Los disparates

Los disparates (The Follies), also known as Proverbios (Proverbs) or Sueños (Dreams), is a series of prints in etching and aquatint, with retouching in drypoint and engraving, created by Spanish painter and printmaker Francisco Goya between 1815 and 1823. Goya created the series while he lived in his house near Manzanares (Quinta del Sordo) on the walls of which he painted the famous Black Paintings. When he left to France and moved in Bordeaux in 1824, he left these works in Madrid apparently incomplete. During Goya's lifetime, the series was not published because of the oppressive political climate and of the Inquisition.

_-_No._13_-_Modo_de_volar.jpg)

The disparates series was first published by the Royal Academy of Fine Arts of San Fernando in 1864 under the title Proverbios[2] (Proverbs). In this edition, the titles given to the works are Spanish proverbs. The series is an enigmatic album of twenty-two prints (originally eighteen; four works were added later) which is the last major series of prints by Goya, which the artist created during the last years of his life. The scenes of the Disparates, which are difficult to explain, include dark, dream-like scenes that scholars have related to political issues, traditional proverbs and the Spanish carnival.[3]

Title and ordering

Although Goya did not name the series, the Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando published eighteen prints in 1864 with the name "Proverbs". Vicente Carderera and Jaime Machén, who first worked on these plates, referred to them as "Caprichos" or "Fantastic Caprices". Later the name "Proverbs" came up, and Carderera referred to the series in 1863 as "Dreams," perhaps because of the dreamlike nature of many of the prints. However, in Goya's artist's proofs, many of the prints contain titles including "Disparates", by which the series is most commonly known today[4].

The academic edition of 1864 used a random sequence, as there was no way to establish the indented ordering of the series[5]. Later, when "state proofs" prepared by Goa were known it was found that there were two numbers, one in the upper left corner and the other in the upper right, which also did not coincide in order. Perhaps because of this, there is no agreement on the logical continuity of this series. The highest number found is 25, which has led specialists to suppose that this was the total number of prints planned[6].

Dating

Los Disparates has been dated to between 1815-1824, the year Goya left Spain. It is thought that the series had twenty-five prints, of which only twenty-two remain. The first would have to have been made immediately upon the completion of La Tauromaquia since in the drawing album that the critic Cean Bermudez had, and which is preserved in the British Museum, the state proof of disparates no. 13 (A way of flying) appears after the last of La Tauromaquia. In addition, the investigations of Jesusa Vega, confirm that the copper plates and the type of paper of the Disparates are the same and belong to the same batch as those used in La Tauromaquia[7].

Valeriano Bozal and other authors, such as Dr. Vega herself, dated the series between 1815 or 1816 and 1819,[8][5] in which, due to the serious illness he suffered, he interrupted the work, which he would not resume and dedicated himself completely to the Black Paintings at his farm in the Quinta del Sordo.[9] Although it cannot be ruled out that Goya continued working on the Disparates between 1819 and 1823, it has been claimed that working on both projects simultaneously would have involved an excessive burden of work for the artist, who was over seventy years old. On the other hand, the satirical charge, violence and buried sexuality of these prints would collide with the Fernandian absolutism of the restoration between 1814 and the Liberal Triennium of Rafael del Riego in 1820. All this leads critics to think that the painter, was not able to or did not consider it convenient to publish them, he must have kept the plates and abandoned the continuation of the series[10]. In any case, it was difficult for such a work to bring him significant economic benefits, given that La Tauromaquia (a series with a more popular theme and therefore with greater commercial possibilities) did not sell as well as expected[11].

The plates of Los Disparates remained in the hands of Goya's descendants until the middle of the 19th century. In 1854, Román Garreta bought eighteen with a view to their publication. Two years later they were in the possession of Jaime Machén, who in 1856 attempted to sell them to the Spanish administration, which was not achieded until 1862, when these eighteen were acquired by the Royal Academy of Fine Arts of San Fernando, which they published in 1864, in a circulation of three hundred and sixty copies[8] in the workshop of Laurenciano Poderno, with the title of Proverbs[8]. Four more plates, belonging to the same series and not published by the Academy, were the property of Eugenio Lucas Velázquez since at least 1856; later they went to France, where they were published in the L'Art magazine in 1877[8]. In July 2011, those four copper plates entered the prints and drawings department of the Louvre

Analysis

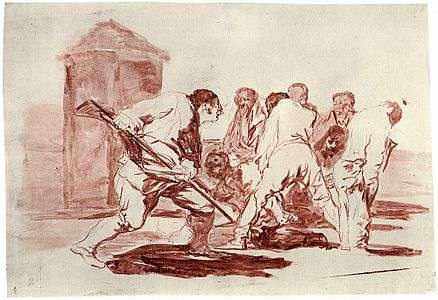

Preparatory drawings in gouache have been conserved of fifteen of prints, for the most part preserved in the Prado[12]. Six other drawings are also known that were not made into prints, giving a total of twenty-one preparatory drawings of Los Disparates. The changes introduced between the drawing and the final print are greater than in the rest of the Goya's graphic work. For example, in the preparatory drawing for Cruel folly (#6)[13], a soldier appears, expelling a group of people with his rifle at a military sentry box. In the final picture the soldier is a civilian, the sentry box has disappeared, and the rifle has become a pike with which it pierces the face of a man.

Los Disparates no.6

Los Disparates no.6 Preparatory drawing for Los Disparates no.6

Preparatory drawing for Los Disparates no.6

For many scholars, the enigma of the work lies in possible iconographic interpretations.[14]. Critics such as Charles Yriarte (among others)[15], saw the series as a continuation of Los Caprichos and with the latest prints of The Disasters of War, the so-called "emphatic caprices". Beyond the semantic relationship between "folly" and "caprice", the recovery of the element of political and social satire, as a common space, was emphasized. Almost all the authors, however, emphasize as characteristic and somewhat exclusive elements of the Disparates, the high degree of fantasy, the presentation of nightmare scenes, the grotesque and monstrous aspect of the characters that inhabit it, together with their lack of logic, or at least a logic different from traditional sanity. All this has made this work be considered closer to the Black Paintings[16][17].

In the 20th century, avant-garde and expressionist artists, such as Paul Klee or Emil Nolde, highlighted the "modernity" of the Disparates, although their interpretations were highly subjective. Attempts have been made to analyze Los Disparates in the light of psychoanalysis[18], emphasizing their sexual and violent character. It has also been proposed to return to the title of Proverbs of the 1864 edition, in this sense of analyzing the series as "an illustration of proverbs or sayings", as happens in the satirical painting of the Netherlands (Such as in the work of Pieter Bruegel the Elder[19].

Nigel Glendinning[20] relates many of the motifs to the tradition of the carnival[8], a line of research suggested by Ramón Gómez de la Serna[8][21]. Glendinning observes that one of the carnival traits is that of subversion of everything that represents authority. Institutions such as marriage, the army and the clergy[22]. In almost all of Los Disparates it is shown how the representation of power is overthrown, humiliated, ignored or ridiculed. In Clear folly (#15)[23], a man in a military outfit appears to be thrown out of a scenario that a group of people are struggling to cover with a tarp. In Feminine folly (#1)[24], a doll thrown by women wears a military uniform. In Fearful folly (#2)[25], a soldier runs away in terror from someone who has disguised himself in large, ghost-like sheets. Despite the fact that the face peeking out from a sleeve gives him away, the military man does not notice it. This satire of the establishment, perhaps a simple Goyesque mockery, is repeated in Carnaval foll (#16) where a military man is seen in the centre of the crowd asleep, possibly drunk or unconscious, but unquestionably presented as ridiculous.

Several critics insist on the leading role of the ridiculed marriage sacrament, and venture possible allusions to the marriage of Leocadia Zorrilla with her husband and the relationship she had with Goya until the painter's death. "The exhortations" (#16), has been interpreted as a reflection on infidelity in which a woman holds a man who is leaving, and who in turn is advised or rebuked by a character who appears to be dressed as a priest . The woman, on the other hand, is drawn by the arm of an old woman of towards two characters with triple and double faces. Another episode of fleeing or escape is presented in Poor folly (#11)[26], or at least flight of a beautiful young woman from an pale character - which has been suggested as a representation of death — and another with tousled hair. The young woman seeks refuge in what appears to be the porch of a church populated by old women, cripples and beggars. The background, between light and dark with burnished aquatint, seems unreal, and gives the print a light from another world. Relations between women and old wretches reappear in Merry folly (#12)[27], where an old man with a huge truss dances in a circle with women with large cleavages.

The prints that suggest satires of vices are equally enigmatic and abound in the absence of logical parameters that allow us to decipher the subject of the prints. Flying Nonsense shows a strange flying mythological animal or being, perhaps a hippogriff[28], whose haunches are ridden by a man and a woman. She seems to struggle as if she had been kidnapped against her will, or she has eloped with her lover and her uneasiness is an allegory of sexual debauchery. Another equine parable, in Kidnapping horse (#10)[29][30], shows a woman snatched by a bite by a horse, an animal symbolically associated with sexual potency[31].

The works of the series

The prints of the plates that are displayed below were published in 1864 (first edition) and are part of the collection of Museo Nacional del Prado The dimensions given refer to the size of the image (also called the platemark) rather than the sheet, as the printed image remained the same size while the size of the sheet varies with different versions.[a 1]

_-_No._01_-_Disparate_femenino.jpg) Νο. 1: Disparate femenino

Νο. 1: Disparate femenino

(Feminine folly)

24.3 x 35.3 cm_-_No._02_-_Disparate_de_miedo.jpg) Νο. 2: Disparate de miedo

Νο. 2: Disparate de miedo

(Fearful folly)

24.4 x 35,3 cm._-_No._03_-_Disparate_rid%C3%ADculo.jpg) Νο. 3: Disparate ridículo

Νο. 3: Disparate ridículo

(Ridiculous folly)

24.5 x 35.3 cm._-_No._04_-_Bobalic%C3%B3n.jpg) Νο. 4: Bobalicón

Νο. 4: Bobalicón

(Simpleton's folly)

24.3 x 35.2& cm._-_No._05_-_Disparate_volante.jpg) Νο. 5: Disparate volante

Νο. 5: Disparate volante

(Flying folly)

24.4 x 35.2 cm._-_No._06_-_Disparate_cruel.jpg) Νο. 6: Disparate cruel

Νο. 6: Disparate cruel

(Cruel folly)

24.3 x 35.1 cm._-_No._07_-_Disparate_desordenado.jpg) Νο. 7: Disparate desordenado

Νο. 7: Disparate desordenado

(Disordered folly)

24.4 x 35.2 cm._-_No._08_-_Los_ensacados.jpg) Νο. 8: Los ensacados

Νο. 8: Los ensacados

(Folly in sacks)

24.4 x 35.1 cm._-_No._09_-_Disparate_general.jpg) Νο. 9: Disparate general

Νο. 9: Disparate general

(General folly)

24.1 x 35.1 cm._-_No._10_-_El_caballo_raptor.jpg) Νο. 10: El caballo raptor

Νο. 10: El caballo raptor

(Kidnapping horse)

24.4 x 35.3 cm._-_No._11_-_Disparate_pobre.jpg) Νο. 11: Disparate pobre

Νο. 11: Disparate pobre

(Poor folly)

24.4 x 35.2 cm._-_No._12_-_Disparate_alegre.jpg) Νο. 12: Disparate alegre

Νο. 12: Disparate alegre

(Merry folly)

24.3 x 35.2 cm._-_No._13_-_Modo_de_volar.jpg)

_-_No._14_-_Disparate_de_carnaval.jpg) Νο. 14: Disparate de carnaval

Νο. 14: Disparate de carnaval

(Carnaval folly)

24.2 x 35.2 cm._-_No._15_-_Disparate_claro.jpg) Νο. 15: Disparate claro

Νο. 15: Disparate claro

(Clear folly)

24,3 x 35,2 cm._-_No._16_-_Las_exhortaciones.jpg) Νο. 16: Las exhortaciones

Νο. 16: Las exhortaciones

(The exhortations)

24.4 x 35.3 cm._-_No._17_-_La_lealtad.jpg) Νο. 17: La lealtad

Νο. 17: La lealtad

(Loyalty)

24.4 x 35.1 cm._-_No._18_-_Disparate_f%C3%BAnebre.jpg) Νο. 18: Disparate fúnebre

Νο. 18: Disparate fúnebre

(Funereal folly)

24.3 x 35.2 cm.

The 4 works which were added later

_-_Disparate_de_toritos.jpg) Disparate de toritos, 24,3 x 35,5 cm. (platemark)/30,6 x 44,5 cm. (sheet)

Disparate de toritos, 24,3 x 35,5 cm. (platemark)/30,6 x 44,5 cm. (sheet)_-_Disparate_de_bestia.jpg) Disparate de bestia, 24,3 x 35,5 cm. (platemark)/30 x 42,8 cm. (sheet)

Disparate de bestia, 24,3 x 35,5 cm. (platemark)/30 x 42,8 cm. (sheet)_-_Disparate_conocido.jpg) Disparate conocido, 24,2 x 35,6 cm. (platemark)/30,1 x 44,1 cm. (sheet)

Disparate conocido, 24,2 x 35,6 cm. (platemark)/30,1 x 44,1 cm. (sheet)_-_Disparate_puntual.jpg) Disparate puntual, 24,6 x 35,6 cm. (platemark)/30,2 x 43,8 cm. (sheet)

Disparate puntual, 24,6 x 35,6 cm. (platemark)/30,2 x 43,8 cm. (sheet)

Preparatory drawings for the series

Goya produced gouache drawings for fifteen of the prints. All drawings except for Modo de Volar are from the collection of the Prado Museum[32].

Drawing for Disparate femenina

Drawing for Disparate femenina Drawing for Disparate de miedo

Drawing for Disparate de miedo Drawing for Disparate ridículo

Drawing for Disparate ridículo Drawing for Bobalicón

Drawing for Bobalicón Drawing for Disparate cruel

Drawing for Disparate cruel Drawing for Disparate desordenado

Drawing for Disparate desordenado Drawing for Los ensacados

Drawing for Los ensacados Drawing for Disparate general

Drawing for Disparate general Drawing for El Caballo raptor

Drawing for El Caballo raptor Drawing for Disparate pobre

Drawing for Disparate pobre Drawing for Disparate alegre

Drawing for Disparate alegre Drawing for Modo de Volar

Drawing for Modo de Volar Drawing for Disparate claro

Drawing for Disparate claro Drawing for Las exhortaciones

Drawing for Las exhortaciones Drawing for La lealtad

Drawing for La lealtad

Drawings not turned into prints

_drawing.jpg) Los elefantes (Disparate de bestia)

Los elefantes (Disparate de bestia) La desesperación de Satán

La desesperación de Satán El tragafuego

El tragafuego Dos personajes asomándose a una salida luminosa

Dos personajes asomándose a una salida luminosa Personajes trepando sobre un gigante acostado

Personajes trepando sobre un gigante acostado El pavo real vanidoso

El pavo real vanidoso

Notes

- The images are available on the website of the museum which is the source of the dimensions and the Spanish titles of the works mentioned in this article. The source of the English titles is goya.unizar.es.

References

- Hughes, (1990), 63

- Ives, Colta Feller & Susan Alyson Stein (en inglés): Goya in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, pp. 26-8. Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York, N.Y.) 1995. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 7 May 2017.

- The University of Arizona Museum of Art

- Bozal, (2005), Vol. II, pp. 200-03

- Bozal, (1994), p. 57

- Bozal, Valeriano (2009). Pinturas negras de Goya. Madrid: Machado Grupo de Distribución SL. ISBN 978-84-9114-038-2.

- Vega, Jesusa (2005). El comercio de estampas en Madrid durante la Guerra de la Independencia. Mísera humanidad, la culpa es tuya: estampas de la Guerra de la Independencia. Madrid: Calcografía Nacional y Caja de Asturias.

- "Estampas de Goya - Introducción". Spanish national library. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- Gaspar Gómez, (1969), pp. 239-41

- Carrete Parrondo, Juan; Centellas Salamero, Ricardo; Fatás Cabeza, Guillermo (1996). Goya ¡Qué valor! V. Disparates. Zaragoza: Caja de Ahorros de la Inmaculada. ISBN 84-88305-35-4.

- "Estampas de Goya - La Tauromaquia". Biblioteca Nacional de España. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- "los disparates". Museo del Prado. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- Camón Aznar, José. "Disparate furioso. Francisco de Goya". Youtube. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- Gaspar Gómez, (1969), p. 237

- Yriarte, Charles. "LA SEÑAL DE GOYA Los Disparates en la Escuela" (PDF). .fundaciongoyaenaragon.es. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- Bozal, (1994), pp. 57-58

- Gaspar Gómez, (1969), pp. 240-41

- Blas, Javier. "Disparates". Royal Academy of Fine Arts of San Fernando. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- Foucaut, Michel (2015). Historia de la locura en la época clásica, II. Fondo de Cultura Económica. ISBN 9786071631084.

- Glendinning, Nigel (1992). Francisco de Goya grabador: instantáneas. Disparates. Madrid: Casser/Turner. ISBN 9788486633196.

- Ramon Gómez, (1958), pp.95-101

- Glendinning, 1993

- "Disparate claro". Museo del Prado. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- "Disparate femenino". Museo del Prado. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- "Disparate de miedo". Goya at the Prado. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- "Disparate pobre". Museo del Prado. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- "Disparate alegre". Museo del Prado. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- "Disparate volante". Museo del Prado. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- "El caballo raptor". Museo del Prado. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- Bozal, Valeriano (2010). Goya. Madrid: Machado Grupo de Distribución SL. p. 110. ISBN 978-84-9114-112-9.

- Cirlot, Juan-Eduardo (1991). Diccionario de Símbolos. Barcelona: Editorial Labor. p. 110.

- "Disparates". Goya en el Prado. Retrieved 15 June 2020.

Bibliography

- Bozal, Valeriano (2005). Franciso Goya, life and work II. 2 vols. Madrid: Tf Editores. pp. 199-217. ISBN 84-96209-39-3.

- Bozal, Valeriano (1994). Goya (1994 edition). Madrid: Alianza Editorial. pp. 57-60. ISBN 8420646539.

- Carrete Parrondo, Juan; Centellas Salamero, Ricardo; Fatás Cabeza, Guillermo (1996). Goya ¡Qué valor! V. Disparates. Zaragoza: Caja de Ahorros de la Inmaculada. ISBN 84-88305-35-4.

- Glendinning, Nigel (1993). "Francisco de Goya", Art and its creators. Cuadernos de Historia 16 (30). D.L.34276-1993.

- Gómez de la Serna, Gaspar (1969). Goya and his Spain. Madrid: Alianza Editorial. ISBN 9788420611853.

- Gómez de la Serna, Ramón (1958). "VI.5". Goya (Austral collection edition). Espasa Calpe. pp. 95-101. ISBN 9788423909209. «El ‘Deseado’ y otros disparates».

Further reading

- Goya in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. 1995. ISBN 9780870997525.

External links

- Goya en el Prado, Disparates

- Cushing, Douglas (2015-02-23). "Beyond All Reason: Goya and his Disparates". Blanton Museum of Art.

- Lubbock, Tom (1997-03-11). "Culture: Disparate Goya". The Independent.