Lucy Addison

Lucy Addison (December 8, 1861 in Upperville, Virginia – November 13, 1937 in Washington, D.C.) was an African-American school teacher and principal.[1][2] In 2011 Addison was honored as one of the Library of Virginia's "Virginia Women in History" for her contributions to education.[3]

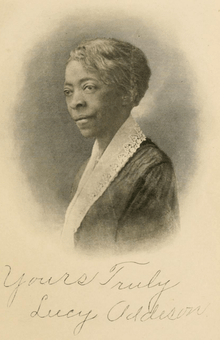

Lucy Addison | |

|---|---|

Portrait of Addison from History of the American Negro and his institutions, published 1917 | |

| Born | December 8, 1861 |

| Died | November 13, 1937 (aged 75) Washington, D.C. |

| Occupation | Teacher, principal |

Personal life

Addison was born on December 8, 1861 in Upperville, Virginia to Charles Addison and Elizabeth Anderson Addison, both of whom were slaves. She was the third child born to the couple and the second daughter.[4] After her family was emancipated Lucy's father purchased farm land in Fauquier County and Addison began attending school. She later traveled to Philadelphia to attend the Institute for Colored Youth, and graduated with a teaching degree in 1882. Addison kept her skills current by attending continuing education classes at schools, including Howard University and the University of Pennsylvania. She later served in several supervisory positions, including as a member of the board of trustees for the Burrell Memorial Hospital.[4]

Education work

Shortly after receiving her degree, Addison returned to Virginia and began teaching in Loudoun County, Virginia. In 1886, she moved to Roanoke, Virginia to teach at the First Ward Colored School. The following year Addison began serving as an interim head following the death of the school's principal. She continued as such until 1888, when a new school was built and a male principal hired.[4] Addison then served for more than a decade as both a teacher and an assistant principal for the school.[4]

In 1917 Addison was hired to serve as the principal for the Harrison School, a school for African-Americans.[2][5] Although the school was only accredited to teach up to the eighth grade, Addison expanded the curriculum to include high school level classes while also continually lobbying Virginia State Board of Education for full accreditation. Her work came to fruition in 1924, when the Board granted the school full accreditation and the school graduated several students with a high school diploma.[4] Addison retired in 1927 and moved to Washington, D.C. to live with one of her sisters, but returned to Virginia for several occasions, including the naming of Roanoke's first public high school for African Americans in her honor.[4]

Death and legacy

Addison suffered from chronic nephritis and died in Washington, D.C. on November 13, 1937. She was buried in Columbian Harmony Cemetery. In 1970 her remains were re-interred when the cemetery was moved to Maryland to become part of National Harmony Memorial Park.[4]

Roanoke opened the Lucy Addison High School the year after Addison retired, and she traveled to Virginia to attend the opening ceremony.[4] In the 1970s the school was almost closed and turned into a vocational school, as Roanoke's desegregation plans proposed busing pupils into neighboring areas. However, U.S. District Judge Ted Dalton ordered the school remain open.[6] In 1973 the school was restructured[7] and became the Lucy Addison Junior High School,[8] which was later renamed the Lucy Addison Middle School.[9][10][11]

References

- Curtis, Nancy C. (1998). Black Heritage Sites: The South. New Press. pp. 307–308. ISBN 9781565844339.

- Loth, Calder (1995). Virginia Landmarks of Black History. University of Virginia Press. pp. 88–89. ISBN 9780813916019. Retrieved 13 March 2015.

- "Virginia Women in History: Lucy Addison". Library of Virginia. Retrieved 13 March 2015.

- Kneebone, John T. "Lucy Addison (1861–1937)". Encyclopedia Virginia/Dictionary of Virginia Biography. Retrieved 10 March 2015.

- Savage, Beth L. (1994). African American Historic Places. Wiley. pp. 45, 515. ISBN 9780471143451. Retrieved 13 March 2015.

- "Desegregation Plans In Roanoke Rejected". The Free Lance-Star. Aug 12, 1970. Retrieved 13 March 2015.

- http://trdudley.com/LAHS/

- Fifer, Jordan. "Principal guided Patrick Henry through tumultuous integration". Roanoke Times. Retrieved 13 March 2015.

- Poindexter, Joanne. "Deadline nears for inscriptions on the Lucy Addison High School Monument Wall". Roanoake Times. Retrieved 13 March 2015.

- "The Legacy of Miss Lucy Addison". Lucy Addison Middle School. Archived from the original on 13 March 2015. Retrieved 13 March 2015.

- Shareef, Reginald (1996). The Roanoke Valley's African American Heritage: A Pictorial History. Donning Company Publishers. pp. 13, 19, 27. ISBN 9780898659627. Retrieved 13 March 2015.

External links

- Biography at Encyclopedia Virginia

- Lucy Addison Middle School home page