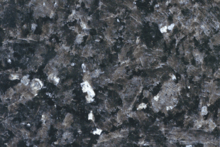

Larvikite

Larvikite is an igneous rock, specifically a variety of monzonite,[1] notable for the presence of thumbnail-sized crystals of feldspar. These feldspars are known as ternary because they contain significant components of all three endmember feldspars.[1] The feldspar has partly unmixed on the micro-scale to form a perthite, and the presence of the alternating alkali feldspar and plagioclase layers give its characteristic silver blue sheen (Schiller effect, labradorescence) on polished surfaces. Olivine can be present along with apatite, and locally quartz. Larvikite is usually rich in titanium, with titanaugite and/or titanomagnetite present.

_Larvik_Batholith_Norway.jpg)

Larvikite occurs in the Larvik Batholith (a.k.a. Larvik Plutonic Complex), a suite of 10 igneous plutons emplaced in the Oslo Rift (Oslo Graben) surrounded by ~1.1 billion year old Sveconorwegian gneisses. The Larvik Batholith is of Permian age, about 292–298 million years old.[2] Larvikite is also found in the Killala Lake Alkalic Rock Complex near Thunder Bay in Ontario, Canada.[3]

The name originates from the town of Larvik in Norway, where this type of igneous rock is found. Many quarries exploit larvikite in the vicinity of Larvik.

Formation

Intrusions of larvikite in Norway form part of the suite of igneous rocks that were emplaced during the Permian period, associated with the formation of the Oslo Rift. The crystallisation of a ternary feldspar indicates that this rock began to crystallise under lower crustal conditions.[1]

Uses

Larvikite is prized for its high polish and the labradorescence of its feldspar crystals, and is used as dimension stone, often cladding the facades of commercial buildings and corporate headquarters.[1] It is known informally as Blue Pearl Granite, although this is not an accurate description. Larvikite has been designated by the International Union of Geological Sciences as a Global Heritage Stone Resource.[4]

References

- Ramberg, I. B., Bryhni, I., Nottvedt, A. and Rangnes, K. (editors) (2008). The Making of a Land: Geology of Norway. Trondheim: Norsk Geologisk Forening (Norwegian Geological Association). p. 268. ISBN 978-82-92-39442-7.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Larvikite geology

- Sage, R.P. (1988). Geology of Carbonatite - Alkalic Rock Complexes in Ontario: Killala Lake Alkalic Rock Complex, District of Thunder Bay, Ontario Geological Survey Study 45 (PDF). Toronto: Ontario Geological Survey and the Ministry of Northern Development and Mines. pp. 9–18. ISBN 0-7729-0580-0.

- "Designation of GHSR". IUGS Subcommission: Heritage Stones. Retrieved 24 February 2019.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Larvikite. |

- Petrogenesis of the Oslo Region Larvikites and Associated Rocks (abstract) Journal of Petrology, 1980, volume 21, Number 3, pages 499-531

- Structure of the larvikite-lardalite complex, Oslo-region, Norway, and its evolution (abstract) International Journal of Earth Sciences, 1978, volume 67, number 1, pages 330-342