Lolita fashion

Lolita fashion (ロリータ・ファッション, rorīta fasshon) is a subculture from Japan that is highly influenced by Victorian clothing and styles from the Rococo period.[1][2][3][4][5][6] A very distinctive property of Lolita fashion is the aesthetic of cuteness.[7] This clothing subculture can be categorized into three main substyles: 'gothic', 'classic', and 'sweet'.[3][8][9][10][11] Many other substyles such as 'sailor', 'country', 'hime' (princess), 'ero' (erotic), 'guro' (grotesque), 'oriental', 'punk', 'shiro (white)', kuro (black) and steampunk lolita also exist. This style evolved into a widely followed subculture in Japan and other countries in the 1990s and 2000s[12][13][14][15][16] and may have waned in Japan as of the 2010s as the fashion became more mainstream.[17][18][19]

.jpg)

Description

The main feature of Lolita fashion is the volume of the skirt, created by wearing a petticoat or crinoline.[20][21][22] The skirt can be either bell-shaped or Aline-shaped.[22] Components of the lolita wardrobe consist mainly of a blouse (long or short sleeves) with a skirt or a dress, which usually comes to the knees. Lolitas frequently wear wigs in combination with other headwear such as hair bows or a bonnet (similar to a Poke bonnet). Lolitas can also wear Victorian style drawers under their petticoats. For further effect some Lolitas use knee socks, ankle socks or tights together with either high heels or flat shoes with a bow are worn. Other typical Lolita garments are a jumperskirt (JSK) and one-piece (OP).[23]

History

Although the origin of the fashion is unclear, at the end of the 1970s a new movement known as Otome-kei was founded, which slightly influenced Lolita fashion since Otome means maiden and maiden style looks like a lesser elaborated Lolita style.[20] Before Otome-kei emerged, there was already a rise of the cuteness culture in the earlier seventies; during which there was a high emphasis on cute and childish handwriting in Japanese schools.[24][25][26] As a result of that the company Sanrio began experimenting with cute designs.[27] The cuteness style, known as kawaii style, became popular in the 1980s.[28][29] After Otome-kei, Do-It-Yourself behavior became popular, which led to the emergence of a new style called 'doll-kei', the predecessor of Lolita fashion.[30]

In the years of 1977–1998, a large part of the Harajuku shopping district closed for car traffic on Sundays. The result was an increase in interaction between pedestrians in Harajuku.[31] When brands like Pink House (1973),[12][32] Milk (1970),[12] and Angelic Pretty (1979)[33] began to sell cute clothing, that resulted in a new style, which would later be known as 'Lolita'.[34] The term lolita first appeared in the fashion magazine Ryukou Tsushin in the September 1987 issue.[12] Shortly after that Baby, The Stars Shine Bright (1988),[35] Metamorphose temps de fille (1993),[36] and other brands emerged.[12] In the 1990s, lolita became more accepted, with visual kei bands like Malice Mizer and others rising in popularity. These band members wore elaborate clothes that fans began to adopt.[35] During this time Japan went through an economic depression,[37] leading to an increase in alternative youth and fashion cultures such as gyaru, otaku, visual kei, and lolita,[35] as well as visualkei inspired clothing such as Mori, Fairy Kei and Decora[38] The lolita style spread quickly from the Kansai region and finally reached Tokyo, partly due to the economic difficulties there was a big growth in the cuteness and youth cultures that originated in the seventies.[35] In the late nineties, the Jingu Bashi (also called the Harajuku Bridge) became known as meeting place for youth who wore lolita and other alternative fashion,[12][39][40][41] and lolita became more popular causing a spurt of lolita Fashion selling warehouses.[42] Important magazines that contributed to the spread of the fashion style were the Gothic & Lolita Bible (2001), a spin-off of the popular Japanese fashion magazine KERA (1998), and FRUiTS (1997).[43][44] It was around this time when interest and awareness of Lolita Fashion began entering countries outside of Japan, with The Gothic & Lolita Bible being translated into English, distributed outside of Japan through the publisher Tokyopop,[45][46] and FRUits publishing an English picture book of the Japanese Street Fashion in 2001. As the style became further popularized through the Internet, more shops opened abroad, such as Baby, The Stars Shine Bright in Paris (2007)[16] and in New York (2014).[47]

Over time, the youth that gathered in Harajuku or at Harajuku Bridge disappeared. One possible explanation is that the introduction of fast fashion from retailers H&M and Forever 21 has caused a reduction in the consumption of street fashion.[48][18] FRUiTS ceased publication while Gothic & Lolita Bible was put on hiatus in 2017.[48][49]

Sources of inspiration

Western culture has influenced Lolita fashion. The book Alice in Wonderland (1865),[50][51] written by Lewis Carroll,[52][53] has inspired many different brands and magazines,[35] such as Alice Deco.[52] The reason that the character Alice was an inspiration source for the Lolita, was because she was an ideal icon for the Shōjo (shoujo)-image,[35][54] meaning an image of eternal innocence and beauty.[55] The first complete translation of the book was published by Maruyama Eikon in 1910, translated under the title Ai-chan No Yume Monogatari (Fantastic stories of Ai).[56] Another figure from the Rococo that served as a source of inspiration was Marie Antoinette;[57] a manga The Rose of Versailles (Lady Oscar) based on her court, was created in 1979.

Popularization

People who have popularized the Lolita fashion were Yukari Tamura, Mana and Novala Takemoto. Novala wrote the light novel Kamikaze Girls (2002)[13][58] about the relationship between Momoko, a lolita girl and Ichigo, a Yanki. The book was adapted into a movie[13][59][60][61][62] and a manga in 2004. Novala himself claims that "There are no leaders within the lolita world".[63] Mana is a musician and is known for popularizing the Gothic Lolita fashion.[5] He played in the rock band Malice Mizer (1992–2001) and founded the heavy metal band Moi Dix Mois (2002–present). Both bands are a part of the visual kei movement, whose members are known for eccentric expressions and elaborate costumes. He founded his own fashion label, known as Moi-même-Moitié in 1999, which specializes in Gothic Lolita.[64][65][66][67] They are both very interested in the Roccoco period.[64]

The government of Japan has also tried to popularize Lolita fashion. The Minister of Foreign Affairs in February 2009,[68] assigned models to spread Japanese pop culture.[69][70][71][25] These people were given the title of Kawaa Taishi (ambassadors of cuteness).[70][35] The first three ambassadors of cuteness were model Misako Aoki, who represents the Lolita style of frills-and-lace, Yu Kimura who represents the Harajuku style, and Shizuka Fujioka who represents the school-uniform-styled fashion.[70][72] Another way that Japan tries to popularize Japanese street fashion and Lolita is by organizing the international Harajuku walk in Japan, this should caused that other foreign countries would organize a similar walk.[73]

Possible reasons for the popularity of Lolita fashion outside of Japan are a big growth in the interest of Japanese culture and use of the internet as a place to share information,[39][71][39][74][75] leading to an increase in worldwide shopping, and the opportunity of enthusiastic foreign Lolitas to purchase fashion.[76] The origin of the Japanese influences can be found in the late nineties, in which cultural goods such as Hello Kitty, Pokémon,[77] and translated mangas appeared in the west.[78] Anime was already being imported to the west in the early nineties,[79] and scholars also mention that anime and manga caused the popularity of Japanese culture to rise.[38][80] This is supported by the idea that cultural streams have been going from Japan to the west, and from the west to Japan.[81]

Motives

Lolita is seen as a reaction against stifling Japanese society, in which young people are pressured to strictly adhere to gender roles and the expectations and responsibilities that are part of these roles.[82][83][84][85][86] Wearing fashion inspired by childhood clothing is a reaction against this.[87][83][88][89] This can be explained from two perspectives. Firstly, that it is a way to escape adulthood[20][64][90][91][92][93] and to go back to the eternal beauty of childhood.[94][95] Secondly, that it is an escape to a fantasy world, in which an ideal identity can be created that would not be acceptable in daily life.[5][96][97]

Some Lolitas say they enjoy the dress of the subculture simply because it is fun and not as a protest against traditional Japanese society.[12] Other motives could be that wearing the fashion style increases their self-confidence[98][99][100][101] or to express an alternative identity.[12][76][33][97][102][103]

Social-economical dimension

Much of the very early lolitas in the 1990s hand-made most of their clothing, and were inspired by the Dolly Kei movement of the previous decade.[32] Because of the diffusion of fashion magazines people were able to use lolita patterns to make their own clothing. Another way to own lolita was to buy it second-hand.[104] The do-it-yourself behaviour can be seen more frequently by people who cannot afford the expensive brands.[105]

Because more retails stores were selling lolita fashion the do-it-yourself behaviour became less important. Partly due to the rise of e-commerce and globalization, lolita clothing became more widely accessible with the help of the Internet. The market was quickly divided into multiple components: one which purchases mainly from Japanese or Chinese internet marketplaces, the other making use of shopping services to purchase Japanese brands,[76] with some communities making larger orders as a group.[106] Not every online shop delivers quality lolita (inspired) products, a notorious example is Milanoo (2014).[107] with some web shops selling brand replicas, a frowned upon behaviour from many in this community.[108] A Chinese replica manufacturer that is famous for his replica design is Oo Jia.[108] Second-hand shopping is also an alternative to buying new pieces as items can be bought at a lower price (albeit with varying item condition) and is the sole method of obtaining pieces that are no longer produced by their respective brand.

Social-cultural dimension

Many lolitas consider being photographed without permission to be rude and disrespectful,[109][110][111] however some rules differ or overlap in different parts of this community.[112] Lolitas often host meetings in public spaces such as parks, restaurants, cafes, shopping malls, public events, and festivals.[113] Some meetings take place at members' homes, and often have custom house rules (e.g. each member must bring their own cupcake to the meeting).[114] Lolita meetings therefore are a social aspect of the lolita fashion community, serving as an opportunity for members to meet one another. Many lolitas also used to use Livejournal to communicate, but many have switched to Facebook groups in the interim.[115]

Confusions

Lolita fashion did not emerge until after the publication of the novel Lolita (1955),[76][116] which was written by Vladimir Nabokov, the first translation of the novel in Japanese appearing in 1959.[55] The novel is about a middle-aged man, Humbert Humbert, who grooms and abuses a twelve-year-old girl nicknamed Lolita.[117][118][119] Because the book focused on the controversial subject of pedophilia and underage sexuality, lolita soon developed a negative connotation referring to a girl inappropriately sexualized at a very young age[120] and associated with unacceptable sexual obsession.[121]

Lolita was made into a movie in 1962, which was sexualized and did not show the disinterest that Lolita had in sexuality.[122][123] A remake was made in 1997. The 17-year-old Amy Fisher, who attempted to murder the wife of her 35-year-old lover and whose crime was made into a film called The Amy Fisher Story (1993), was often called the Long Island Lolita. These films reinforced the sexual association.[124] Other racy connotations were created by Lolita Nylon advertisements (1964)[125] and other media that used Lolita in sexual contexts.[126] Another factor is that Western culture considers wearing cute clothing when adult to be childish, associating lolita with paedophile fantasies. In contrast, it is more acceptable for cuteness to be part of fashion in Japan.[126]

The Lolita complex (also known as Lolicon in writing about Lolita in sexual context),[127][128] was a term used by Russel Trainer in his novel The Lolita Complex (1966). This term became popular within the otaku culture.[6] and refers to paedophile desires.[6] This expression of the Lolita complex can be found back in the nineties when school uniforms became a central object of desire and young girls were pictured as sexual in manga.[129]

Within Japanese culture the name refers to cuteness and elegance rather than to sexual attractiveness.[130][131] Many lolitas in Japan are not aware that lolita is associated with Nabokov's book and they are disgusted by it when they discover such relation.[132]

Another confusion that often occurs is between the Lolita fashion style and cosplay. Although both spread from Japan, they are different and should be perceived as independent from each other;[133] one is a fashion style while the other is role-play, with clothing and accessory being used to play a character. This does not exclude that there may be some overlap between members of both groups.[134] This can be seen at anime conventions such as the convention in Götenborg in which cosplay and Japanese fashion is mixed.[135] For some Lolitas, it is insulting if people label their outfit as a costume.[12][136]

Gallery

.jpg) Hime Lolita (Misako Aoki)

Hime Lolita (Misako Aoki) Classic Lolita

Classic Lolita Old School Lolita

Old School Lolita Shiro/White Lolita (left) and Kuro/Black Lolita (right)

Shiro/White Lolita (left) and Kuro/Black Lolita (right) Sweet Lolita' (Nana Kitade)

Sweet Lolita' (Nana Kitade) Sweet Lolita

Sweet Lolita Sweet Lolita

Sweet Lolita Country Lolita (Nana Kitade)

Country Lolita (Nana Kitade)- Pirate Lolita

- Punk Lolita

- Wa-Lolita with characteristics of Guro Lolita (eyepatch)

.jpg) Dandy and Kodona

Dandy and Kodona.jpg) Sweet Lolita

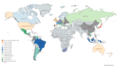

Sweet Lolita Lolita Fashion Spread in 2019

Lolita Fashion Spread in 2019 Lolita Fashion Spread Timelined on Livejournal

Lolita Fashion Spread Timelined on Livejournal

See also

Notes

- Hardy Bernal 2011, p. 20

- Monden 2008

- Robinson 2014, p. 9

- Gatlin 2014, p. 16

- Haijima 2013, p. 32

- Coombes 2016, p. 36

- Monden 2008, p. 29

- Style Spotlight: Gothic Lolita in Belgian Cupcakes Magazine, published by Hilde Heyvaert, vol. 5, 2012.

- Style Spotlight: Classic Lolita in Belgian Cupcakes Magazine, published by Hilde Heyvaert, vol. 2, 2011.

- Style Spotlight: Sweet Lolita in Belgian Cupcakes Magazine, published by Hilde Heyvaert, vol. 1, 2011.

- Berry 2017, p. 9

- Kawamura, Yuniya (2012). "Harajuku: The Youth in Silent Rebellion". Fashioning Japanese Subcultures. doi:10.2752/9781474235327/KAWAMURA0008. ISBN 9781474235327.

- Haijima 2013, p. 33

- Staite 2012, p. 75

- Robinson 2014, p. 53

- Monden 2008, p. 30

- "The Outrageous Street-Style Tribes of Harajuku". BBC. Retrieved 13 June 2018.

- "Japan's wild, creative Harajuku street style is dead. Long live Uniqlo". Quartz. Archived from the original on 8 August 2017. Retrieved 8 August 2017.

- "What the Hell has Happened to Tokyo's Fashion Subcultures?". Dazed. 4 December 2015. Retrieved 13 June 2018.

- Valdimarsdótti 2015, p. 21

- Hardy Bernal 2011, p. 23

- Robinson 2014, p. 39

- Gatlin 2014, p. 79

- Coombes 2016, p. 28

- Koma, K. (2013). "Kawaii as Represented in Scientific Research: The Possibilities of Kawaii Cultural Studies". Hemispheres, Studies on Cultures and Societies (28): 103–117.

- Christopherson 2014, p. 5

- Coombes 2016, p. 29

- Valdimarsdótti 2015, p. 29

- Onohara 2011, p. 35

- Hardy Bernal 2011, pp. 119–121

- Valdimarsdótti 2015, p. 13

- Hardy Bernal 2011, p. 119

- Christopherson 2014, p. 24

- Coombes 2016, p. 35

- Atkinson, Leia (2015). Down the Rabbit Hole: An Exploration of Japanese Lolita Fashion (Thesis). University of Ottawa. doi:10.20381/ruor-4249. hdl:10393/32560.

- "About Metamorphose". Metamorphose. Archived from the original on 23 September 2004. Retrieved 25 February 2018.

- Hardy Bernal 2011, p. 168

- Gatlin 2014, pp. 37, 61

- Kawamura, Yuniya (2006). "Japanese Teens as Producers of Street Fashion". Current Sociology. 54 (5): 784–801. doi:10.1177/0011392106066816.

- Kawamura, Yuniya (2012). "Geographically and Stylistically Defined Japanese Subcultures". Fashioning Japanese Subcultures. doi:10.2752/9781474235327/KAWAMURA0006a. ISBN 9781474235327.

- Gagné, Isaac (2008). "Urban Princesses: Performance and "Women's Language" in Japan's Gothic/Lolita Subculture". Journal of Linguistic Anthropology. 18: 130–150. doi:10.1111/j.1548-1395.2008.00006.x.

- "Tokyo Day 7 Part 3 — Gothic Lolita, Marui One, Marui Young Shinjuku". Retrieved 8 August 2017.

- "Pretty in Pink". The Bold Italic Editors. 8 April 2010. Archived from the original on 8 August 2017. Retrieved 9 August 2017.

- Onohara 2011, p. 33

- "Interview: Jenna Winterberg and Michelle Nguyen - Page 1, Aoki, Deb". Manga About. Archived from the original on 30 March 2008. Retrieved 11 February 2018.

- "Gothic & Lolita Bible in English". Japanese Streets. Archived from the original on 8 August 2017. Retrieved 8 August 2017.

- "Baby, the Stars Shine Bright and Tokyo Rebel to open retail locations in New York". Arama! Japan. July 2014. Archived from the original on 8 August 2017. Retrieved 8 August 2017.

- "Fashion Magazine KERA to End Print Publication". Arama! Japan. 30 March 2017. Archived from the original on 8 August 2017. Retrieved 8 August 2017.

- "What the Closure of FRUiTS Magazine Means for Japanese Street Style". Vice. 6 February 2017. Retrieved 13 June 2018.

- Coombes 2016, pp. 33, 37

- Hardy Bernal 2011, p. 199

- Younker 2011, p. 106

- Coombes 2016, p. 7

- Monden, Masafumi (2014). "Being Alice in Japan: Performing a cute, 'girlish' revolt". Japan Forum. 26 (2): 265–285. doi:10.1080/09555803.2014.900511.

- Hinton 2013, p. 1589

- Coombes 2016, p. 45

- Younker 2011, p. 103

- Staite 2012, p. 51

- Gatlin 2014, p. 29

- Coombes 2016, p. 31

- Staite 2012, p. 53

- Monden 2008, p. 25

- Hardy Bernal 2007, p. 3

- Hardy Bernal 2007

- Hardy Bernal 2011, pp. 72–73

- Coombes 2016, p. 39

- Valdimarsdótti 2015, p. 22

- "Press Conference, 26 February 2009". Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan. Archived from the original on 12 August 2017. Retrieved 12 August 2017.

- "Association formed to pitch 'Lolita fashion' to the world". The Japan Times Online. The Japan Times. 31 May 2013. Archived from the original on 11 August 2017. Retrieved 11 August 2017.

- Borggreen, G. (2013). "Cute and Cool in Contemporary Japanese Visual Arts". The Copenhagen Journal of Asian Studies. 29 (1): 39–60. doi:10.22439/cjas.v29i1.4020.

- Kawamura, Yuniya (2012). "The Globalization of Japanese Subcultures and Fashion: Future Possibilities and Limitations". Fashioning Japanese Subcultures. doi:10.2752/9781474235327/KAWAMURA0015. ISBN 9781474235327.

- "The Kawaii Ambassadors (Ambassadors of Cuteness)". Trends in Japan. Archived from the original on 11 August 2017. Retrieved 11 August 2017.

- Gatlin 2014, p. 66

- Valdimarsdótti 2015, p. 32

- Mikami 2011, p. 46

- Kang, Z. Young; Cassidy, T. Diane (2015). "Lolita Fashion: A transglobal subculture". Fashion, Style & Popular Culture. 2 (3): 371–384. doi:10.1386/fspc.2.3.371_1.

- Mikami 2011, p. 34

- Mikami 2011

- Plevíková 2017, p. 106

- Mikami 2011, pp. 46–55

- Hardy Bernal 2011, pp. 75–118

- Hinton 2013

- Younker 2011, p. 100

- Talmadge, Eric (7 August 2008). "Tokyo's Lolita scene all about escapismn". The Japan Times Online. The Japan Times. Archived from the original on 11 August 2017. Retrieved 11 August 2017.

- "Resistance and Self-Expression: Fashion's Power in Times of Difference". www.notjustalabel.com. Retrieved 3 May 2020.

- "Fashion As Resistance: The Everyday Rebellion". HuffPost. 16 February 2017. Retrieved 3 May 2020.

- Thomas, Samuel (2 July 2013). "Let's talk 100 percent kawaii!". The Japan Times Online. The Japan Times. Archived from the original on 6 August 2017. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- Robinson 2014

- Hardy Bernal 2011, p. 185

- Hardy Bernal 2011, p. 51

- Park, J. Joohee (2010). "Japanese Youth Subcultures Styles of the 2000s". International Journal of Costume and Fashion. 10 (1): 1–13. doi:10.7233/ijcf.2010.10.1.001.

- Staite 2012, pp. 10–12

- Mikami 2011, p. 64

- Hinton 2013, p. 1598

- Younker 2011, pp. 100, 106

- Peirson-Smith 2015

- Rahman, Osmud; Wing-Sun, Liu; Lam, Elita; Mong-Tai, Chan (2011). ""Lolita": Imaginative Self and Elusive Consumption". Fashion Theory. 15: 7–27. doi:10.2752/175174111X12858453158066.

- Haijima 2013, p. 40

- Kawamura, Yuniya (2012). "Individual and Institutional Networks within a Subcultural System: Efforts to Validate and Valorize New Tastes in Fashion". Fashioning Japanese Subcultures. doi:10.2752/9781474235327/KAWAMURA0012. ISBN 9781474235327.

- Berry 2017, p. 55

- Sugar Coated - A short documentary about Lolita Fashion, retrieved 3 May 2020

- Staite 2012, pp. 81–86

- Mikami 2011, pp. 62–63

- Robinson 2014, p. 47

- Staite 2012, p. 69

- Robinson 2014, p. 38

- Robinson 2014, p. 61

- Gatlin 2014, p. 93

- Robinson 2014, p. 85

- Gatlin 2014, pp. 104–107

- Hardy Bernal 2011, p. 221

- Robinson 2014, p. 57

- Gatlin 2014, pp. 103–104

- Gatlin 2014, p. 68

- Gatlin 2014, pp. 70–72

- Christopherson 2014, p. 23

- Hinton 2013, p. 1584

- Robinson 2014, p. 28

- Gatlin 2014, p. 67

- Hinton 2013, p. 1585

- Robinson 2014, p. 30

- Hinton 2013, pp. 1584–1585

- "Lolita Fashion". The Paris Review. 25 May 2017. Archived from the original on 6 August 2017. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- Hinton 2013, pp. 1586–1587

- "Lolita Nylon Advertisements". Archived from the original on 10 July 2016. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- Monden 2008, p. 34

- Coombes 2016, p. 33

- Hinton 2013, p. 1593

- Kinsella, Sharon (2002). "What's Behind the Fetishism of Japanese School Uniforms?". Fashion Theory. 6 (2): 215–237. doi:10.2752/136270402778869046.

- Peirson-Smith 2015, p. 10

- Tidwell, Christy (2010). Street and Youth Fashion in Japan. 6. doi:10.2752/BEWDF/EDch6063. ISBN 9781847888556.

- https://doi.org/10.1017/S0040557418000522 Michelle Liu Carriger (2019) “Maiden's Armor”: Global Gothic Lolita Fashion Communities and Technologies of Girly Counteridentity. Theatre Survey. Volume 60(1), 122-146, p. 131.

- Staite 2012, p. 2

- De opkomst van de mangacultuur in België. Een subcultuuronderzoek., Lora-Elly Vannieuwenhuysen, p. 48, KU Leuven, 2014-2015.

- Mikami 2011, pp. 5–12

- Gatlin 2014, p. 30

References

- Berry, B. (2017). Ethnographic Comparison of a Niche Fashion Group, Lolita (Thesis). Florida Atlantic University.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Christopherson, M. (2014). The Power of Cute: Redefining Kawaii Culture As a Feminist Movement (Thesis). Carthage College.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Coombes, K. (2016). Consuming Hello Kitty: Saccharide Cuteness in Japanese Society (Thesis). Wellesley College.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gatlin, Chancy J. (2014). The Fashion of Frill: The Art of Impression Management in the Atlanta Lolita and Japanese Street Fashion Community (Thesis). Georgia State University.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Haijima, A. (2013). Japanese Popular Culture in Latvia: Lolita and Mori Fashion (Thesis). University of Latvia.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hardy Bernal, Kathryn A. (2007). Kamikaze Girls and Loli-Goths. Fashion in Fiction Conference, University of Technology, Sydney, Australia. Archived from the original on 11 August 2017. Retrieved 11 February 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hardy Bernal, Kathryn Adele (2011). The Lolita Complex: A Japanese fashion subculture and its paradoxes (Thesis). Auckland University of Technology. p. 20. hdl:10292/2448.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hinton, Perry R. (2013). "Returning in a Different Fashion: Culture, Communication, and Changing Representations of Lolita in Japan and the West". International Journal of Communication. 7: 1582–1602.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mikami, K. (2011). Cultural Globalization in People's Life Experiences: Japanese Popular Cultural Styles in Sweden (Thesis). Stockholm University.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Monden, Masafumi (2008). "Transcultural Flow of Demure Aesthetics: Examining Cultural Globalisation through Gothic & Lolita Fashion, The Japan Foundation Sydney". New Voices. 2: 21–40. doi:10.21159/nv.02.02.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Onohara, N. (2011). "Japan as fashion: Contemporary reflections on being fashionable". Acta Orientalia Vilnensia. 12 (1): 29–41. doi:10.15388/AOV.2011.0.1095.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Peirson-Smith, A. (2015). Hey sister, can I borrow your style?: a study of the trans-cultural, trans-textual flows of the Gothic Lolita trend in Asia and beyond (Thesis). City University of Hong Kong.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Plevíková, I. (2017). Lolita: A Cultural Analysis (Thesis). Masarykova Univerzita.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Robinson, K. (2014). Empowered Princesses: An Ethnographic Examination of the Practices, Rituals, and Conflicts within Lolita Fashion Communities in the United States (Thesis). Georgia State University.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Staite, S. Abigail (2012). Lolita: Atemporal Class-Play With tea and cakes (Thesis). University of Tasmania.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Valdimarsdótti, I. Guðlaug (2015). Fashion Subcultures in Japan. A multilayered history of street fashion in Japan (Thesis). University of Iceland.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Younker, T. (2011). "Lolita: Dreaming, Despairing, Defying". Stanford Journal of East Asian Affairs. 11 (1): 97–110.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading and documentaries

- Lolitas Of Amsterdam | Style Out There | Refinery29 (documentary) at YouTube

- Lolita Fashion documentaries (documentaires) playlist at YouTube

- List of Lolita brands at Tumblr (archived version at archive, 14 augustus 2017 version)

- Rebels in Frills: a Literature Review on Lolita Subculture at Academia (thesis) from South Carolina Honors College

- Shoichi Aoki Interview (2003) founder of the street fashion magazine FRUiTS at ABC Australia (archived version at archive, 14 August 2017 version)

- The Tea Party Club's 5th Anniversary starring Juliette et Justine: Q&A (2012) at Jame World (archived version at archive, 14 August 2017 version)

- Innocent World Tea Party in Vienna: Q&A (2013) at Jame World (archived version at archive, 14 August 2017 version)

- The Tea Party Club Presents: Revelry Q&A (2014) at Jame World (archived version at archive, 14 August 2017 version)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lolita fashion. |