Ludwig Rabus

Ludwig Rabus (also Rab or Günzer) (10 October 1523 – 22 July 1592) was a German Lutheran theologian and Protestant reformer.

Life

He was born in Memmingen, in poor circumstances. He went to Strasbourg, where he was supported by the preacher Matthäus Zell and his wife Katharina. In 1538 Rabus became a student at University of Tübingen, and graduated M.A. in 1543.

In the following years Rabus became Zell's assistant, made a reputation as a preachers, and in 1548 was Zell's successor. The Augsburg Interim meant he lost his post, but he remained in Strasbourg. In 1552 he became head of the Collegium Wilhelmitanum and teacher at the High School; in 1553 together with Jacob Andreae he was awarded a Tübingen doctorate.

When the Strasbourg council favoured Johannes Marbach, Rabus left the city, where he was regarded as something of a fanatic, and went as minister and dean to Ulm, where he worked for 34 years. In the controversy around Kaspar Schwenckfeld he wrote against Katharina Zell, who defended herself; what had been a long-running private disagreement about her husband's legacy became a public quarrel.[1]

In Ulm Rabus standardised teaching, held inspections, introduced liturgical books, and supported Andreae in his efforts towards the Swabian Concord. He died there.

Works

Rabus began to work on a selective Protestant martyrology in the late 1540s, as the Interim began to affect churches in his region. A Latin version appeared in 1552.[2]

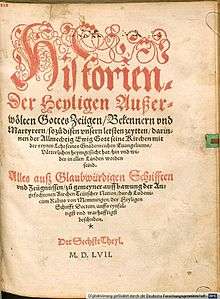

The German Historien der Heyligen appeared in six volumes (completed 1557), published at Strasbourg by Samuel Emmel. It is framed as a universal history. The first volume begins with Abel and discusses biblical stories and martyrs of the Early Christian Church; it uses Eusebius of Caesarea as a source. In the following five books around 70 martyrologies are given.[3] He dedicated his book of martyrology to the Strasbourg council; as well as to Christoph, Duke of Württemberg.[4]

References

Notes

- Elsie Anne McKee, Church Mother: the writings of a Protestant reformer in sixteenth-century Germany (2006), p. 179; Google Books.

- Robert Kolb, For All the Saints: changing perceptions of martyrdom and sainthood in the Lutheran Reformation (1987), p. 45–6.

- John N. King, Foxe's Book of Martyrs and Early Modern Print Culture (2006), p. 41; Google Books.

- Kolb, p. 47; Google Books.