Lordship of Biscay

The Lordship of Biscay (Spanish: Señorío de Vizcaya, Basque: Bizkaiko jaurerria) was a region under feudal rule in the region of Biscay in the Iberian Peninsula between c.1040 and 1876, ruled by a political figure known as the Lord of Biscay. One of the Basque señoríos, it was a territory with its own political organization, with its own naval ensign, consulate in Bruges and customs offices in Balmaseda and Urduña, from the 11th Century until 1876, when the Juntas Generales were abolished. Since 1379, when John I of Castile became the Lord of Biscay, the lordship got integrated into the Crown of Castile, and eventually the Kingdom of Spain.

Lordship of Biscay Señorío de Vizcaya Bizkaiko jaurerria | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c.1040–1876 | |||||||

Coat of arms

| |||||||

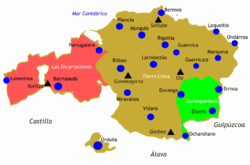

The Lordship of Biscay and its three constituent parts | |||||||

| Status | Vassal first of the Kingdom of Navarre, then of the Kingdom of Castile | ||||||

| Capital | Bermeo (1476–1602) Bilbao (1602–1876) | ||||||

| Government | Lordship | ||||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages | ||||||

• Established | c.1040 | ||||||

• Abolition of the Juntas Generales | 1876 | ||||||

| |||||||

Mythical foundation

The first explicit reference to the foundation of the Biscayan lordship is in the Livro de Linhagens, written between 1323 and 1344 by Pedro Afonso, Count of Barcelos. It is an entirely legendary account. The book narrates the arrival in Biscay of a man named Froom, a brother of the King of England, who had expelled him from his kingdom. Froom along with his son, Fortun Froes, defeat the Asturians in Busturia. Froom is killed in battle; his son was named the first Lord of Biscay. The Count of Barcelos then lists six additional mythical lords before he comes to Lope, the historical late-11th century lord, Lope Íñiguez.[1] A notable story among these accounts, which bears some resemblance to the Melusine legend, is that of the Lady of Biscay (La Dama de Viscaya), a beautiful stranger found in the countryside by Lord Diego López. She joins him only when he agrees to certain conditions, but he later violates these and she flees into the country with their daughter. Diego López is subsequently captured by Moors, and their son Enheguez Guerra seeks out his mother for help. She gives him a horse, Pardalo, with whom he frees his father and is subsequently successful in all his battles. The later lords are said to have made sacrifices at Busturia in thanks for these events, their failure to do so resulting in attacks on the lords and townsmen by a mysterious knight.[2]

A better known but equally mythical story appears in the Bienandanzas e Fortunas of Lope García de Salazar (1454). In this story, a man named Çuria is born from the union of the god Sugaar and a Scottish (or in other versions, Irish, Danish or Frankish) princess in the village of Mundaka. Çuria was the elected chief of the Biscayans before the victorious battle of Arrigorriaga against the invading forces of the Kingdom of Asturias. Tradition holds that before the battle he saw two wolves carrying lambs in their mouths, presaging the victory; this scene is reflected in the arms of the lords of Biscay of the House of Haro. García de Salazar proceeds to give Çuria two sons by different mothers, Munso López (perhaps representing the historical Munio Velaz of the early 10th century) and Ínigo Esquira (an apparent temporally-displaced doppelgänger of the later lord of that name), who are followed by further apocryphal lords, Lope Díaz and Sancho López, before García de Salazar names a second Ínigo Esquira, this time representing the first authentic Lord of Biscay, the 11th-century Íñigo López Ezkerra. This tale of Çuria would further develop into the legend of Jaun Zuria (the White Lord) of Biscay, treated as a historical figure perhaps identical to Froom by 19th century historians.[3]

The 16th-century historian Gonzalo Argote de Molina tells of other legendary lords of Biscay, and in this he is followed by several 17th and 18th century historians. They name a Hudon (or Eudon), the son of a Duke of Cantabria, who became lord of Biscay and who had a son named Zeno who succeeded him in the title. Hudon and Zeno are variously placed at different dates ranging from the mid-8th century to the late 9th century, and while the precise details differ in the different accounts, they are described as being related by marriage to the King of Pamplona and to Jaun Zuria.[4][5][6][7] As with Froom and Çuria, there is no historical basis for these men.

History

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of the Basques |

|

|

Prehistory and Roman Empire

|

|

Late Middle Ages |

|

19th century |

|

20th and 21st centuries

|

Biscay before the lordship

The first time Biscay is mentioned with that name (in Spanish, Vizcaya) is in the Chronicle of Alfonso III in the late 9th century, which tells of the regions repopulated under orders of Alfonso I, and how some territories "owned by their own", among them Biscay, were not affected by these repopulations. Biscay is mentioned again in the 10th-century Códice de Roda, which narrates the wedding between Velazquita, daughter of Sancho I of Pamplona, to Munio Velaz, Count of Álava, in Biscay. It is considered then, that Biscay was by this period controlled by the Kingdom of Navarre.[8]

House of Haro

In 1076, after the assassination of Sancho IV of Navarre, Alfonso VI of León and Castile and Sancho Ramírez of Aragón fought a war over control of the Kingdom of Navarre. Count Íñigo López, lord of Biscay surrendering the fortress of Bilibio to the Leonese, which aided in their conquest of La Rioja. In exchange, the Leonese monarchs promised to support Íñigo's personal interests in Durangaldea, Gipuzkoa and Álava. Íñigo died in 1077, and his son, Lope Íñiguez became Lord of Biscay, now as vassal of the Kingdom of Castile.[8] The lordship would be later inherited by his son, Diego López I de Haro, who served as Lord of Biscay until 1134 when he was defeated and probably killed by Alfonso the Battler, King of Aragón and Navarre. The Lordship was then reintegrated into Navarre and Ladrón Íñiguez, one of the most powerful men of the Navarrese court, was named Lord of Biscay. After his death, in 1155, his son Vela Ladrón, who at the time was also Lord of Álava and Guipúzcoa, became Lord of Biscay and ruled through the reigns of Alfonso the Battler, García Ramírez and Sancho VI. During that time, Lope Díaz I de Haro claimed the title of Lord of Biscay, though he never set foot on the land during his lifetime. In 1173 Alfonso VIII of Castile attacked the Kingdom of Navarre and, a year later with the death of Vela Ladrón, occupied Biscay and restored the House of Haro: Diego López II de Haro was named Lord of Biscay.

In 1176 the kingdoms of Navarre and Castile signed a declaration of peace, agreeing to arbitration by Henry II of England. New borders were delimited and ratified in 1179. Biscay was divided, with the left bank of the River Nervión becoming part of Castile, while the rest of Biscay, Durangaldea and Álava (east from the Bayas River) were retained by Navarre. Diego López II, Lord of Biscay, swore fealty to the Navarrese monarchy and he ruled Biscay until 1183. The Lords of Biscay were vassals of the Kingdom of Navarre until 1206, when the Haro family were given the title of alférez at the Castilian court, and thereafter Biscay was in the area of influence of the Castilian kingdom, though it would not be wholly integrated into it until much later.

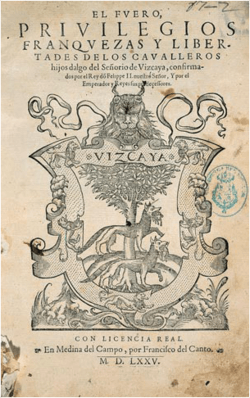

Crown domain

The Lordship of Biscay was in the hands of the Haro family and their descendants through 1370, when it passed to prince Juan of Castile, a distant kinsman with a maternal descent from the earlier Lords. He would subsequently succeed to his father's Kingdom of Castile, and from that time the Lordship remained bound to the Castilian kingdom, and from the reign of Charles I, to the Spanish crown. However, the Lordship maintained a high degree of autonomy, through the Biscayan law, or fueros.

In 1874, after the abolishment of the First Spanish Republic and the beginning of the Restoration, Alfonso XII abolished the Biscayan law and Juntas Generales; putting the Lordship to an end. Since then, Biscay has been fully integrated into the Spanish crown as the province of Biscay.

Territory

Tierra Llana

Tierra Llana (literally, flatlands) refers to the territory that was not protected by stone walls, that is, mostly rural areas and farms. This territory was organized into 72 elizates, grouped in six merindades. Each elizate had a representation in the Juntas Generales.

- Merindad of Busturia (26 elizates): Mundaka (1st), Sukarrieta (2nd), Busturia (3rd), Murueta (4th), Forua (5th), Lumo (6th), Muxika (7th), Arrieta (8th), Mendata (9th), Arratzu (10th), Ajangiz (11th), Ereño (12th), Ibarrangelu (13th), Gautegiz Arteaga (14th), Kortezubi (15th), Natxitua (16th), Ispaster (17th), Bedarona (18th), Aulesti (19th), Nabarniz (20th), Gizaburuaga (21st), Amoroto (22nd), Mendexa (23rd), Berriatua (24th), Ziortza (25th) and Arbatzegi (26th).

- Merindad of Markina (2 elizates): Xemein (27th) and Etxebarria (28th).

- Merindad of Zornotza (3 elizates): Amorebieta (29th), Etxano (30th) and Ibarruri (31st).

- Merindad of Uribe (32 elizates): Gorozika (32nd), Barakaldo (33rd), Abando (34th), Deusto (35th), Begoña (36th), Etxebarri (37th), Galdakao (38th), Arrigorriaga (39th), Arrankudiaga (40th), Lezama (41st), Zamudio (42nd), Loiu (43rd), Sondika (44th), Erandio (45th), Leioa (46th), Getxo (47th), Berango (48th), Sopelana (49th), Urduliz (50th), Barrika (51st), Gorliz (52nd), Laukiz (53rd), Gatika (54th), Lemoiz (55th), Maruri (56th), Bakio (57th), Morga (58th), Mungia (59th), Gamiz (60th), Fika (61st), Fruiz (62nd), Meñaka (63rd) and Derio (72nd).

- Merindad of Bedia (1 elizate): Lemoa (64th).

- Merindad of Arratia (7 elizates): Igorre (65th), Arantzazu (66th), Artea (67th), Zeanuri (68th), Dima (69th), Zeberio (70th) and Ubide (71st).

All these regions were governed by the Biscayan law, or fuero. There were five de facto elizates, who did not belong to any merindad nor have any representation in the Juntas. Those were Alonsotegi, Arakaldo, Basauri, Zaratamo and Zollo.

Cities and towns

There were 21 walled cities and towns, all founded during the Middle Ages. They were the towns of Balmaseda, Bermeo, Bilbao, Durango, Ermua, Gernika, Lanestosa, Lekeitio, Markina, Ondarroa, Otxandio, Portugalete, Plentzia, Mungia, Areatza, Errigoiti, Larrabetzu, Gerrikaitz, Miraballes, Elorrio and Urduña. There towns had their own municipal charter or carta puebla, with their own set of laws different from those of the fueros.

Enkarterri

The region known as Enkarterri (Encartaciones in Spanish) is located at the west of the River Nervión and was incorporated into the Lordship in the 13th Century by the House of Haro. It was traditionally formed by 10 republics, that were united in councils, each with its own representation and government. Enkarterri had its own junta and fueros, but eventually adopted the ones from Vizcaya. Their representatives held councils in Avellaneda. A single common representative of all of them assisted the Biscayan Juntas Generales. In the 17th Century, five of the councils got their own representative in the Juntas. In 1804, the Junta of Avellaneda was dissolved and its councils incorporated into the Tierra Llana. The Enkarterri had the following councils: Karrantza, Trutzioz, Artzentales, Sopuerta, Galdames, Zalla, Güeñes, Gordexola, The Three Councils of the Somorrostro Valley (Santurtzi, Sestao and Trapagaran) and The Four Councils of the Somorrostro Valley (Muskiz, Zierbena, Abanto de Suso and Abanto de Yuso).

Durango

The region known as the County of Durango (Merindad de Durango in Spanish) and currently known as Durangaldea is a valley located along the upper river Ibaizabal and had the traditional name of Merindad of Durango. Durango and its valley were a semi-autonomous region, controlled by the Kingdom of Pamplona (later, Navarre) and had its own Foral law, and celebrated its own council mettings in Gerediaga. In 1200 it was conquered by the Kingdom of Castile, and in 1212 Alfonso VIII of Castile gives the land to Diego López II de Haro, Lord of Biscay, as a reward for his services in the Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa, being then incorporated into Biscay. The Merindad of Durango comprised the following elizates: Abadiño, Berriz, Mallabia, Mañaria, Iurreta, Garai, Zaldibar, Arratzola, Axpe, Atxondo, Izurtza and Elorrio.

Political institutions

Juntas Generales

The Biscayan Juntas Generales were the maximum governing body of the Lordship; in the Juntas were represented all the Biscayan territories. There were in total 72 representatives; each elizate had one, the towns and cities had one each.[9]

Regiment

The Regimiento General (General Regiment) was established in 1500 and had the function of governing the territory when the Juntas were not meeting. It was formed by 12 regidores that were named by the Juntas and one corregidor. The regiment meet three times each year, and eventually got the name of Universal government of the Lordship.

The Regimiento Particular (Particular Regiment) was established in 1570 and had the function of governing in the General Regiment's absence. It was formed by all the regidores that lived in Bilbao.[10]

Diputación General

It served as the fundamental political institution of the Lordship during the 18th Century. In 1645 the Particular Regiment changed its name to Diputación General and were granted autonomy from the General Regiment. It was formed by seven members; six general members and one president, who was the corregidor. Its function was to govern the Juntas Generales, the Diputación had competences in military and financial issues, as well as the maintenance of the roads and charities.[11]

List of lords

The Lord of Biscay is the title that was granted to those who controlled the Biscayan territory.

House of Haro

- Íñigo López Ezkerra (The Left-Handed), 1040-1077

- Lope Íñiguez, 1077-1093, son of Íñigo López

- Diego López I the White, 1093-1124, son of Lope Íñiguez

House of Vela

- Íñigo Vélaz, 1124-c. 1131

- Ladrón Íñiguez Navarro, c. 1131-1155, son of Íñigo Vela

- Vela Ladrón, 1155-1162, son of Ladrón Íñiguez

House of Haro (restored)

- Lope Díaz I, the one from Nájera, 1162-1170, son of Diego López I

- Diego López II the Good, 1170-1214, son of Lope Díaz I

- Lope Díaz II Brave Head, 1214-1236, son of Diego López II

- Diego López III, 1236-1254, son of Lope Díaz II

- Lope Díaz III, 1254-1288, son of Diego López III

- Diego López IV the Young, 1288-1289, son of Lope Díaz III

- María Díaz I the Good, 1289-1295 (first tenure), daughter of Lope Díaz III

- Diego López V the Intruder, 1295-1310, son of Diego López III

- María Díaz I the Good, 1310-1322 (second tenure)

- Juan de Castilla y Haro the One-eyed, 1322-1326 son of María Díaz I de Haro

- María Díaz I the Good, 1326-1333, (third tenure)

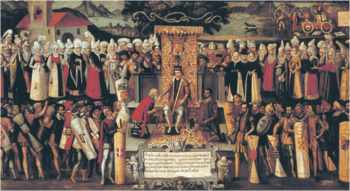

Painting by Francisco de Mandieta.

House of Burgundy

- Alfonso XI of Castile, 1333-1334

- Juan Núñez III de Lara, 1334-1350, great-grandson of Diego López III de Haro, jointly with wife María Díaz II de Haro, 1334-1348, daughter of Juan de Castilla y Haro

- Nuño Díaz de Lara, 1350-1352, son of Juan Núñez de Lara and María Díaz II de Haro

- Juana de Lara, 1352-1359, daughter of Juan Núñez and María Díaz II

- Isabel de Lara, 1359-1361, daughter of Juan Núñez and María Díaz II

House of Burgundy/Trastamara

- Tello Alfonso, 1366-1370, son of Alfonso XI of Castile, widower of Juana de Lara. On his death without legitimate children, the title passed to his nephew, who was also a kinsman of the Lara and Haro.

- John I of Castile, 1370-1379, son of Henry II of Castile and grandnephew of Biscay lord Juan Núñez III de Lara.

With the succession of John I as King of Castile in 1379, the Lordship of Biscay was united with the Crown of Castile. Subsequent Castilian monarchs as well as their successors who ruled all Spain have continued to claim the title of Lord of Biscay, down to the present king and current holder of the title, Felipe VI of Spain.

| Tree of Lords of Biscay | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- José Ramón Prieto Lasa (2013), "La genealogía de los Haro en el Livro de Linhagens del Conde de Barcelos", Anuario de Estudios Medievales, 43/2: 833-69

- José Ramón Prieto Lasa (1991), "Las Leyendas de los Señores de Vizcaya y la Tradicion Melusiniana", doctoral dissertation, Complutense University of Madrid

- Juan Antonio Llorente, Noticias históricas de las tres provincias vascongadas en que se procura investigar el estado civil antiguo de Álava, Guipúzcoa y Vizcaya, y el origen de sus fueros (1808), vol. 5, pp. 429, 441, 486-7

- Monarquia de Espanña - Volumen1. Pedro Salazar de Mendoza, Gil González Dávila, Bartolomé Ulloa.

- Origen de las dignidades seglares de Castilla y Leon con relacion summaria. Pedro Salazar de Mendoza.

- Nobleza del Andalucia. Gonzalo Argote de Molina.

- Epitome de los señores de vizcaya. Recogida por Antonio Nauarro de. Antonio Navarro de Larreategui. 1620. p. 42.

Zeno, señor de Vizcaya toda.

- "Bizkaia y el Señorío" (PDF). Website of the Bizkaia Government. Diputación Foral de Bizkaia. Retrieved June 23, 2013.

- Historia General del País Vasco, Manuel Montero, Txertoa, Andoin, 2008, pag. 149

- Historia General del País Vasco, Manuel Montero, Txertoa, Andoin, 2008, pag. 150

- Historia General del País Vasco, Manuel Montero, Txertoa, Andoin, 2008, pag. 151

Further reading

- Balparda y las Herrerías, Gregorio de (1933–34). Historia crítica de Vizcaya y de sus Fueros. II, Libro III. El primer fuero de Vizcaya , el de los Señores. Bilbao: Imprenta Mayli. OCLC 634212337.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Martín Duque, Ángel J. (2002). "Vasconia en la alta edad media: somera aproximación histórica". Príncipe de Viana (in Spanish). Pamplona: Gobierno de Navarra: Institución Príncipe de Viana (227): 871–908. ISSN 0032-8472.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Salazar y Acha, Jaime de (1985). Una Familia de la Alta Edad Media: Los Velas y su Realidad Histórica. Asociación Española de Estudios Genealógicos y Heráldicos. ISBN 84-398-3591-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)