Lynne Frederick

Lynne Maria Frederick (25 July 1954 – 27 April 1994) was a British actress,[1] film producer, and fashion model known for her classic English rose beauty. In a diverse and promising career, spanning ten years, she made over thirty appearances in film and television.

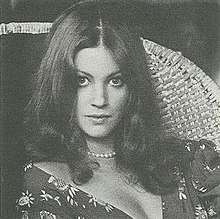

Lynne Frederick | |

|---|---|

Portrait by Terry Fincher, circa 1974 | |

| Born | Lynne Maria Frederick 25 July 1954 Hillingdon, Middlesex, England |

| Died | 27 April 1994 (aged 39) Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Resting place | Golders Green Crematorium |

| Other names | Lynne Sellers (legal married name) |

| Occupation |

|

| Years active |

|

| Known for | |

| Height | 5 ft 2 in (157 cm) |

| Spouse(s) | Barry Unger

( m. 1982; div. 1991) |

| Children | 1 |

For many years she was best remembered as the last wife and widow of Peter Sellers. Later, she began to establish a newfound cult following for her assorted collection of film work in Hollywood. Some of her better known performances include her roles in films such as Nicholas and Alexandra (1971), The Amazing Mr. Blunden (1972), Henry VIII and His Six Wives (1972), and Voyage of the Damned (1976).

Other films of hers such as Vampire Circus (1971), Phase IV (1974), Four of the Apocalypse (1975), A Long Return (Largo retorno) (1975), and Schizo (1976) have all become underground hits or established a status as a cult film in their respective genres.

She was the first recipient of the award for Best New Coming Actress from the Evening Standard British Film Awards in 1973, for her breakout performances in Henry VIII and His Six Wives (1972) and The Amazing Mr. Blunden (1972). She is one of only eight actresses, and the youngest, to hold this title.

Early life

Frederick was born in Hillingdon, Middlesex, to Andrew Frederick (1914–1983) and Iris C. Frederick (née Sullivan, 1928–2006). Lynne's parents separated when she was two years old, and she was brought up by her single mother and maternal grandmother, Cecilia. Lynne never knew or met her father, and had no personal relationships or connections with his side of the family. Although her mother had good employment as a casting director for Thames Television, they had limited financial means, and often lived a frugal lifestyle.

Frederick was raised in an austere and modest environment at Market Harborough in Leicestershire. She occasionally faced social stigma due to her parents' divorce, and being raised by her single mother. She attended Notting Hill and Ealing High School in London.[2] Her original career choice was to become a schoolteacher of physics and mathematics.[3][2]

Career

1969–74: early roles

Frederick was first discovered at the age of 15 by Hungarian-American actor and film director Cornel Wilde, who was a friend and co-worker of her mother. Wilde had been looking for a young unknown actress to star in his film adaptation of the best selling post-apocalyptic science fiction novel The Death of Grass. Wilde first saw her when she came to work with her mother to pose for some test shots and was immediately smitten by her beauty, charisma, and bubbly personality. Despite no previous experience in theatre, films, or commercials, Wilde offered her the role without an audition.[4]

When No Blade of Grass (1970) was released, the film received mixed reviews from critics. Despite the lukewarm reception of the film, it made Frederick an overnight sensation, and her career skyrocketed. She became a teen idol among the British public in the early 1970s, achieving the success and popularity equivalent to that of Hayley Mills and Olivia Hussey.[5] She was regularly featured in newspaper articles and fashion magazines as a model and cover girl.[2] Her most notable spread was in the British Vogue in September 1971, where she was photographed by Patrick Lichfield. In addition, she also appeared in several television commercials for products that include Camay soap. Frederick then signed a cosmetics contract with Mennen, and became a spokesmodel for Protein 21 shampoo, starring in nationwide campaign print and television ads. A British national newspaper chose her as its "Face of 1971", and she was hailed as one of Hollywood's most promising newcomers.[6]

In 1971 she appeared in the biographical film Nicholas and Alexandra (1971), in which she played the Grand Duchess Tatiana Nikolaevna of Russia, second eldest daughter of Tsar Nicholas II. For the film's press tour, she toured Europe with her three co-stars Ania Marson, Candace Glendenning, and Fiona Fullerton. That same year, she auditioned for the role of Alice in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1972),[6] but lost the role to her friend and Nicholas and Alexandra co-star, Fiona Fullerton. She was also first runner-up for the role of Saint Clare of Assisi in the Franco Zeffirelli production of Brother Sun, Sister Moon (1972),[6] which ultimately went to Judi Bowker.

Her best-known appearance was in 1972 where she played Catherine Howard, in Henry VIII and His Six Wives. Her next role was in the 1972 family film The Amazing Mr. Blunden; in 1973, she won the Evening Standard British Film Award for Best New Actress. She continued to work in various film and television projects throughout 1973 and 1974 where she often was cast in the archetype of the girl next door, an ingénue, or a princess. Some of the shows she appeared on were Follyfoot, The Generation Game, and an adaptation of The Canterville Ghost where she first met David Niven, who became a lifelong friend.

Frederick's most prominent television role came in 1974 where she appeared on three episodes of the critically acclaimed and Emmy-winning series The Pallisers. The series featured a huge cast of prominent and rising British actors, including Anthony Andrews, of whom she played the love interest.

1975–77: adult stardom

Frederick landed a role in the Spanish romance film A Long Return (Largo retorno) (1975), where she also made her debut and only appearance singing on a film's soundtrack. She also appeared alongside Fabio Testi in Four of the Apocalypse as well as in the adventure film Cormack of the Mounties. She returned to playing a teen-aged character in the Spanish film El Vicio Y La Virtud (1975).

Frederick began 1976 with an appearance on a controversial episode of the BBC series Play for Today, "The Other Woman", in which she played a sexually enigmatic girl who falls for a lesbian artist played by Jane Lapotaire.[7][8] Later the same year, she delivered a critically acclaimed performance in the Oscar-nominated film, Voyage of the Damned (1976). She followed that with a leading role in a Pete Walker slasher horror film, Schizo (1976), a movie that became an underground hit in the horror film community.

Along with Frederick’s rising mainstream success as an actress, her modeling career was also taking off, and she soon emerged as a fashion trendsetter and glamour girl of the late 1970s. Her popularity expanded across Europe to Japan, and she became a frequent face in the Japanese magazine, Screen. For this entertainment magazine she was featured as a celebrity centerfold pin-up, and made the cover three times in the span of a year and a half. Frederick was also listed in several press and editorial publications as one of photographer Terry Fincher’s muses.[9][10]

By this point in her career, Frederick was earning over £4,000[11] (£25,016.34 in 2020) per week working on films alone, and was being represented by A-list Hollywood agents Hazel Malone Management and Dennis Selinger. In addition, she had reached the point where she no longer needed to go on auditions for roles, and was being sent stacks of scripts and lucrative film offers.

1978–80: career decline and blacklisting

Following her marriage to Peter Sellers, Frederick's career stalled for over a year while she tended him through poor health. This included supporting and looking after him on the sets of his films.[11] She attempted to make a career comeback in 1978, but the year long absence had cost Frederick her burgeoning stardom.[12][11]

Frederick campaigned and auditioned for several films. The role that she most desired, and spent a great deal of time lobbying herself for, was the leading role of Meggie Cleary in The Thorn Birds. Despite her lengthy and accomplished acting résumé, the producers decided they wanted a much bigger catch. Other roles she campaigned for included Cosette in the 1978 television adaptation of Les Misérables (1978), and Anne Sullivan in the television remake of The Miracle Worker (1979), none of which she received. She made her final onscreen appearance with her husband, Sellers, in the 1979 remake of The Prisoner of Zenda, which was a box-office and critical flop. Her final credit was as an executive producer on Sellers' last film The Fiendish Plot of Dr. Fu Manchu.

Following Sellers' death, controversial will, ongoing feuds with her stepchildren, and her short marriage to David Frost, Frederick became a figure of hate and ridicule in the press, media, and tabloids. Labelled as a “gold digger”[13] and a “professional wife”[13] she was consequently shunned and blacklisted from Hollywood.

Personal life

Later life

After being blacklisted and losing her acting career, Frederick lived a very narrow, private, and reclusive lifestyle. When she divorced Frost, she faced public embarrassment when it was reported that she became intoxicated at a formal restaurant and had to be escorted out. Following this incident, she fled from England to California and never returned to her homeland again. In later years she was known for being fiercely private. Subsequently, she refused to give interviews and distanced herself from the celebrity lifestyle.

After her divorce from her third husband, Barry Unger, Frederick lived in a Los Angeles mansion that was previously owned by Gary Cooper. As the years went, she struggled with alcoholism, seizures, and clinical depression. There were also rumours of half-hearted suicide attempts. Despite participating in numerous recovery treatments at hospitals and clinics, she was unable to rebuild her health. Weary after her years of public scorn and deteriorating health, she cloistered herself in her home for days at a time. This led to her mother Iris moving from England to California to live with Frederick to help care for her and her daughter, Cassie.

Frederick was the sole manager of Sellers' estate. She took such pride in being Sellers' wife that she legally changed her last name to Sellers. It has been reported that when she took part in group therapy sessions, she introduced herself as "Lynne Sellers, the wife of Peter Sellers".[14]

Marriages

Frederick's first marriage at age 22 was to Peter Sellers. They met at a Dennis Selinger dinner party in 1976 after Frederick had finished making Schizo (1976). Sellers first proposed to her two days after their first meeting, but she turned him down. They dated for a year before he proposed to her again. They eloped in Paris on February 18, 1977.

Contrary to popular belief, their marriage started well, and they were a popular red carpet couple among the British public. Writer Stephen Bach said of their relationship, “I noticed as he [Peter Sellers] rose, that not once in the long talkative afternoon had he let go of Lynne’s hand, nor had she moved away. She transfused him simultaneously with calm and energy, and the hand he clung to was less a hand than a lifeline”.[15] He also added that he believed that Lynne had a unique ability to calm Sellers' manic moods; “the atmosphere was uneasy only until Lynne Frederick came into the room, exuding an aura of calm that somehow enveloped us all like an Alpine fragrance. She was only in her mid-twenties, but instantly observable as the mature center around which the household revolved, an emotional anchor that looked like a daffodil.”[15] British actor, David Niven, who was a friend to both Sellers and Frederick, had credited Peter’s happiness to Lynne being a devoted and loving wife.[16]

Their marriage went downhill as Sellers' ill health and other personal problems got increasingly worse, and Frederick forfeited her growing and lucrative acting career to care for him. Seller’s biographer, Ed Sikov, claimed that Frederick was offered a lucrative five-month television job in Moscow, but Sellers made her turn it down so that he wouldn't be left alone.[15]

The tension between them increased after the box-office and critical failure of The Prisoner of Zenda (1979), followed by negative tabloid reports of rumours of drug use, infidelity, domestic abuse, and other alleged lurid conflicts. Despite the struggles, Frederick stood by Sellers and cared for him as his health continually declined and he became more temperamental. Although they separated a number of times, they always came back together.

Sellers was reportedly in the process of excluding her from his will a week before he died of a heart attack on 24 July 1980, the day before her 26th birthday. The planned changes to the will not having been finalised, she inherited almost his entire estate, worth an estimated £4.5 million (£19.4 million today), and his children received £800 each (£3,456 today).[17][18] Despite appeals from a number of Sellers' friends to make a fair settlement to the children, Frederick refused to give her stepchildren anything due to their rocky relationship with her and Peter. After Sellers' death, her stepson, Michael Sellers, published an exposé memoir on his relationship with his father, P.S. I Love You: An Intimate Portrait of Peter Sellers. In the book he accused Frederick of being a deceitful, cunning, and narcissistic fraud who only married his father for his money.[19] He also made allegations that Frederick had cheated his sisters and him out of their inheritance by intentionally manipulating their father to alter the will in her favour.[19] This led to the press vilifying and labeling her as a "gold digger".[13]

She briefly married David Frost (on 25 January 1981), and her supposed eagerness to remarry so quickly after Sellers' death caused a loss of dignity in the public eye, and was one of the major factors in her blacklisting. Frederick divorced Frost after 17 months. During the course of their marriage, she suffered a miscarriage in March 1982.

In December 1982, she married California surgeon and heart specialist Dr. Barry Unger with whom she bore her only child, Cassie Cecilia Unger (born 1983); they divorced in 1991.[20]

Relationships

Frederick, who never met her biological father, regarded actor David Niven as her adopted father figure. They first met while filming the television film adaptation of The Canterville Ghost (1974). They remained close friends over the years until Niven's death in 1983, which occurred just eight weeks after the birth of her daughter. As a child, she was very close with her mother, Iris, and grandmother, Cecilia, but was estranged from both of them during the course of her marriage to Sellers. Iris said of her daughter’s marriage: “How could my daughter marry someone like Peter Sellers with his track record? The marriage is doomed from the start. My own marriage ended unhappily when Lynne was two. I tried to compensate for her having no father by devoting all the time I wasn’t working to her. Perhaps if I had married again she wouldn’t have gone on choosing men twice her age as boyfriends - looking for a father figure I suppose“.[19]

Frederick’s relationship with her stepchildren (Michael Sellers, Sarah Sellers, and Victoria Sellers) was, like Peter’s relationship with them, distant and often strained. When Lynne began her relationship with Peter, she made efforts to establish a friendly connection with them. Sarah recalled of Lynne, “she seemed quite nice to begin with. I actually told dad that I thought she was a bit stupid. But she came across as very bubbly, friendly, warm and interested. But once they got married things definitely changed”.[15] Michael Sellers shared his thoughts of Frederick in his exposé memoir where he said “my first impression of Lynne didn’t do much to alter my views. She was not exactly my idea of sweetness and light. It didn’t concern me that she lacked the good looks of dad’s past wives and girlfriends, but those innocent eyes, certainly her strongest feature, didn’t deceive me”.[19] Michael Sellers also bluntly acknowledged his intentional hostility and lack of respect towards Lynne when they first met: “I’m afraid we weren’t very kind in our judgement of Lynne. Sarah thought she wasn’t too bright. But our views didn’t really count for much. Because whatever our opinions, they would be of purely academic interest”.[19] Months after Frederick's death in 1994, Victoria remarked “I feel now that she’s in hell - I don’t know but that makes me feel better.”[21]

When she made the film Nicholas and Alexandra (1971), the director, Franklin J. Schaffner, arranged for Lynne and her co-stars (Michael Jayston, Janet Suzman, Roderick Noble, Ania Marson, Candace Glendenning, and Fiona Fullerton) to live together as a family during the nine month production period, as to add more authenticity to their performances. During this time she developed a close friendship with her co-star Fiona Fullerton (who played her younger sister in the film). They remained good friends for several years.

One of Frederick’s closest friends was Mauritian actress, Françoise Pascal. The two first met when they co-starred on a 1972 episode of the television anthology series, BBC Play of the Month, and quickly became “firm friends”.[22] Pascal recalled that they remained friends for several years before regretfully losing touch after Frederick married Sellers in 1977. In April 2020, a few weeks before the 26th anniversary of Frederick's death, Pascal tweeted a photo of herself and Frederick, with the caption "I think of her very often! Always had that fresh baby face! RIP Lynne! Xxx".[23]

In 2018, Judy Matheson revealed that she had worked with Frederick in the early 1970s. They were slated to appear in a film together that was to be shot in the Netherlands, with John Hamil, Robert Coleby, and Nina Francis. Because Frederick was young and a relative newcomer to filmmaking at the time, Matheson (who was a few years older and had industry experience) was asked to be Lynne's chaperone for the trip (as Lynne's mother was unavailable). They spent about three weeks lodged together in a hotel room before production on the film was prematurely closed due to financial withdrawals. Matheson stated that she enjoyed Frederick's company, and that they managed to have fun together despite the production struggles. After returning to Great Britain, they corresponded for a while before gradually losing touch with each other.

During production of Four of the Apocalypse (1975), she was rumoured to have had a brief romance with her co-star Fabio Testi (who was having trouble in his relationship with actress Ursula Andress at the time). Naturally, this helped Testi and Frederick with their chemistry in the movie, and they were paired again for the film Cormack of the Mounties (1975). There has been much speculation about such a romance between Testi and Frederick, but it has not been confirmed.[24]

In her 2014 memoir I Said Yes to Everything, Lee Grant claimed that during production of the film Voyage of the Damned (1976) Frederick, then aged 21, engaged in an affair with Sam Wanamaker, who was 35 years Frederick’s senior and married to Charlotte Holland at the time. Grant also stated that she witnessed all the men on set, including the film's director Stuart Rosenberg, make salacious passes at Frederick, all of which she rejected.[25]

Julie Andrews stated in her 2019 autobiography Home Work: A Memoir of My Hollywood Years that she suspected her husband Blake Edwards was having an affair with Lynne (who was married to Sellers at the time) during production of Revenge of the Pink Panther (1978).[26] When Andrews confronted Blake about the "flirtations" between him and Frederick, Julie asked him point-blank which he preferred: staying married or continuing this flirtation.[27] After this confrontation, Blake ceased all alleged flirtations with Frederick. She later had a fall-out with Edwards and Andrews after successfully suing them for their involvement with the film Trail of the Pink Panther (1982), claiming that it insulted Sellers' memory.[28] She never spoke to them again.

British journalist Nigel Dempster claimed that she had a four-year relationship with a man named Julian Posner, who ran the Curzon House Club casino in Mayfair. Dempster claims that Posner was three decades Frederick's senior and that this long-term relationship began when she was in her late teens and ended in her early 20s (before her meeting Sellers).[13] However this claim has been disputed by many.

Political views and beliefs

In a 1975 interview with Men Only, Frederick discussed that she "partially agreed" with Women's Lib. Adding "I agree with the fact that women should have equal rights", but adding that she also believed in some old fashioned gender roles. "I agree that there are certain things that men are designed to do; just as there are things women are designed to do."[29]

She was a supporter of Margaret Thatcher, calling her a "very capable woman", and stating that "I think women are just as capable of ruling people and looking after our affairs as men are. Sometimes possibly better because women have a level of sensibility and sensitivity as well, which possibly men don't sometimes."[29]

Frederick was known for being a blunt and outspoken advocate for same sex relationships and LGBT rights during a time when it was considered highly taboo. Following her appearance on a controversial episode of the television series Play for Today, where she played a sexually fluid character and shared an onscreen kiss with her female co-star, Jane Lapotaire, she said "with homosexuality and lesbianism, I just don't think you can put a ban on it. I don't think you can say it's wrong. I think people should live how they want to live. I don't think it should be illegal."[29]

She was agnostic and briefly spoke on her religious beliefs when she was asked about the progressive Catholic priest's response to the pope's declaring premarital sex a sin. "I really agree with the other priests that it should have never been issued. I think that does put the Church back; I really do. I can say it because I'm not particularly religious. But I think people who are religious, I hope they would feel that it's not a step forward. I think premarital sex is a good idea. I think the worst thing that could possibly happen is to not have sex before you get married, then get married and find out it's dreadful."[29]

Philanthropy

Following the death of her first husband Peter Sellers, she became involved in donating to various heart charities. After her death, she left $250,000 to be split between the British Heart Foundation and the Middlesex Hospital in London as tribute to Sellers (who died of a heart attack). As a sign of gratitude, the Middlesex Hospital hung a plaque thanking both Sellers and Frederick for their generous contributions.

Trail of the Pink Panther (1982) lawsuit

Shortly after the release of Trail of the Pink Panther (1982), Frederick filed suit against MGM, United Artists, and film director Blake Edwards for 3 million dollars in damages and to block the films distribution. She claimed that the film tarnished Peter Sellers' reputation, and was made without authorization from his estate, which she had control over.[28]

In the London high court, the defence argued that the film was meant to be a tribute to Sellers, but Frederick stated “It was an appalling film: Not a tribute to my husband but an insult to his memory.”[30] Her chief objection was that her late husband had specifically prohibited the use of outtakes from earlier Pink Panther films in his lifetime, and that his estate should have had the right to control the use of outtakes after his death. The idea of using outtakes in future films was presented in Sellers' lifetime when Edwards had shot and edited a three-hour version of The Pink Panther Strikes Again (1976). However United Artists objected to this long version and the film was trimmed from three hours to an hour and a half.[14]

After Sellers' death in 1980, UA, wanting to cash in on the continuation of the series, elected Edwards to construct a new film from outtakes and deleted scenes from the five previous Pink Panther movies featuring Sellers. A handful of new material involving other actors was filmed for this movie. Some of the older material dated as far back as nineteen years before this movie was made, to 1963. The negligence in continuity was evident in many scenes, and was subjected to heavy mockery from film critics.[31]

In 1985 Judge Charles Hobhouse ruled in favour of Frederick, awarding her $1 million dollars, but dismissed her request to ban the film.[30] Despite her noble intentions to protect Sellers' legacy, the press further sneered at her.[31] Frederick herself stated “I hope this proves that I’m not a gold digger! I’ve risked my entire fortune and the financial future of my daughter to protect Peter's reputation.”[31] After the lawsuit, Frederick continued to guard Sellers' films and went to great lengths to make sure each one was handled with respect and dignity.[15]

Death

On 27 April 1994, Frederick was found dead by her mother in her West Los Angeles home, aged 39. A post-mortem failed to determine the cause of death, but ruled out foul play and suicide.[32] The lack of knowledge surrounding the circumstances of her death led to the press declaring her death to be from the effects of alcoholism. Her remains were cremated at Golders Green Crematorium in London, and her ashes were interred with the ashes of her first husband, Peter Sellers.

In a 1995 interview with Hello magazine, her mother, Iris, claimed that Lynne died from a seizure in her sleep. She also denied accusations that her daughter had a drug or alcohol problem.[33]

“There is absolutely no truth in any of the stories I have read about Lynne’s death. I never saw Lynne taking cocaine. She liked a glass of wine, but so do most people and she was no more an alcoholic than the next person. The autopsy report was quite clear, her death was by natural causes. Lynne died of a seizure in her sleep. For the record, the coroner found no evidence that Lynne had been taking drugs.”

Legacy

In the years after her death, Frederick's legacy remained poisoned and she seldom was talked about in favourable terms. In the 2004 book The Life and Death of Peter Sellers, Roger Lewis claimed that "there is yet to find a single person to say a good thing about Lynne".[14] British journalist Nigel Dempster had a profound dislike for Frederick and referred to her as an “avaricious and cunning man-eater”.[13] Other people who have voiced unfavorable views of Lynne included Spike Milligan, Britt Ekland[34], Sir Rodger Moore[35], Wendy Richard[36], and Simon Williams.

She received minimal attention in the 2004 movie adaptation of Lewis's book where she was portrayed by British actress Emilia Fox. All scenes featuring Fox's portrayal of Frederick were deleted from the final cut of the film, but included in the supplemental features of the film's DVD release. On portraying Frederick, Fox stated "I had thought very carefully about playing Lynne. I wanted to represent her in a way that I thought was fair - which was a very young girl being taken up in this world of laughter and light, and then finding out the reality. Peter Sellers was completely obsessed by work and it's very difficult to live with someone like that."[37]

Over time, views towards her image gradually shifted, and she soon gained a cult following[38] through her films, and has been described as one of the most promising, talented, beautiful, and ascending young British actresses of the 1970s.[39] Many credit the negative events in her life (the loss of her acting career, blacklisting in Hollywood, and untimely death) to her marriage to Sellers. Even Roger Lewis, who was blunt about his disdain for Frederick, admitted that "of all of Sellers's wives, Lynne Frederick was the most poorly treated".[40] One of the first people to advocate for Lynne was American author, Ed Sikov, in the 2002 book, Mr. Strangelove: A Biography of Peter Sellers: "Lynne Frederick deserves a bit of compassion herself in retrospect. It was the helpless Peter she nursed, the dependent and infantile creature of impulse and consequent contradiction. Patiently she ministered him".[15] Other people who have defended or spoke fondly of Lynne over the years include Judy Matheson[41][42], Françoise Pascal[23], John Moulder-Brown[43], Mark Burns, Fabio Testi, Ty Jeffries, Lionel Jeffries, David Niven[16], and Graham Crowden.

There has been continued belief that Frederick would have achieved greater career success had it not been for her marriage to Sellers and untimely death.[6] It’s even been theorized that she had the potential to attain stardom equivalent to that of Helen Mirren, Judi Dench, and Julie Walters.[6]

In 1982, Frederick's screen appearance as Catherine Howard from the film Henry VIII and His Six Wives (1972), was used on the cover art for the 1982 novel The Dark Rose by Cynthia Harrod-Eagles.

For her work in horror films, Frederick has garnered significant popularity as a scream queen.[38]

The Times obituary for Frederick called her the "Olivia Hussey of her day”.[44]

Filmography

Film

| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1970 | No Blade of Grass | Mary Custance | film debut |

| 1971 | Nicholas and Alexandra | Grand Duchess Tatiana Nikolaevna | |

| 1971 | Vampire Circus | Dora Miller | |

| 1972 | Henry VIII and His Six Wives | Catherine Howard | Evening Standard British Film Award for Best New Coming Actress |

| 1972 | The Amazing Mr. Blunden | Lucy Allen | Evening Standard British Film Award for Best New Coming Actress |

| 1973 | Keep an Eye on Denise | Denise | television film |

| 1974 | The Lady from the Sea | Hilde | television film |

| 1974 | Phase IV | Kendra Eldridge | |

| 1974 | The Canterville Ghost | Virginia Otis | television film |

| 1975 | Four of the Apocalypse | Emmanuella "Bunny" O'Neill | |

| 1975 | Cormack of the Mounties | Elizabeth | |

| 1975 | A Long Return | Anna Ortega | |

| 1975 | The Vice and Virtue | Rosa | |

| 1976 | Schizo | Samantha Grey/Jean | |

| 1976 | Voyage of the Damned | Anna Rosen | |

| 1977 | Hazlitt in Love | Sarah Walker | television film |

| 1979 | The Prisoner of Zenda | Princess Flavia | final film role |

Television

| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1971 | Now, Take My Wife | Jenny Love | Series 1, Episode 1: "Just Harry and Me" |

| 1971 | Comedy Playhouse | Jenny Love | Series 11, Episode 1: "Just Harry and Me" |

| 1971 | Fathers and Sons | Dunyasha | Series 1, Episode 1 |

| 1972 | BBC Play of the Month | Nellie Ewell | Series 7, Episode 5: "Summer and Smoke"‡ |

| 1972 | Softly, Softly: Taskforce | Judith “Judy” Oram | Series 3, Episode 17: "Anywhere in the Wide World" |

| 1972 | Opportunity Knocks | Never Again | Series 12, Episode 25: "The Script Writers Chart Show" |

| 1973 | No Exit | Abigail "Abby" | Series 1, Episode 3: "A Man's Fair Share of Days" |

| 1973 | Away from It All | Vinca | Series 1, Episode 1: "The Ripening Seed" |

| 1973 | Follyfoot | Tina | Series 3, Episode 8: "The Bridge Builder", Episode 9: "Uncle Joe" |

| 1973 | Wessex Tales | Rosa Harlborough | Series 1, Episode 1: "A Tragedy of Two Ambitions" |

| 1973 | The Generation Game | Cinderella | Series 3, Episode 17: "1973 Christmas Special" |

| 1974 | Masquerade | Natalie Fieldman | Series 1, Episode 3: "Mizzen ab!" |

| 1974 | The Pallisers | Isabel Boncassen | Series 1, Episodes 24, 25, and 26 |

| 1976 | Play for Today | Nikolai “Nikki” | Series 6, Episode 11: "The Other Woman" |

| 1976 | Space: 1999 | Shermeen Williams | Series 2, Episode 15: "A Matter of Balance" |

‡ denotes lost film

Discography

Soundtrack appearances

| Title | Year | Album |

|---|---|---|

| "Today (Anna's Love Song)" | 1975 | A Long Return Soundtrack¤ |

| "Today (Anna's Love Song) (Reprise)" | ||

¤ denotes that the soundtrack/album never received an official release

Live performances

| Title | Year | Other artist(s) |

|---|---|---|

| "If You Were the Only Girl in the World"៛ | 1973 | Bruce Forsyth |

៛ Performed live 25 December 1973 on the BBC show The Generation Game

Awards and nominations

| Year | Association | Category | Nominated work | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1973 | Evening Standard British Film Awards | Best Newcomer - Actress | The Amazing Mr. Blunden (1972) and Henry VIII and His Six Wives (1972) | Won |

References

- Peter Noble (1974). British Film and Television Year Book. Cinema TV Today. p. 144.

- "School to stardom". The Sunday People. 23 January 1972.

- Davis, Clifford (31 October 1970). "The stars go to market". Daily Mirror.

- Watson, Albert (27 June 1970). "At 15, she's set for a film career". Aberdeen Evening Express: 12 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- "Autumn Bird". Daily Mirror: 7. 3 October 1970 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- Edwards, Jonathan (1 January 2020). "Lynne Frederick Remembered » We Are Cult". We Are Cult. Retrieved 3 January 2020.

- Farquhar, Author Simon (5 June 2017). "Savage Ms-Siah". Dreams Gathering Dust. Retrieved 21 February 2020.

- Isaacs, David (31 December 1975). "Another side of the triangle". Conventry Evening Telegraph: 17 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- "The Seven Ages of Lynne". Daily Mirror: 14–15. 15 January 1976 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- Hagerty, Bill (9 June 1976). "Shipmates on the voyage". Daily Mirror: 14 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- Walker, Alexander. (1981). Peter Sellers, the authorized biography. New York: Macmillan. ISBN 0-02-622960-9. OCLC 8034307.

- "Peter, you loved me, yet hurt me". Woman’s Own Magazine. November 1980.

- Dempster, Nigel (1998). Dempster's people : inside the world of the gossip's gossip. HarperCollins. p. 20. ISBN 0002570238.

- Lewis, Roger (1995). The life and death of Peter Sellers. Applause. ISBN 1557833575.

- Sikov, Ed. (2003) [2002]. Mr. Strangelove : a biography of Peter Sellers (1st pbk. ed.). New York: Hyperion. ISBN 0-7868-8581-5. OCLC 53929283.

- Fowler, Karin J. (1995). David Niven: A Bio-bibliography. London: Greenwood Press. p. 261. ISBN 978-0313280443.

- Richard Savill,The Telegraph: "Peter Sellers tried to cut fourth wife Lynne Frederick out of his £4.5 million will", 5 November 2009

- "Peter Sellers 'tried to change will' before he died". BBC News – Entertainment. BBC. 16 July 2010. Retrieved 19 July 2010.

- Sellers, Michael, 1954-2006. (1981). P.S.I love you : Peter Sellers, 1925-1980. Sellers, Sarah, 1957-, Sellers, Victoria, 1965-. London: Collins. ISBN 0-00-216649-6. OCLC 8132491.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "Obituary: Lynne Frederick". The Independent. 3 May 1994. Retrieved 15 August 2020.

- "Confessions of a spoilt little rich girl". Irish Independent Weekender. 16 July 1994.

- Pascal, Francoise (13 April 2020). "We both worked in a BBC Play of the month called Summer and Smoke, we became firm friends. Then she met Peter S and she told me she was marrying Peter. I was happy for both of them. We lost touch and the last time I spoke to her is when Peter died. Never saw her again". @fpascal. Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- Pascal, Francoise (13 April 2020). "I think of her very often! Always had that fresh baby face! RIP Lynne! Xxxpic.twitter.com/G7ckW91bgx". Twitter @fpascal. Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- "The Four of the Apocalypse... (1975) - Trivia - IMDb". Internet Movie Database.

- Grant, Lee (2014). I said yes to everything : a memoir (1st ed.). Plume. p. 302. ISBN 9780147516282.

- Andrews, Julie (15 October 2019). Home work : a memoir of my Hollywood years (First ed.). Hachette Book Group. pp. 241–245. ISBN 978-0316349253.

- Cutler, Jacqueline. "Julie Andrews new bio shows life was mostly spoonful of sugar, some bitter fruits". nydailynews.com. NY Daily News.

- Gentle, David (15 November 2016). On the tip of my tongue : questions, facts, curiosities and games of a quizzical nature (New & updated ed.). London. ISBN 978-1-4088-7133-1. OCLC 930017478.

- Robbins, Fred (1975). "Men Only Interview with Lynne Frederick". Men Only Magazine: 18–22.

- "PETER SELLERS' WIDOW WINS 'PANTHER' SUIT". Los Angeles Times. 25 May 1985. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- Upton, Julian. (2004). Fallen stars : tragic lives and lost careers. Manchester, U.K.: Headpress/Critical Vision. ISBN 1-900486-38-5. OCLC 56449666.

- Obituary, nytimes.com, 2 May 1994.

- Knapp, Mike (18 March 1995). "Talking For The First Time A Year After The Actress' Death". Hello Magazine: 18–23.

- Ekland, Britt, 1942- (1981) [1980]. True Britt. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall. ISBN 0-13-931089-4. OCLC 7197812.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Moore, Roger, 1927-2017,. Last man standing : tales from Tinseltown. Owen, Gareth, 1936-. London. ISBN 978-1-78243-207-4. OCLC 883464880.CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Richard, Wendy, 1943-2009. (2000). Wendy Richard-- no 's' : my life story. Wiggins, Lizzie. London: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-7432-1870-1. OCLC 123106387.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Hoggard, Liz. "I felt like an awful old harlot". The Guardian. The Observer.

- Rodriguez, Percy (25 July 2019). "Lynne Frederick, The Legacy of a Scream Queen, 65th Birthday Tribute". Spooky Isles.

- "A Budding Rose – Remembering Lynne Frederick (1954 – 1994)". Tina Amount’s Eyes. 6 November 2013.

- Lewis, Roger (1995). The Life and Death of Peter Sellers. UK: Applause. ISBN 1557833575.

- Matheson, Judy (2 February 2018). "Ah, knew her. She was totally lovely. We were once marooned in a shared hotel room in The Hague for 3 weeks. Hardly the stuff of stardom, as we moaned at the time..." Twitter @judyjarvis. Retrieved 15 August 2020.

- Matheson, Judy (3 February 2018). "Early 70s. We were waiting for producers to 'produce' the money to make a film that never materialised. We had fun though, but I can't remember any deep convos. Lynne was delightful company". Twitter @judyjarvis. Retrieved 15 August 2020.

- "Interview: John Moulder-Brown By Professor Kinema". From Zombos' Closet. Retrieved 15 August 2020.

- "Lynne Frederick (1954-1994) Obituary". The Times. 2 May 1994.