Louis-Charles Le Vassor de La Touche

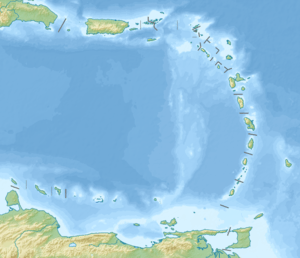

Louis-Charles Le Vassor de La Touche de Tréville (31 March 1709 – 14 April 1781), comte de La Touche, was a French naval general who was governor of Martinique and governor general of the Windward Islands.

Louis Charles Le Vassor de La Touche de Tréville, comte de La Touche | |

|---|---|

| Governor-general of the Windward Islands | |

| In office February 1761 – February 1762 | |

| Preceded by | François V de Beauharnais |

| Succeeded by | Robert, comte d'Argout |

| Governor of Martinique | |

| In office February 1761 – February 1762 | |

| Preceded by | François V de Beauharnais |

| Succeeded by | William Rufane |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 31 March 1709 Le Lamentin, Martinique, France |

| Died | 14 April 1781 (aged 72) Paris, France |

| Nationality | French |

| Occupation | Naval soldier |

Birth and family

Louis-Charles Le Vassor de La Touche was born on 31 March 1709 in Le Lamentin, Martinique.[1] His family had been established in Martinique since the middle of the 17th century, and was ennobled in 1706.[2] His grandfather was one of the leaders of the Gaoulé revolt in 1717.[3] His father was Charles Lambert Le Vassor de La Touche (1677–1737), a militia colonel, lieutenant general, captain general of the coastguard of Le Croisic. His mother was Marie Rose de Mallevaut (1684–1724).[1] One of his brothers was Charles Augustin Levassor de La Touche Tréville (1712–1788), who became a lieutenant general of naval armies.[2]

Early naval career (1726–1756)

La Touche joined the navy, and became a garde marine in 1726, and an enseigne de vaisseau (ensign) in 1733 . On 10 May 1741 he was promoted to lieutenant de vaisseau (ship-of-the-line lieutenant). In 1744 he was made a knight of the Order of Saint Louis.[2] In 1744 La Touche married Marie Madeleine Rose de Saint-Léguer de La Saussaye. Their son was Louis René (1745–1804), comte de La Touche-Tréville.[1] Louis-René became a vice-admiral and deputy for the nobility at the Estates General in 1789.[2]

In June-October 1746 La Touche served in the Duc d'Anville expedition as second lieutenant on the Northumberland. This was a large expedition that tried without success to retake Port Royal and Acadia in response to the capture of Louisbourg by the British in 1745. He also participated in the campaign of Chibouctou (now Halifax, Nova Scotia). This was a naval disaster in which numerous ships were lost and 8,000 men died, according to one source. The Duc d'Anville fell sick and died, and his replacement Constantine Louis d'Estourmel attempted suicide.[2]

On 17 May 1751 La Touche was promoted to capitaine de vaisseau (ship-of-the-line captain).[2] On 2 May 1752 he married Marie-Louise-Celeste (born 11 May 1730), daughter of Jean-Louis de Rochechouart, a naval officer and knight of Saint Louis. Their first children were Louis-Jean-Francois (born 25 June 1753) and Louis Charles (born 18 July 1754).[4] His son Pierre Jules Camille (1764–1780) was a lieutenant de vaisseau.[2]

During the Seven Years' War (1756–1763) on 21 January 1758 La Touche was made inspector of naval troops. On 20 November 1759 he participated in the Battle of Quiberon Bay on the Dragon with his son, Louis René.[2]

Governor of Martinique (1761–62)

In 1760 La Touche was appointed governor of Martinique in place of the unpopular François V de Beauharnais, and as a member of the island's Creole[lower-alpha 1] elite helped boost morale.[3] He left for Martinique on the frigate Tigre in late 1760. From 1761 to 1762 he was commander general of the Windward Islands and governor general of Martinique.[2] After La Touche arrived in Martinique in February 1761 he wasted no time. He inspected the small forts and batteries of the island, began to repair the roads, and ordered preparations by the army and militia officers to prepare for the inevitable attack by the British. He printed his ordinances and distributed them throughout the island, the first governor to do so. An ordinance of September 1761 declared the king's satisfaction with the loyalty of the colonists and called on them to defend the island.[3]

The British had invaded Guadeloupe in January 1759, and had overcome resistance after a harsh three-month struggle. The British commander General John Barrington was magnanimous in victory.[5] He let the French planters sell their sugar at good prices in Britain, and over the next three years British ships delivered more than 17,500 slaves to Guadeloupe. The result was a boom in the sugar economy. The planters in Martinique, cut off from their markets and in desperate financial straits, were aware of this. When a large British force landed in January 1762 most of the militia units deserted and the local leaders in the south asked for peace on the same terms as Guadeloupe, ignoring La Touche's call for prolongued resistance. The island had fallen within three weeks.[6] On 13 February 1762 La Touche signed articles of capitulation to the British forces led by Admiral Rodney and General Robert Monckton.[2]

Last years (1763–1781)

In 1771 La Touche was commander of a naval squadron. In 1775 he was naval commander at Rochefort, a position he held until 1781.[2] News of the United States Declaration of Independence reach Paris on 17 August 1776. The French supported the rebels against the British, but France and Britain both strongly wanted to avoid war. Early in August Lord Shelburne announced that he planned to visit France to inspect the seaports. La Touche was told to politely inform Lord Shelburne that the magazines and other restricted depots were always closed to the public. La Touche replied that "Under the appearance of personal attentions, I shall not leave him [Shelburne] for an instant." He would avoid boasting, but instead bewail the mediocrity of the French forces, writing "That will keep him tranquil."[7]

The large transport Hippopotame was sold by the French navy at a low price to a group of merchant from Rochefort in May 1777.[8] The ship's hull required inspection and repair. La Touche made the Rochefort dry dock available for this purpose and work began by the end of July.[9] Various explanations were given for the ship's cargo and destination.[10] The French naval minister Antoine de Sartine discovered that the true purpose was to carry volunteers, munitions and an engineer to America. He asked La Touche to investigate in secret and reply in detail. La Touche was in an awkward position. He wrote back that he had heard the previous Sunday that the purpose was to take a member of Congress to America with a number of cannon, but he knew nothing about the engineer. He added in a footnote that the ship would go first to Santo Domingo, but he did not know the final destination.[11]

In 1779 La Touche was made a Lieutenant General of Naval Armies. He was awarded the Grand Cross of the Order of Saint Louis.[2] He died on 14 April 1781 at the age of 72.[1]

Notes

- The term "Creole" in the French colonies at this time referred to people of French origin who had been born in the colony. It did not imply mixed racial descent.

Citations

- Pierfit.

- Labail et al.

- Banks 2002, p. 205.

- Moréri 1759, p. 254.

- Banks 2002, p. 41.

- Banks 2002, p. 42.

- Morton & Spinelli 2003, p. 355.

- Morton & Spinelli 2003, p. 145.

- Morton & Spinelli 2003, p. 146.

- Morton & Spinelli 2003, p. 147.

- Morton & Spinelli 2003, p. 148.

Sources

- Banks, Kenneth J. (2002-11-21), Chasing Empire Across the Sea: Communications and the State in the French Atlantic, 1713-1763, McGill-Queen's Press - MQUP, ISBN 978-0-7735-2444-6, retrieved 2018-08-11

- Labail, Patrick; Dulou, Bernard; Giran, Stéphane; Jogerst, Gilles, "Louis Charles Le VASSOR de la TOUCHE (marquis)", Ecole navale (in French), retrieved 2018-08-10

- Moréri, Louis (1759), Le grand dictionnaire historique, ou le melange curieux de l'histoire sacree et profane (in French) (Nouv. ed. dans laquelle ou a refondu les supplemens de (Claude-Pierre) Goujet. Le tout revu, corr. & augm. par (Etienne-Francois) Drouet ed.), Assoc, retrieved 2018-08-11

- Morton, Brian N.; Spinelli, Donald C. (2003), Beaumarchais and the American Revolution, Lexington Books, ISBN 978-0-7391-0468-2, retrieved 2018-08-11

- Pierfit, "Louis Charles Le VASSOR de La TOUCHE", Geneanet (in French), retrieved 2018-08-10