Los Angeles City Hall

Los Angeles City Hall, completed in 1928, is the center of the government of the city of Los Angeles, California, and houses the mayor's office and the meeting chambers and offices of the Los Angeles City Council.[5] It is located in the Civic Center district of downtown Los Angeles in the city block bounded by Main, Temple, First, and Spring streets, which was the heart of the city's central business district during the 1880s and 1890s.

| Los Angeles City Hall | |

|---|---|

| |

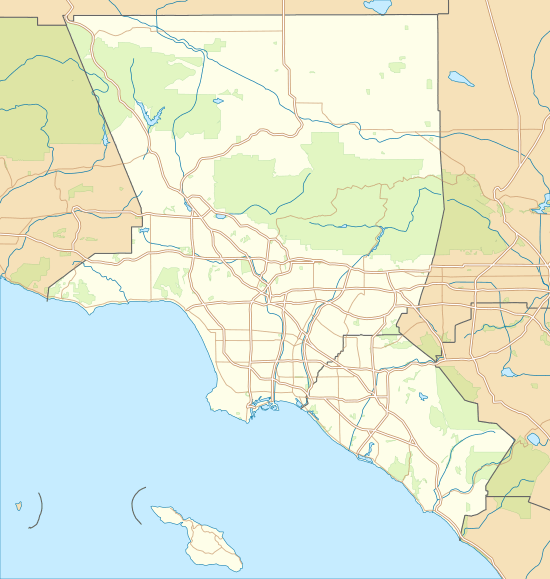

Location within the Los Angeles metropolitan area  Los Angeles City Hall (California)  Los Angeles City Hall (the United States) | |

| General information | |

| Status | Complete |

| Type | Government offices |

| Location | 200 North Spring Street Los Angeles, California |

| Coordinates | 34.0536°N 118.2430°W |

| Construction started | 1926 |

| Completed | 1928 |

| Owner | City of Los Angeles |

| Management | City of Los Angeles |

| Height | |

| Roof | 138 m (453 ft) |

| Technical details | |

| Floor count | 32 |

| Floor area | 79,510 m2 (855,800 sq ft) |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect | Austin, Parkinson and Martin |

| Structural engineer | Nabih Youssef Associates |

| Main contractor | Bovis Lend Lease |

| Designated | March 24, 1976 |

| Reference no. | 150 |

| References | |

| [1][2][3][4] | |

History

The building was designed by John Parkinson, John C. Austin, and Albert C. Martin, Sr., and was completed in 1928. Dedication ceremonies were held on April 26, 1928. It has 32 floors and, at 454 feet (138 m) high, is the tallest base-isolated structure in the world, having undergone a seismic retrofit from 1998 to 2001 so that the building will sustain minimal damage and remain functional after a magnitude 8.2 earthquake.[7] The concrete in its tower was made with sand from each of California's 58 counties and water from its 21 historical missions.[2] City Hall's distinctive tower was based on the shape of the Mausoleum of Mausolus,[8] and shows the influence of the Los Angeles Public Library, completed shortly before the structure was begun. An image of City Hall has been on Los Angeles Police Department badges since 1940.[9]

To keep the city's architecture harmonious, prior to the late 1950s the Charter of the City of Los Angeles did not permit any portion of any building other than a purely decorative tower to be more than 150 ft (46 m). Therefore, from its completion in 1928 until 1964, the City Hall was the tallest building in Los Angeles, and shared the skyline with only a few structures having decorative towers, including the Richfield Tower and the Eastern Columbia Building.

City Hall has an observation deck, free to the public and open Monday through Friday during business hours. The peak of the pyramid at the top of the building is an airplane beacon named in honor of Colonel Charles A. Lindbergh, the Lindbergh Beacon. Circa 1939, there was an art gallery, in Room 351 on the third floor, that exhibited paintings by California artists.[10]

The building was designated a Los Angeles Historic-Cultural Monument in 1976.[11]

In 1998 the building was closed during a total $135 million refurbishment which also included upgrading it so it could withstand a magnitude 8.2 earthquake including permitting it to sway in a quake.[12]

Previous City Halls

Prior to the completion of the current structure, the L.A. City Council utilized various other buildings:

- 1850s: used rented hotel and other buildings for city meetings[13]

- 1860s: rented adobe house on Spring Street—across from current City Hall (now parking lot for Clara Shortridge Foltz Criminal Justice Center)[13]

- 1860s–1884: relocated to Los Angeles County Court House[13]

- 1884–1888: moved to Mirror Building at South Spring Street and West 2nd Street (site of current Los Angeles Times Building)[13]

- 1888–1928: moved to new Romanesque Revival building on 226-238 South Broadway between 2nd Street and 3rd Street;[14] demolished in 1928 and now site of parking lot between LA Times parking structure and 240 Broadway.[15]

Usage

The Mayor of Los Angeles has an office in room 300 of this building and every Tuesday, Wednesday and Friday at 10:00am, the Los Angeles City Council meets in its chamber. City Hall and the adjacent federal, state, and county buildings are served by the Civic Center station on the LA Metro Red Line and Purple Line. The Silver Line stops in front of the building.

An observation level is open to the public on the 27th floor. The interior of this floor, comprises a single large and highly vaulted room distinguished by the iconic tall square columns that are far more familiar as one of the building's most distinguishing exterior features. The Mayor Tom Bradley Room, as this large interior space is named, is used for ceremonies and other special occasions.

The Los Angeles Dodgers wore a commemorative uniform patch during the 2018 season celebrating 60 years in the city depicting a logo of Los Angeles City Hall.

Filming location

The building has been featured in the following popular movies and television shows:

- While the City Sleeps (1928): The newly constructed building appears in the background of some exterior shots in this silent crime drama starring Lon Chaney, even though the film is set in New York.

- Adventures of Superman: The building appears as the Daily Planet building beginning in the second season of the 1950s TV series. At the time the TV program was broadcast, the show's Daily Planet building (Los Angeles City Hall) was frequently confused with the similarly designed Pennsylvania Power & Light Building in Allentown, also built in 1928. Additionally, the exact design of this building is used as the Newstime magazine headquarters in the Superman comic books.

- Alias: A CIA black ops unit is located behind a maintenance door at Civic Station.

- Dragnet: The building appears as itself in the TV series. The first episode of Dragnet (1951) Season 1, Episode 1: "The Human Bomb", original air date 16 December 1951, was filmed at Los Angeles City Hall. It was embossed on Sgt. Joe Friday's famous badge number 714 that was displayed under the credits.

- Perry Mason: The City Hall building appears in the view from Perry's office window. This has led viewers of the show to speculate where the fictional office would have been located in downtown Los Angeles.[16]

- L.A. Confidential: The police in the 1997 neo-noir film operate out of the City Hall, as well as the police badges featuring a depiction the building itself.[17] At the time the film takes place no building in Los Angeles was allowed to be taller than City Hall, so the cameras were placed at certain points so that any building taller than City Hall would not be seen.[18]

- Tower of Terror: In this 1997 made-for-TV movie, the main character's love interest works at a fictional newspaper, The Los Angeles Banner. The newspaper's logo is based on the top of City Hall.

- Adam-12: During the seventh season opening credits montage, City Hall is shown directly at the end, as the building that officers Reed and Malloy drive away from. It is also shown on the embossed badges numbered 744 (Malloy) and 2430 (Reed).

- The 2003 Dragnet series used the L.A. City Hall building aerial shot and badge throughout its introduction.

- War of the Worlds: The City Hall was destroyed (albeit by miniature) in the 1953 film version (although the H. G. Wells book has the aliens attacking London, the setting was changed to Los Angeles for the film).

- V: City Hall was destroyed when the Visitors attack Earth. The same footage of the tower being destroyed from War of the Worlds was used but with different energy weapons superimposed.

- The 1976 film The Bad News Bears included a scene both shot and set in the city council chamber that included a close-up of the electronic voting board with the names of the incumbent council members.

- The 1991 music video for Prince's "Diamonds and Pearls" features City Hall as the primary location.

- The 2011 film Atlas Shrugged: Part I.

- The 2011 series Torchwood: Miracle Day used the main entrance of City Hall to represent the CIA archive Esther Drummond visits in "The New World", and the exterior to the medical conference where Vera Juarez meets Jilly Kitzinger in "Rendition"/"Dead of Night".

- The 2013 film The Employer uses City Hall as the headquarters of the fictional Carcharias Corporation.

- The 2013 film Gangster Squad features the Los Angeles City Hall, with the members of the Gangster Squad stood in the foreground of the building, as well as it being used in the background of some scenes. Mayor Villaraigosa's conference room was also used for the office of Police Chief Parker.

Gallery

Detailed top of City Hall.

Detailed top of City Hall. The silhouette of City Hall at sunrise.

The silhouette of City Hall at sunrise. Stairs of the city hall

Stairs of the city hall- Seen at night from the Walt Disney Concert Hall.

.jpg) During the day from the Walt Disney Concert Hall.

During the day from the Walt Disney Concert Hall. City Hall with a street sign indicating Los Angeles' twin towns and sister cities.

City Hall with a street sign indicating Los Angeles' twin towns and sister cities. As seen from Grand Park.

As seen from Grand Park. City Hall at night from Grand Park.

City Hall at night from Grand Park.

See also

References

- Los Angeles City Hall at Emporis

- Los Angeles City Hall at Glass Steel and Stone (archived)

- "Los Angeles City Hall". SkyscraperPage.

- Los Angeles City Hall at Structurae

- "The Official Web Site of The City of Los Angeles". City of Los Angeles. 2010. Archived from the original on 13 November 2010. Retrieved 28 May 2010.

- Scott, Charles Fletcher (August–September 1931). "Los Angeles on Parade". Overland Monthly. 89 (8–9): 14.

- "Projects". Clark Construction Group, LLC. 2010. Archived from the original on February 19, 2013. Retrieved 28 May 2010.CS1 maint: unfit url (link)

- Kimberly Truhler (February 13, 2012). "Out & About--the Art Deco Design of Los Angeles City Hall". GlamAmor. Retrieved 13 August 2013.

- "LAPD Badge Description". Los Angeles Police Department. 2010. Retrieved 5 June 2010.

- Work Progress Administration (1939). Los Angeles: A Guide to the City and Its Environs. ASIN B00XZS6OG8.

- Los Angeles Department of City Planning (September 7, 2007). "Historic - Cultural Monuments (HCM) Listing: City Declared Monuments" (.PDF). City of Los Angeles. Retrieved 5 June 2010. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Los Angeles City Hall: Restoring & Protecting a Downtown Icon". Clark Construction.

- Cecilia Rasmussen (September 9, 2001). "City Hall Beacon to Shine Again". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 13 August 2013.

- Pacific Electric (March 22, 2013). "Early Los Angeles City Hall on Broadway". Pacific Electric Railway Historical Society. Retrieved 13 August 2013.

- J Scott Shannon (November 22, 2009). "Old Civic Center – south to City Hall". Los Angeles Past. Retrieved 13 August 2013.

- "Perry Mason office locale". D M Brockman. 2007. Retrieved 5 November 2010.

- Tony Reeves. "Film Locations for L.A. Confidential(1997)". Archived from the original on 30 January 2012. Retrieved 19 February 2013.

- IMDB. "L.A. Confidential (1997) - Trivia - IMDB)". Retrieved 19 February 2013.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Los Angeles City Hall. |

- History of and guide to Los Angeles City Hall—with maps and photos

_edit1.jpg)