Liverpool Overhead Railway

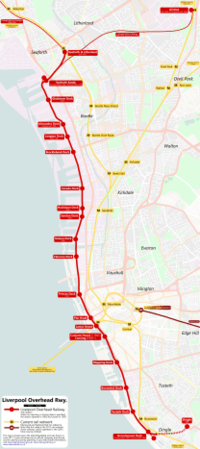

The Liverpool Overhead Railway (known locally as the Dockers' Umbrella) was an overhead railway in Liverpool which operated along the Liverpool Docks and opened in 1893 with lightweight electric multiple units. The railway had a number of world firsts: it was the first electric elevated railway, the first to use automatic signalling, electric colour light signals and electric multiple units,[1] and was home to one of the first passenger escalators at a railway station.[2] It was the second oldest electric metro in the world, being preceded by the 1890 City and South London Railway.

| Liverpool Overhead Railway | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Overview | |||

| Other name(s) | Dockers' Umbrella | ||

| Type | Elevated railway | ||

| Operation | |||

| Opened | 6 March 1893 | ||

| Closed | 30 December 1956 | ||

| Operator(s) | Liverpool Overhead Railway Company | ||

| Events | |||

| Demolished | September 1957 - January 1958 | ||

| Technical | |||

| Line length | 7 mi (11 km) | ||

| Number of tracks | 2 | ||

| Track gauge | 1,435 mm (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in) standard gauge | ||

| |||

Originally spanning five miles from Alexandra Dock to Herculaneum Dock, the railway was extended at both ends over the years of operation, as far south as Dingle and north to Seaforth & Litherland. A number of stations opened and closed during the railway's operation owing to relative popularity and damage, including air bombing during World War II. At its peak almost 20 million people used the railway every year.[3] Being a local railway, it was not nationalised in 1948.

In 1955, a report into the structure of the many viaducts showed major repairs were needed that the company could not afford. The railway closed at the end of 1956 and despite public protests the structures were dismantled in the following year.

Since 1977, Liverpool's rapid transit/commuter rail needs have been served by the partly underground Merseyrail network, which was formed from local suburban lines and uses no former infrastructure of the Liverpool Overhead Railway.

History

Toponymy

The overhead refers to the railway being primarily constructed above street level, and not to overhead line, though there is no ambiguity as the electrical supply was third rail. When the LOR was extended to the Dingle terminus the overhead description of the railway would have seemed an anomaly to those descending to the platform there which was underground in a tunnel. At least two alternative names for the railway existed: Dockers’ Umbrella; and ovee,[lower-alpha 1] a local slang term.[4]

Origins and construction

Liverpool Overhead Railway | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

As a result of the traffic, congestion, and overcrowding of the dock roads, many proposals were made for transport solutions.[5] Rails were laid at Liverpool Docks in 1852, linking the warehouses and docks. Initially horses were used, as locomotives were banned because of the risk of fire.[6] From 1859, passenger services were provided using adapted horse omnibuses; the wheel flanges could be retracted to allow an omnibus to leave the tracks to overtake a goods train. By the 1880s, there was an omnibus service every five minutes.[7]

An elevated railway was first proposed in 1852, and in 1878 the Mersey Docks and Harbour Board (MD&HB) obtained powers for a single-line steam railway with passing loops at stations. The MD&HB applied to the Board of Trade based on this plan, but it was rejected and there was no further progress.[8][2] The Liverpool Overhead Railway Company was formed in 1888 and obtained permission to build a double-track railway in the same year.[9]

Engineers Sir Douglas Fox and James Henry Greathead were commissioned to design the railway.[10] Steam traction was considered and they considered fitting floors to the structure to prevent ash falling to the street below, however this was seen as a fire risk. Sir William Forwood, the Chairman of the Liverpool Overhead Railway, had studied American electric railways, and in 1891 electric traction was chosen.[9][11] John William Willans was chosen as the primary contractor.[12] Building started in 1889 and was completed in January 1893.[13][14]

The structure was to be made of wrought iron girders a nominal 16 ft (4.9 m) above the roadway. A total of 567 spans were erected, most being 50 ft (15 m) long. The standard gauge railway was laid on longitudinal timbers on the elevated sections.

Four bridges were constructed to cross wider streets.[2] Hydraulic lifting sections were provided at Brunswick, Sandon and Langton Docks to allow goods access to the docks. To allow shipping access to the Leeds and Liverpool Canal, at Stanley Dock a bridge was replaced by a combined lifting and swing bridge, the lower lifting section carrying the road and goods railway.[10]

At Bramley-Moore Dock, the railway dropped to road level to pass under the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway (L&YR) coal tip branch. As the gradient was 1 in 40 this was known as the switchback.[15]

Originally the conductor rail was placed between the rails, energised at 500–525 volts DC. The power was supplied by a generating station at Bramley-Moore Dock that received its coal directly from the Lancashire & Yorkshire Railway branch line which passed above.[11][16] Special lightweight passenger cars were designed with each having a driving motor car; one bogie was powered with a single 60 horsepower (45 kW) motor.[17] They were placed on the track in the switchback section.[15]

The finished railway ran between Alexandra Dock and Herculaneum Dock, though the line extended another half a mile north of Alexandra Dock station to the carriage sheds and workshops; no land closer to the station had been available.[5] At the time of opening in February 1893, the railway had cost £510,000 and used a total of 25,000 tons of iron and steel.[18]

Opening

The Marquis of Salisbury at the opening ceremony.[18]

The first official journey on the railway took place on 7 January 1893, with the railway Chairman taking engineers and other people of importance on a tour of the length of the railway.[5] The railway was officially opened on 4 February the same year by the Leader of the Opposition the Marquis of Salisbury, who turned on the main electrical current during a ceremony at the generating station at the Bramley-Moore Dock.[18] The ceremony was attended by the Earl of Lathom, Lord Kelvin, the Mayor of Liverpool, the chairman of the Dock Board, directors and engineers, and a number of other guests, who traveled on an inaugural journey along the railway.[18]

The public services started on 6 March, with the first carriages leaving from the Alexandra Dock and Herculaneum Dock stations at 7am. The Liverpool Echo reported that "the carriages appear to be fairly well filled with passengers."[19] In the early days of the railway there were a number of injuries and at least one fatality as a result of passengers and conductors overestimating the height of the railway while standing up on the top deck of open top buses.[20]

Realising that the railway was receiving low traffic outside of working hours, the line was extended northwards to Seaforth Sands on 30 April 1894 in order to reach more residential areas.[14] The extension brought the total length of the railway to 6 miles and cost a total of £10,000.[21] While the passengers had previously been primarily travelling to businesses and the city, the Seaforth extension resulted in a large increase in traffic from residents of the outer areas of Liverpool.[22] An extension southwards from Herculaneum Dock to Dingle was opened on 21 December 1896. Dingle was the only underground station, the extension from Herculaneum Dock being achieved with a 200 ft (61 m) lattice girder bridge and a half-mile (800 m) tunnel through the sandstone cliff to Park Road.[23]

Operation

The railway's contractor, J.W. Willans was appointed as its Chief Engineer.[24] He specialised in building and running electric railways, and in 1902, newer and more powerful electric motors were fitted to the trains in order to reduce service times in order to keep up with the competition from trams.[17] In the early 20th century, the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway L&YR was electrifying its routes out of Liverpool Exchange. A connection was built from the L&YR Seaforth & Litherland station to a new station beside Seaforth Sands.

The railway became popular with tourists. A 1902 Liverpool guidebook devoted a whole chapter to viewing and visiting the docks via the overhead railway, and a 1930s poster described it as "the best way to see the finest docks in the world".[25] As of 1919, a total of 18 million passengers used the Overhead Railway each year,[26]14 million passengers per year, even during WWII, and 9 million into the 1950s.[27]

From 1902, the journey end-to-end journey time was reduced to 22 minutes, but due to increased power and maintenance costs, the trains were then slowed down by 6 minutes in 1908, and the frequency of trains was increased to one every 3 minutes during peak times. By 1910, the operating hours were unrivaled, providing at least one train every 10 minutes from 4:45 am until 11:33 pm on weekdays.[26]

From 2 July 1905, Overhead Railway trains began running through to Seaforth & Litherland, [28] and through connections and through bookings between Liverpool Overhead Railway stations and the Southport branch of the Lancashire & Yorkshire Railway were made available, with revised fares and timetables.[29] The L&YR built some special lightweight electric stock and from 1906 began running services from Dingle to Southport and Aintree.[28] Regular services to Aintree were withdrawn in 1908, and after this special trains ran only twice a year, on Jump Sunday and the following Friday for the Grand National, both held at Aintree Racecourse. Through services from Dingle to Southport were withdrawn in 1914.[30] By 1914 the railway had served over 10,000,000 passengers.[5]

To allow the through-running of L&YR trains, the conductor rail was moved to outside the running rails and the centre rail became the earth return until the 1920s.[31] The first automatic train-stop system was installed on the line, and was electrically operated. An arm on the trackside would be struck by each passing train, activating an electromagnet, resulting in a 'danger' signal being shown until the train had passed through the next station. As a result of automation, the number of manned signal boxes was reduced to two. The line upgraded the signalling from semaphore to a Westinghouse permanent daytime colour-light system in 1921: the first to be installed in Britain.[32] The track also contained automatic braking systems for trains which ran through a red light; the current could be automatically disconnected and air brakes applied.[33]

The seventeenth and final station was opened on 16 June 1930, at Gladstone Dock, between Alexandra Dock and Seaforth Sands stations.[34] Plans were put forward to extend the line from Herculaneum Dock to St Michaels, and from Seaforth Sands to Sefton, to create a circular route, using the Hunts Cross to Southport line, however, these were never carried out.[35]

With fewer ships docking in Liverpool during the Great Depression, there was a reduction in usage for the Overhead Railway. Tourist tickets were offered from 1932, which also included visits to ocean liners that were moored at the docks, as part of a scheme to increase ticket sales, along with reduced prices, and a major advertising campaign.[36]

During World War II, the railway suffered extensively from bomb damage. As a purely local undertaking, it was not nationalised in 1948 with the rest of the British railway system.[37] In the late 1940s and early 1950s, the company started to modernise some of the carriages, incorporating sliding doors. The line continued to carry large numbers of passengers, especially dock workers.

The Mersey Docks & Harbour Board maintained stringent controls over the operation of the Overhead Railway for the duration of its operation. The Board protected its own freight transport interests by including clauses in the Overhead Railway's enabling legislation to limit the weight of parcels that could be transported, and renewing the lease on it every seven years. The Board blocked an attempt by the Liverpool Overhead Railway Company to extend its line to join the Lancashire & Yorkshire Railway at Seaforth for the purposes of transporting coal to Herculaneum Dock. The lack of development or rescue by the Board was at least in part due to its determination to restrict its activities to those that directly impacted the dock.[38]

Closure

The railway was carried mainly on iron viaducts, with a corrugated iron decking onto which the tracks were laid. It was vulnerable to corrosion, especially as the steam-operated Docks Railway operated beneath some sections, despite the locomotives being fitted with chimney cowls which were intended to deflect the steam from the structure.[39] Parts of the decking had become rusty on the surface, caused by steam and soot from the dock locomotives that passed underneath, mixing with rainwater to form an acid that began to corrode the metalwork. Drainage blockages combined with grit and constant vibration also played a part in the degradation of the structure.

Alongside this deterioration of the railway, the company never made as much money as they had hoped. Passengers made shorter journeys over the years, with the average passenger value declining from 2d in 1897 to 1.7d in 1913. Electric trams were introduced and competed with the railway, reducing the number of people using it, and changes to ticketing increased operational costs for the company.[5]

A full-time maintenance team was employed solely for the Overhead Railway, but struggled to keep up with repairs, and costs began to rise steeply during the 1950s.[40] In 1955, a survey discovered that repairs would be necessary in five years at a cost of £2 million. The company could not afford such costs and looked for financial support, from the Liverpool Corporation, the Mersey Docks and Harbour Board and British Rail. A number of attempts to rescue the railway and arrange a takeover took place over the next year but were ultimately unsuccessful.[41][40][2]

The company went into voluntary liquidation, despite still being reporting to be profitable for its shareholders,[40] and was relieved of its statutory obligation to operate passenger services with the Liverpool Overhead Railway Act 1956.[38]

Despite public protest, the line was closed on the evening of 30 December 1956.[42] The final two scheduled trains were full of passengers and were timed to meet at Pier Head, where crowds gathered.[40] It was the first electrified urban railway in the UK to close.[37]

A small number of staff were kept to maintain the buildings and structures, and it was hoped that a way of reopening the railway could be found.[43] More than 100 members of the LOR staff joined British Railways for work after its closure.[43] The railway was replaced by a bus service operated by Liverpool Corporation who purchased 60 new buses for the route.[44] The price of a workman's return fare subsequently increased from 8d to 1s as workers were forced to use bus services.[38]

Demolition

Demolition of the structure commenced on 23 September 1957, and all 80 acres of elevated were removed by January the following year.[45]

Little evidence of the railway remains, but a small number of columns set into walls at Huskisson Dock, and the tunnel at Herculaneum Dock into Dingle station have survived, the latter being used as a garage.[46] The foundations of the double deck swing bridge at Stanley Dock also remain.[47]

One of the original wooden carriages, on a recreated section of elevated track, remains on display with other artefacts at the Museum of Liverpool,[48] and the only surviving First class modernised carriage, No 7, was taken on by Coventry Railway Centre.

On 24 July 2012 a portion of the terminal tunnel near Dingle collapsed.[49]

Rolling stock

_(14574158560).jpg)

The railway used electric units with passenger accommodation and an electric motor in the same unit. Any number could be coupled together with all motors controlled by the driver.[51] Built between 1892 and 1899 by Brown Marshall & Co, the original units had one 60 horsepower (45 kW) motor, but by the third batch this had been replaced by a 70 horsepower (52 kW) motor. In 1902 the motor cars were fitted with two 100 horsepower (75 kW) motors, and these were replaced in 1919 by 75 horsepower (56 kW) motors.[52] Air brakes were fitted, the pressure topped up at the termini.[53] In the early days a single motor coach ran off-peak, but the norm became a three-coach train consisting of two motor coaches with a trailer coach between.[17] Two classes of accommodation were provided, originally first and second, becoming first and third in 1905 when the L&YR began running over the railway.[54] The cars were open with transverse seating: the central trailer had leather-covered seats for first class passengers; third class passengers had wooden seating.[52] As the voltage was 500V, when they ran on the L&YR 630V system the motors had to be in series mode.[55]

In 1945-47 a three car train was modernised, replacing the timber body with aluminium and plywood and fitting power-operated sliding doors under control of the guard.[56] New trains were considered too expensive and six more trains were rebuilt.[57]

The Liverpool Overhead Railway operated one steam locomotive, called Lively Polly, an inside-cylinder 0-4-0WT, which was originally built in Leeds by Kitson for the West Lancashire Railway. It was used to deice the track and haul the maintenance train from its acquisition in the 1890s until it was sold to Rea Ltd, a coal merchant in Birkenhead in 1949. It was replaced by a Ruston diesel engine, which was bought in 1947. Both were fitted with the proprietary coupling used by the Overhead Railway's EMUs.[58]

An original train was kept by the Museum of Liverpool[59] and a modernised carriage is stored at the Electric Railway Museum, Warwickshire.[60]

Film

The railway is featured in the films Waterfront (1950) and The Magnet (1950), and in the final scenes of The Clouded Yellow (1951), as the character played by Jean Simmons uses it to travel to one of the docks. Extensive archive footage appears in Of Time and the City, a "cinematic autobiographical poem" made by British film-maker Terence Davies[61] to celebrate Liverpool's 2008 reign as Capital of Culture. In 1897, the Lumière brothers filmed Liverpool,[31][62] including what is believed to be the first tracking shot, taken from the railway.

See also

References

Notes

- The term ovee seems a fairly obvious derivation in Liverpool English (scouse).

Footnotes

- Liverpool Overhead Railway The Transport Trust

- Suggitt, Gordon (2004). Lost Railways of Merseyside & Greater Manchester. Irthlingborough: Countryside Books. pp. 26–31. ISBN 1853068691.

- Atkinson-James, Rachel (2014). Liverpool Dialect. Sheffield: Bradwell Books. p. 61. ISBN 9781909914247.

- Liverpool Echo (2013).

- Adrian Jarvis (1996). Portrait of the Liverpool Overhead Railway. Ian Allan Publishing. ISBN 0711024685.

- Gahan 1982, p. 11.

- Gahan 1982, p. 12.

- Gahan 1982, pp. 12-13.

- Gahan 1982, pp. 13-14.

- Gahan 1982, p. 19.

- Welbourn 2008, p. 19.

- "The Great Northern and City Railway Company". To-Day. 20 April 1895. p. 334.

- Gahan 1982, pp. 19-21.

- Bolger 2007, p. 7.

- Gahan 1982, p. 21.

- Gahan 1982, pp. 24-25, 34.

- Gahan 1982, p. 30.

- "Opening of the Overhead Railway". Liverpool Echo. 4 February 1893. p. 3.

- "The Overhead Railway: Opened for traffic". Liverpool Echo. 6 March 1893. p. 4.

- John Belchem (2006). Liverpool 800. Liverpool University Press. p. 269. ISBN 1846310342.

- "Extension of the Liverpool Overhead Railway". Liverpool Mercury. 30 April 1894. p. 5.

- John Haldane (1897). Railway engineering, mechanical and electrical. E. & F.N. Spon. pp. 498–509.

- Gahan 1982, p. 21-22.

- "WILLANS, JOHN BANCROFT (1881 - 1957), country landowner, antiquarian and philanthropist". Dictionary of Welsh Biography. The National Library of Wales. 2001.

- John Belchem (2006). Liverpool 800. Liverpool University Press. p. 278. ISBN 1846310342.

- Welbourn 2008, p. 24.

- Welbourn 2008, p. 31.

- Gahan 1982, p. 23.

- "The Liverpool Overhead Railway". Liverpool Echo. 1 July 1905. p. 4.

- Gahan 1982, pp. 23-24.

- Koeck, Richard (2010). "Liverpool Overhead Railway archive film footage". National Museums Liverpool. Retrieved 27 July 2013.

- Welbourn 2008, p. 7.

- Bolger 2007, p. 74.

- "New Liverpool Station". Liverpool Echo. 16 June 1930. p. 8.

- Welbourn 2008, p. 20.

- Welbourn 2008, p. 25.

- Welbourn 2008, p. 5.

- Ritchie-Noakes, Nancy (1984). Liverpool's Historic Waterfront: The World's First Mercantile Dock System. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office. p. 168. ISBN 0117011886.

- Welbourn 2008, p. 3.

- Welbourn 2008, p. 32.

- Gahan 1982, p. 69.

- Gahan 1982, p. 70.

- George Eglin (31 December 1956). "First Day Without Overhead". Liverpool Echo.

- "Floral tribute for the last Overhead train". Liverpool Daily Post. 31 December 1956. p. 1.

- Gahan 1982, p. 72.

- Bolger 2007, p. 8.

- Welbourn 2008, p. 34.

- "Liverpool Overhead Railway motor coach number 3, 1892 - Museum of Liverpool, Liverpool museums". www.liverpoolmuseums.org.uk. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- "Tunnel collapse on Park Road sees homes evacuated in Liverpool". Liverpool echo. 24 July 2012. Retrieved 24 July 2012.

- "The Street Railway Journal". archive.org. New York: McGraw Publishing Company. 19 July 1902 [1884]. Retrieved 14 April 2017.

- "Trial Running and Inspection (reprinted)". Manchester Weekly Times. 13 January 1893. Archived from the original on 17 July 2012. Retrieved 28 June 2012.

- Gahan 1982, pp. 29-30.

- "Accident at Dingle 20 December 1898" (PDF). Railways Archive. Board of Trade. 26 January 1899. Retrieved 28 June 2012.

- Gahan 1982, p. 29.

- Gahan 1982, p. 34.

- Gahan 1982, p. 31.

- Gahan 1982, p. 32.

- Welbourn 2008, p. 26.

- "Liverpool Overhead Railway motor coach number 3, 1892". Museum of Liverpool. Retrieved 28 June 2012.

- "Liverpool Overhead Railway Car No. 7". Baginton, Warwickshire: Suburban Electric Railway Association. Retrieved 26 April 2011.

- Fairclough, Damon (2008). "Clutching at moments". .noise heat power. Retrieved 27 July 2013.

- Alexandre Promio (1897). Liverpool Scenes. 1:27 minutes: Lumière brothers.CS1 maint: location (link)

Sources

- Liverpool Echo (8 May 2013) [2008]. "The Docker's Umbrella: End of the line". Liverpool Echo. Archived from the original on 15 August 2020. Retrieved 15 August 2020.

Bibliography

- Bolger, Paul (2007). The Docker's Umbrella: A History of Liverpool Overhead Railway. Liverpool: The Bluecoat Press. ISBN 978-1-872568-05-8.

- Gahan, John W. (1982). Seventeen Stations to Dingle. Birkenhead: Countrywise. ISBN 978-0-907768-20-3.

- Welbourn, Nigel (2008). Lost Lines: Liverpool and the Mersey. Hersham, Surrey: Ian Allan Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7110-3190-6.

Further reading

- Bolger, Paul (1996). Liverpool Overhead Railway. Liverpool: The Bluecoat Press. ISBN 978-1-872568-40-9.

- Box, Charles E. (1959). Liverpool Overhead Railway, 1893-1956. Railway World Ltd. OCLC 867799954.

- Royden, Mike (2017), 'Liverpool Overhead Railway' in Tales from the 'Pool, Creative Dreams, ISBN 978-0993552410

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Liverpool Overhead Railway. |