Least tern

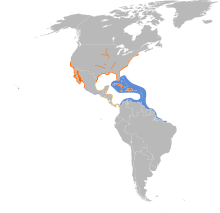

The least tern (Sternula antillarum) is a species of tern that breeds in North America and locally in northern South America. It is closely related to, and was formerly often considered conspecific with, the little tern of the Old World. Other close relatives include the yellow-billed tern and Peruvian tern, both from South America.

| Least tern | |

|---|---|

_RWD1.jpg) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Charadriiformes |

| Family: | Laridae |

| Genus: | Sternula |

| Species: | S. antillarum |

| Binomial name | |

| Sternula antillarum (Lesson, 1847) | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Sterna antillarum | |

It is a small tern, 22–24 cm (8.7–9.4 in) long, with a wingspan of 50 cm (20 in), and weighing 39–52 g (1.4–1.8 oz). The upper parts are a fairly uniform pale gray, and the underparts white. The head is white, with a black cap and line through the eye to the base of the bill, and a small white forehead patch above the bill; in winter, the white forehead is more extensive, with a smaller and less sharply defined black cap. The bill is yellow with a small black tip in summer, all blackish in winter. The legs are yellowish. The wings are mostly pale gray, but with conspicuous black markings on their outermost primaries. It flies over water with fast, jerky wingbeats and a distinctive hunchback appearance, with the bill pointing slightly downward.

It is migratory, wintering in Central America, the Caribbean and northern South America. Many spend their whole first year in their wintering area.[2] It has occurred as a vagrant to Europe, with one record in Great Britain.

It differs from the little tern mainly in that its rump and tail are gray, not white, and it has a different, more squeaking call; from the yellow-billed tern in being paler gray above and having a black tip to the bill; and from the Peruvian tern in being paler gray above and white (not pale gray) below and having a shorter black tip to the bill.

Subspecies

The differences among the three subspecies may not be as much as had been thought.[3][4]

- S. a. athalassos – (Burleigh & Lowery, 1942): Breeds on the rivers of the Arkansas River, Mississippi River, Brazos River, Trinity River, and Rio Grande basins;[2] winters south to northern Brazil.

- S. a. antillarum – (Lesson, 1847): nominate, Breeds on the Atlantic coast of North America, from Maine south along the east and south coasts of the United States, Bermuda, the Caribbean, and Venezuela; winters south to northern Brazil.

- S. a. browni – (Mearns, 1916): California least tern. Breeds on the Pacific coast of North America, from central California south to western Mexico; winters mainly in Central America.

- An unknown subspecies was found in 2012 nesting on the Big Island of Hawaii [5]

Conservation and status

S. a. antillarum

The population is about 21,500 pairs; it is not currently considered federally threatened, though it is considered threatened in many of the states in which it breeds. Threats include egg and fledgling predators, high tides and recreational use of nesting beaches.

S. a. athalassos

The interior subspecies, with a current population of about 7000 pairs, was listed as an endangered subspecies in 1985 (estimated 1000 breeding pairs), due to loss of habitat caused by dams, reservoirs, channelization, and other changes to river systems.

S. a. browni

The western population, the California least tern, was listed as an endangered species in 1972 with a population of about 600 pairs. With aggressive management, mainly by exclusion of humans via fencing, the Californian population has rebounded in recent years to about 4500 pairs, a marked increase from 582 pairs in 1974 when census work began, though it is still listed as an endangered subspecies.[3][4] The California subspecies breeds on beaches and bays of the Pacific Ocean within a very limited range of southern California, in San Francisco Bay and in northwestern Mexico. While numbers have gradually increased with its protected status, it is still vulnerable to predators, natural disasters or further disturbance by humans. Recent threats include the gull-billed tern (Sterna nilotica), which can decrease reproductive success in a colony to less than 10%.[6]

Nesting and breeding behavior

The least tern arrives at its breeding grounds in late April. The breeding colonies are not dense and may appear along either marine or estuarine shores, or on sandbar islands in large rivers, in areas free from humans or predators. Courtship typically takes place removed from the nesting colony site, usually on an exposed tidal flat or beach. Only after courtship has confirmed mate selection does nesting begin by mid-May and is usually complete by mid-June. Nests are situated on barren to sparsely vegetated places near water, normally on sandy or gravelly substrates. In the southeastern United States, many breeding sites are on white gravel rooftops.[7] In the San Francisco Bay region, breeding typically takes place on abandoned salt flats. Where the surface is hard, this species may use an artificial indentation (such as a deep dried footprint) to form the nest basin.

The nest density may be as low as several per acre, but in San Diego County, densities of 200 nests per acre have been observed. Most commonly the clutch size is two or three, but it is not rare to consist of either one or four eggs. Adults are known to wet themselves and shake off water over the eggs when arriving at the nest.[8] Both female and male incubate the eggs for a period of about three weeks, and both parents tend the semiprecocial young. Young birds can fly at age four weeks. After formation of the new families, groupings of birds may appear at lacustrine settings in proximity to the coast. Late-season nesting may be renests or the result of late arrivals. In any case, the bulk of the population has left the breeding grounds by the end of August.

Batiquitos Lagoon, a breeding site in San Diego County, California

Batiquitos Lagoon, a breeding site in San Diego County, California Nesting pair on the Missouri River in South Dakota

Nesting pair on the Missouri River in South Dakota- A least tern attacking a much larger black skimmer near Drum Inlet in North Carolina, United States.

_RWD3.jpg) Mating pair at Sunset Beach, North Carolina

Mating pair at Sunset Beach, North Carolina The mating sequence of a pair of least terns processed into one image. (St. Augustine, Florida)

The mating sequence of a pair of least terns processed into one image. (St. Augustine, Florida) This least tern is on the nest. There are two eggs which can be seen if one looks closely.

This least tern is on the nest. There are two eggs which can be seen if one looks closely. The eggs are speckled and generally blend well with the sandy surface.

The eggs are speckled and generally blend well with the sandy surface. A least tern lying just below the surface of the sand is probably on its nest. The nests are very shallow and minimally scooped out.

A least tern lying just below the surface of the sand is probably on its nest. The nests are very shallow and minimally scooped out. First fish feeding at Quintana, Texas

First fish feeding at Quintana, Texas Two-day-old chicks

Two-day-old chicks Seven-day-old chicks

Seven-day-old chicks- Least tern (S. a. antillarum) at Lake Jackson, Florida

Feeding and roosting characteristics

The least tern hunts primarily in shallow estuaries and lagoons, where smaller fishes are abundant. It hovers until spotting prey, and then plunges into the water without full submersion to extract meal. The most common prey recently for both chicks and adults are silversides smelt (Atherinops spp.) and anchovy (Anchoa spp.) in southern California,[9] as well as shiner perch, and small crustaceans elsewhere. Adults in southern California eat kelpfish (most likely giant kelpfish, Heterostichus rostratus).[9] Insects are known to be eaten during El Niño events.[10][11] In southern California, least terns feed in bays and lagoons, near shore, and more than 24 km (15 mi) from shore in the open ocean.[9] Elsewhere, they feed in proximity to lagoons or bay mouths.

Adults do not require cover, so that they commonly roost and nest on the open ground. After young chicks are three days old, they are brooded less frequently by parents and require wind blocks and shade, and protection from predators. In some colonies in southern California, Spanish roof tiles are placed in colonies so chicks can hide there. Notable disruption of colonies can occur from predation by burrowing owls, gull-billed terns and American kestrels.[12] Depredation by domestic cats has been observed in at least one colony.[13] Predation on inland breeding terns by coyotes, bobcats, feral dogs and cats, great blue herons, Mississippi kites, and owls has also been documented.[3][4][14]

References

- BirdLife International (2016). "Sternula antillarum". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T22694673A93462098. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22694673A93462098.en.

- Thompson, Bruce C.; Jackson, Jerome A.; Burger, Joanna; Hill, Laura A.; Kirsch, Eileen M.; Atwood, Jonathan L. (1997). Poole, A. (ed.). "Least Tern (Sterna antillarum)". The Birds of North America Online. Ithaca: Cornell Lab of Ornithology. doi:10.2173/bna.290.

- Draheim, H.; Baird, P.; Haig, S. (2012). "Temporal Analysis of mtDNA Variation Reveals Decreased Genetic Diversity in Least Terns". The Condor. 114 (1): 145–154. doi:10.1525/cond.2012.110007.

- Draheim, H.; Miller, M.; Baird, P.; Haig, S. (2010). "Subspecific Status and Population Genetic Structure of Least Terns (Sternula antillarum) Inferred by Mitochondrial DNA Control-Region Sequences and Microsatellite DNA". The Auk. 127 (4): 807–819. doi:10.1525/auk.2010.09222.

- Szcyzs, P.; Waddington, S.; Burr, T.; Baird, P. (2014). "Least Terns Nesting on the Big Island of Hawaii". Proceedings of the 38th Annual Meeting of the Waterbird Society. La Paz, Mexico.

- Marschalek, D. (2009). California Least Tern Breeding Survey 2009 Season (PDF) (Report). California Department of Fish and Game.

- Forys, Elizabeth A.; Borboen-Abrams, Monique (2006). "Roof-top Selection by Least Terns in Pinellas County, Florida". Waterbirds. The Waterbird Society. 29 (4): 501–506. doi:10.1675/1524-4695(2006)29[501:RSBLTI]2.0.CO;2.

- Tomkins, Ivan R. (1959). "Life history notes on the least tern" (PDF). Wilson Bulletin. 71 (4): 313–322.

- Baird, P. (2009). Foraging Study of California Least Terns in San Diego Bay and Near ocean Waters (Unpublished Report). San Diego California: U.S. Navy.

- Baird, P.; Hink, S.; Robinette, D.; Wawerchak, V. (1997). Monitoring of the Least Tern Colony during the X Games in Mission Bay Park, 1997 (Unpublished Report). ESPN and the City of San Diego.

- Baird, P.; Hink, S.; Robinette, D.; Wawerchak, V. (1998). Monitoring of the Least Tern Colony during the X Games in Mission Bay Park, 1998 (Unpublished Report). ESPN and the City of San Diego.

- Collins, L.; Bailey, S. (1980). California least tern nesting season at Alameda Naval Air Station - 1980 (Report).

- Zeiner, David C.; Laudenslayer, William F.; Meyer, Kenneth E., eds. (November 1988). California Wildlife. II, Birds. California Department of Fish and Game. ASIN B0026C80G6.

- Jones, Ken (1997–2006). "Least tern data archives".

- Field Guide to the Birds of North America. Washington, D.C.: National Geographic Society. 2002. ISBN 0-7922-6877-6.

- Farrand, John (1988). Audubon Handbook: Western Birds. McGraw Hill Book Company. ISBN 978-0-07-019977-4.

- Massey, B. (1974). "Breeding Biology of the California least tern". Proceedings of the Linnaean Society of New York. New York. 72: 1–24.

- Gary Deghi, C. Michael Hogan, et al., Biological Assessment for the Proposed Tijuana/San Diego Joint International Wastewater Treatment Plant, Publication of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Region IX, Earth Metrics Incorporated, Burlingame, CA with Harvey and Stanley, Alviso, CA

- Olsen, Klaus Malling; Larsson, Hans (1995). Terns of Europe and North America. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-04387-6.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sternula antillarum. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Sternula antillarum |

- Least tern Photo Field Guide on Flickr

- "Least tern media". Internet Bird Collection.

- Least tern photo gallery at VIREO (Drexel University)

- Interactive range map of Sternula antillarum at IUCN Red List maps

- Audio recordings of Least tern on Xeno-canto.

- Tern Colony: an individual-based model of Least Tern reproduction