Larry Payne

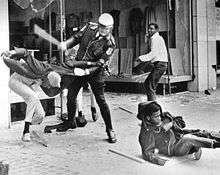

Larry Payne was a sixteen-year old African American teenager who was killed following a march in support of the Memphis Sanitation Strike on Thursday, March 28, 1968, in Memphis, Tennessee.[1] He was the only fatality on that day although the New Pittsburgh Courier reported 60 injured and 276 arrested.[2]

Martin Luther King Jr. called Payne's mother, Lizzie Payne, on the phone to console her after her son's brutal death at the hands of Patrolman Leslie Dean Jones.[3]

Events leading up to Payne's death

Conflicting accounts describe the looting that occurred in tandem with the march on Thursday March 28 1968 that led to a city-wide curfew and Mayor Loeb calling the Tennessese National Guard.

Payne's funeral

There was a five-hour wake the day before the funeral on Monday, April 1, 1968.[4] Six hundred attended his funeral at Clayborn Temple on Tuesday, April 2, 1968.[5] Striking sanitation workers, clergy members who supported the strike, and national television representatives were all in attendance as well as the students and faculty of Mitchell Road High School where Payne was enrolled prior to his death. Rev. B.T. Dumas, pastor of New Philadelphia Baptist Church gave the eulogy entitled "Man Is Like Grass And Is Cut Down in Various Stages of Life." Surprisingly, Rev. Dumas made no reference to the unusual circumstances of Payne's death.[5] Payne's mother, Lizzie Mason Payne, had to be led from the church she was so full of grief. The Washington Post quoted her as saying: "They killed you like a dog."[6]

Events after Payne's death

King planned to visit Payne's mother during his next visit to Memphis, but was killed before the visit could occur.[1] He was assassinated seven days later, on April 4, 1968, when he returned to Memphis in an effort to hold a peaceful march unmarred by looting and violence.

After Payne's death, Lizzie Payne, his mother, moved to Flint, Michigan.[3]

References

- "Larry Payne". Civil Rights and Restorative Justice. Northwestern University School of Law. Archived from the original on February 27, 2018. Retrieved 23 October 2015.

- Ratcliff, Robert M. (April 6, 1968). "Memphis: King's Biggest Gamble--March Was Out of Hand Before It Even Started". New Pittsburgh Courier.

- "83 year old mother grieves son's death". Commercial Appeal via Democratic Underground. Gannett. Retrieved 23 October 2015.

- Special to the Daily Defender (April 1, 1968). "Probe Killing of Memphis Youth". Chicago Defender (Daily Edition).

- Reid, McCann (April 2, 1968). "600 Attend Funeral for Young Riot Victim". Chicago Defender (Daily Edition).

- "Memphis Riot Victim Buried". The Washington Post(Times Herald). April 3, 1968.

External links

- "My thoughts: Wither Larry Payne, civil rights and hallowed grounds?" Commercial Appeal, February 27, 2016.

- Interview with Larry Payne's mother, brother, and sister (Recorded: March 2, 2010)

- FBI to Re-Open Memphis Civil Rights era cold case (WMC Channel 5 News)

- For Larry Payne (a poem commissioned by Fusion Theatre Company and written by Hakim Bellamy, November 9, 2013)