998)[45] to 5.5 (May 2014),[46] being in the main tree prior to July 2014,[47] subsequently being made available through the ports tree,[48] and can also be found in the repositories of most Linux distributions, as well as in the Homebrew[49] and Fink repositories for macOS.[39] Ports to BeOS, MINIX, QNX, AmigaOS[50] and OS/2[10] are also available.

The sources can be built on many platforms, e.g., mention is made of Google's Android operating system.[51]

See also

Notes

- Dickey, Thomas E. (8 July 2018). "Stable release". Retrieved 12 August 2018.

- Dickey, Thomas E. (8 July 2018). "Changes since Lynx 2.8 release". Retrieved 12 August 2018.

- "Changes since Lynx 2.8 release". lynx.invisible-island.net. 26 August 2019. Retrieved 4 September 2019.

- Nelson, H. (24 April 1999). "Lynx Installation Guide". lynx.invisible-island.net.

- Dickey, Thomas (11 September 2015). "Lynx2.8.8 [sic]". lynx.invisible-island.net.

- Rakitin 1997.

- Legan 2001.

- Davies 2012.

- Paciello 2000, pp. 154-155.

- Legan 2002.

- Bolso 2005.

- Montulli 1992.

- Stewart 2000.

- Nelson 2000.

- Kahan 1999.

- Dickey 2007.

- Seltzer 1995.

- Kahan 2002.

- Nestrud 2000.

- Buttles 1994.

- JUAN FERRER MARTÍNEZ (1 January 2015). UF1302 - Creación de páginas web con el lenguaje de marcas. Ediciones Paraninfo, S.A. pp. 73–. ISBN 978-84-283-9827-5.

- User's Guide.

- Wallen 2011.

- Senjen & Guthrey 1996, pp. 136-139.

- Timmer 2010.

- Help file.

- Configuration file.

- Paciello 2000, p. 157.

- RNIB 2011.

- Rosmaita 1996.

- Dixon 2004.

- Rosmaita.

- Sajka 1999.

- Achraya 2006.

- Wayner 2010.

- Chapman 2003.

- Killelea 2002, p. 9.

- Killelea 2002, pp. 60-61.

- Taylor 2005, pp. 225-227.

- King 2008, pp. 44-46.

- Bartlett 2006.

- Rognerud 2010, p. 187.

- Paciello 2000, p. 135.

- Killelea 2002, p. 178.

- OpenBSD23.

- OpenBSD55.

- de Raadt 2014.

- OpenBSDport.

- "Homebrew Formulae". Homebrew. Retrieved January 23, 2019.

- Marquardt 1995.

- "[APP] Compiled lynx binary for android - Shell or ADB". XDA Developers. Retrieved 2016-05-27.

References

- Paciello, Michael G. (January 2000). "Accessible Web Site Design". Web accessibility for people with disabilities. Focal Press. ISBN 978-1-929629-08-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rognerud, Jon (December 2010). Ultimate Guide to Search Engine Optimization: Drive Traffic, Boost Conversion Rates and Make Tons of Money (2nd ed.). Entrepreneur Press. ISBN 978-1-59918-392-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stewart, William (2000). "Web Browser History". The World's First Web Published Book. Living Internet.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- King, Andrew B. (December 2008). Website Optimization: Speed, Search Engine & Conversion Rate Secrets (revised ed.). O'Reilly Media. ISBN 978-0-596-51508-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Killelea, Patrick (2002). Web performance tuning (2 ed.). O'Reilly Media. ISBN 978-0-596-00172-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Taylor, Dave (2005). Learning UNIX for Mac OS X Tiger (4 ed.). O'Reilly Media. ISBN 978-0-596-00915-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Senjen, Rye; Guthrey, Jane (August 1996). The Internet for women. Spinifex Press. ISBN 978-1-875559-52-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Chapman, Greg (April 2003). "Text Based Web Browsing with LYNX". TechTrax. 2 (4). Archived from the original on 2012-01-17. Retrieved 2012-02-15.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dixon, Judith M. (December 2004). "Leveling The Road Ahead: Guidelines For The Creation Of WWW Pages Accessible To Blind and Visually Handicapped Users". Information Technology and Disabilities Journal. EASI. 2 (4). Retrieved 2012-02-15.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Seltzer, Richard (August 1995). "Maintaining Lynx to the Internet for People with Disabilities: A Call For Action". Information Technology and Disabilities Journal. EASI. 2 (3). ISSN 1073-5127. OCLC 222902674. Retrieved 2012-02-15.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Davies, Mike (2012). "What browsers other than IE and NN are there?". alt.html FAQ. Retrieved August 8, 2012.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wayner, Peter (2010-10-19). "Top 10 specialty Web browsers you may have missed". InfoWorld. p. 3. Retrieved 2010-10-28.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Legan, Dallas E. (2001). "Text-Mode Web Browsers for OS/2". The Southern California OS/2 User Group. Retrieved 2010-08-16.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Legan, Dallas E. (2002). "Lynx on OS/2: Straight Answers and Keen Tricks — Part 1 - Start Using the Lynx Browser". The Southern California OS/2 User Group. Retrieved 2010-08-16.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Marquardt, P. (1995). "The ALynx Homepage". owww.molgen.mpg.de. Retrieved 2020-01-30.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bartlett, Kynn (2006-09-29). "The Bad Browser: What to Do When Browsers Fail to Play Nice With Your CSS". InformIT. Retrieved 2012-02-15.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rosmaita, Gregory J. (1996-12-12). "BLYNX: Lynx Support Files Tailored for Blind and Visually Handicapped Users". BLYNX. Retrieved 2012-02-07.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Using access technology". RNIB. 2011-12-01. Retrieved 2012-02-08.

- Bolso, Erik Inge (2005-03-08). "2005 Text Mode Browser Roundup". Linux Journal. Retrieved 2010-08-05.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Timmer, John (2010-02-24). "Browser history hijack + social networks = lost anonymity". Ars Technica. Retrieved 2012-02-05.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rakitin, Jason (1997-10-27). "Review: Alternative Web browsers". Network World Fusion. Archived from the original on 2001-10-05.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wallen, Jack (2011-01-11). "10 Web browsers for the Linux operating system". TechRepublic. Retrieved 2012-02-12.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rosmaita, Gregory J. "An Introduction to Speech-Access Realities for Interested Sighted Internauts". BLYNX. Retrieved 2012-02-07.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kahan, José (1999-08-05). "Why Libwww?". World Wide Web Consortium. Retrieved 2010-06-15.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kahan, José (2002-06-07). "Change History of libwww". World Wide Web Consortium. Retrieved 2010-05-30.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Nelson, Lynn H. (2000-11-07). "Before the Web: the early development of History on-line" (PDF). Center for History and New Media. George Mason University. Retrieved 2008-02-03.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Montulli, Lou (1992-07-22). "Re: Unix and Hypertext". Newsgroup: alt.hypertext. Usenet: 1992Jul22.125801.41808@kuhub.cc.ukans.edu. Retrieved 2012-01-13.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sajka, Janina (1999-09-29). "Re: lynx-dev Licensing Lynx". lynx-dev (Mailing list).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Nestrud, Chris (2000-10-07). "Re: lynx, and https". blinux-list@redhat.com (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 2010-11-02.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dickey, Thomas E. (2007-07-02). "Re: [Lynx-dev] using fresher libwww?". lynx-dev@gnu.org (Mailing list).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- de Raadt, Theo (2014-07-15). "CVS: cvs.openbsd.org: src". source-changes@cvs.openbsd (Mailing list). OpenBSD. Retrieved 2014-07-16.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "lynx(1) man page". OpenBSD 2.3. 1998-05-19. Retrieved 2015-01-19.

- "lynx(1) man page". OpenBSD 5.5. 2014-05-01. Retrieved 2015-01-19.

- "www/lynx". OpenBSD ports. Retrieved 2015-01-19.

- Buttles, Wayne (1994). "DosLynx Beta Hype". FDISK.COM. Retrieved 2012-01-13.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Sound Enhanced Lynx". Acharya. IIT Madras. 17 August 2006. Archived from the original on 1 October 2006. Retrieved 7 February 2012.

- Lynx Developers Group. "Lynx User's Guide". Official website. Retrieved 2017-04-12.

- Lynx Developers Group. "Lynx 2.8.7 Help-File". Lynx official website. Retrieved 2017-04-12.

- Lynx Developers Group. "Configuration File". Lynx official website. Retrieved 2017-04-12.