Clayborn Temple

Clayborn Temple, formerly Second Presbyterian Church, is a historic place in Memphis, Tennessee, United States. It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1979 for local architectural significance. It was upgraded to national significance under Clayborn Temple in 2017 due to its role in the events of the Sanitation Workers' Strike of 1968. The historic structure was sold to the A.M.E. Church in 1949, which named the building after their bishop.[2]

Clayborn Temple | |

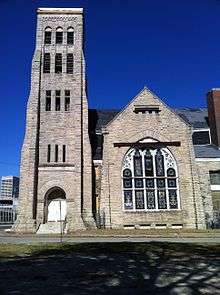

The church from the Historic American Buildings Survey | |

| |

| Location | 294 Hernando St, Memphis, Tennessee |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 35°8′7″N 90°3′4″W |

| Area | 0.6 acres (0.24 ha) |

| Built | 1891 |

| Architect | Kees & Long; E.C. Jones |

| Architectural style | Romanesque |

| NRHP reference No. | 79002478[1] |

| Added to NRHP | September 4, 1979 |

History

In 1888, the congregation of Second Presbyterian Church decided to purchase a lot on the corner of Pontotoc and Hernando for the construction of its new building. Ground was broken for the construction on February 2, 1891, and the cornerstone of the church was laid on May 14.[3] Sunday, January 1, 1893, the church had its dedication service. All the presbyterian pastors of the city joined the congregation for the service.[3]

The congregation moved to East Memphis and sold the building to the African Methodist Episcopal Church in 1949. Throughout the 1960s, Clayborn Temple became the city's staging ground for the civil rights movement, particularly the organizing headquarters of the Memphis Sanitation Strike.

Architecture

Built in 1891, this Romanesque Revival ecclesiastical architecture has cross gabled roofs, constructed of limestone blocks, rusticated externally with heavy timber framing members forming the roof trusses, nave ceiling with wood beams that are suspended from the roof trusses by 2 x 4 studs. It has several unique features, for instance the chancel is situated in the corner rather that the center of the sanctuary. When Second Presbyterian dedicated its new sanctuary on January 1, 1892, it was the largest church in America south of the Ohio River.[3]

Civil Rights Movement

Throughout the 1960s, Clayborn Temple became the city's staging ground for the civil rights movement.[4] In Memphis, the link between racial and economic injustices in the city became increasingly apparent. Memphis Labor Unions had tried for years to reform Memphis Public Works policies that included discrimination, unfair working conditions, and drastically insufficient wages. The deaths of two city sanitation workers, Echol Cole and Robert Walker on February 1, 1968, united the Sanitation Workers, labor unions, religious communities, and the black middle class to work together and create a grassroots movement in Memphis.

On February 12, 1968, 1,300 Sanitation Workers went on strike from Memphis City Department of Public Works, led by T.O. Jones, a union organizer for AFSCME Local 1733, and Jerry Wurf, the national president of AFSCME. From this day forward, the strikers marched 1.3 miles each day from Clayborn Temple to City Hall.[4] As they marched, other local organizations began to partner with them, preventing the Sanitations Workers’ families from ever going hungry. These organizations included the Mallory Knights, the Invaders, and Community On the Move for Equality (C.O.M.E.), which was a group of 150 local ministers led by Reverend James Lawson.[5] In the middle of this struggle for justice were Clayborn Temple's ministers. Rev. Ralph Jackson, the director of the A.M.E. Minimum Salary building next door to Clayborn, gave impassioned speeches to the supporters of the strike at Clayborn. The most consistent white supporter of the movement was Clayborn's pastor, Rev. Malcolm Blackburn.[4] He opened Clayborn's offices, classrooms, and sanctuary to host the strategy meetings and community gatherings throughout the strike.[5] In March 1968, after weeks of marching to City Hall from Clayborn Temple, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., came to Memphis in support of the sanitation workers’ efforts. He had been invited by Reverend Lawson and C.O.M.E. to shine a national spotlight on their efforts in the fight for economic justice. Dr. King and organizers of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) helped to plan a strategic march with Dr. King leading the way.

On Thursday, March 28, marchers began gathering at Clayborn Temple in anticipation of Dr. King. Nearly 15,000 marchers participated. Students from Memphis schools left the classroom to join the march. He arrived around 11:05 am, and they began the march with King and the sanitation workers, who had been marching this same path for weeks, in the front, while youths ran about throughout the march, pressing to get to the front.[5]

After marching only half a mile, the youth's agitation, derived from a rumor that the police had killed a Hamilton High Student earlier that morning, erupted into vandalism, looting, and rioting. The police reacted brutally to the riot, launching against both nonviolent protesters and the youth. Reverend Lawson and Reverend Jackson urged protesters to return to Clayborn Temple. The marchers retreated to Clayborn Temple, while police surrounded the building. “The interior of Clayborn looked like the aftermath of a war,” Kathy Pittman Black reported.[5] The entire building was filled with many injured and terrified protesters. The police attacked those that tried to the leave the church with mace, tear gas, and clubs.[5] At one point, police even entered the church, swinging clubs and shooting tear-gas canisters.

The day ended as 4,000 heavily armed National Guardsmen troops poured into the city.[5] Two hundred eighty people had been arrested during the riot, and 60 were reported injured. One sixteen-year-old boy, Larry Payne died at the hands of a police officer that day, shot in the stomach after being suspected of looting.[4] Payne's funeral was held in Clayborn Temple on April 2, 1968, and Rev. Harold Middlebrook said, "We really felt his death was related to the movement."[4] Despite police pressure to have a private closed-casket funeral in their home, the family held the funeral at Clayborn and had an open casket.

Dr. King was rushed back to his hotel when the strike erupted into a riot on March 28, 1968. He vowed he would return to Memphis to lead a successfully peaceful march. King returned to Memphis a week later, but was assassinated on April 4, 1968 before his second march from Clayborn took place. On April 16, a deal was finally negotiated for union recognition and better wages for the sanitation workers.[5] The strike had come to an official end.

After King's assassination, Clayborn Temple remained a key refuge and meeting place for the Memphis Civil Rights Movement. The church was used extensively during the 1969 Black Monday protests, led by Ezekiel Bell and the NAACP. Black Mondays were designed to secure African American representation on the school board and further desegregate the public schools. In November 1969, mass meetings were held at Clayborn Temple while thousands of protesters led by Dr. King's successor, Reverend Ralph Abernathy, marched from the church which remained the epicenter of the Black Monday demonstrations until late November when a compromise was reached, with two African Americans appointed to the school board.

Disrepair and Restoration

As Clayborn's congregation began to grow smaller and smaller, the upkeep of the magnificent building was hard to manage. Eventually, though, the congregation moved from Clayborn, and it was left vacant by the AME for over a decade.

Having been vacant for a number of years, a group of Memphians began the process of rehabilitating the church in October 2015.[6]

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Clayborn Temple (Memphis, Tennessee). |

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. March 13, 2009.

- Church, Barbara Hume; Dalton, Robert E. (July 12, 1979). "Second Presbyterian Church, Memphis, Tennessee". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- Gillespie, Charles C. (1971). A History of The Second Presbyterian Church of Memphis, Tennessee. Memphis, Tennessee: Second Presbyterian Press. pp. 31–63.

- Beifuss, Joan Turner (1985). At The River I Stand. Memphis: B & W Books. pp. 116–117, 240–242, 263. ISBN 0-9614996-0-5.

- Honey, Michael K. (2007). Going Down Jericho Road. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-04339-6.

- "Clayborn Temple in Downtown Memphis is being revitalized - Memphis Business Journal". Memphis Business Journal. Retrieved 2016-10-21.