Larcum Kendall

Larcum Kendall (21 September 1719 in Charlbury, Oxfordshire – 22 November 1790 in London) was a British watchmaker.

Larcum Kendall | |

|---|---|

| Born | 21 September 1719 |

| Died | 22 November 1790 (aged 71) |

| Occupation | Watchmaker |

Early life

Kendall was born on 21 September 1719 in Charlbury. His father was a mercer and linen draper named Moses Kendall, and his mother was Ann Larcum from Chepping Wycombe in Buckinghamshire; they married on 18 June 1718. The family were Quakers. The cottage where they lived is thought to be on the site of Charlbury's post office on Market Street. He had a brother, Moses.[1]

In 1735 Kendall was apprenticed to the London watchmaker John Jeffreys. He was living with his parents in St Clement Danes at the time.[1] Jeffreys created a pocket watch for John Harrison, who later used ideas from pocket watches in his H4 chronometer.[2]

Kendall set up his own business in 1742, working with Thomas Mudge to make watches, working for the watch and clock maker George Graham. In 1765 he was one of six experts selected by the Board of Longitude to witness the operation of John Harrison's H4, which he was subsequently asked to duplicate.[1]

K1

The first model finished by Kendall was an accurate copy of John Harrison's H4, cost £450, and is known today as K1.[3] It was engraved in 1769, and was presented to the Board of Longitude on 13 January 1770,[2][4] at which point he was given a bonus of £50.[3] The original H4, the first successful chronometer, had an astronomical price of £400 in 1750, which was approximately 30% of the value of a ship.

James Cook and astronomer William Wales tested the clock on Cook's second South Seas journey aboard HMS Resolution, 1772–75[5] and were full of praise after initial scepticism. "Kendall's watch has exceeded the expectations of its most zealous advocate," Cook reported in 1775 to the admiralty.[6] Cook also described it in his log as "our trusty friend the Watch" and "our never-failing guide the Watch".[2] It was thus K1 which proved to a doubting scientific establishment that H4's success was no fluke. Three other clocks, constructed by John Arnold, had not withstood the loads of the same journey. Although constructed like a watch, the chronometer had a diameter of 13 centimetres (5.1 in) and weighed 1.45 kilograms (3.20 lb).

K1 was used again by Cook for his third voyage (HMS Resolution 1776–80). In April 1779 off Kamchatka K1 stopped. A seaman with watchmaking experience cleaned it and started it again, but in June the balance spring broke and it could not be repaired. After its arrival in Britain in September 1780 it was returned to Kendall for repairs. K1 left England in May 1787 with the First Fleet voyaging to New South Wales in HMS Sirius.[7] K1 was transferred to HMAT Supply in the Indian Ocean, and arrived at Botany Bay on 18 January 1788. After some months ashore with Astronomer Lieutenant William Dawes, K1 was returned to HMS Sirius and travelled to Cape Town to collect supplies for the colony. After the wreck of Sirius at Norfolk Island in March 1790, K1 was put on board HMAT Supply which went to Batavia to collect more supplies, and eventually took K1 back to England via Cape Horn arriving in Plymouth in April 1792.

K1 went to sea with Admiral Sir John Jervis in 1793. He took it to the West Indies and the Mediterranean and it was on board HMS Victory at the Battle of Cape St Vincent. It was finally "pensioned off" to Greenwich in 1802. K1 was described by John Gilbert, Master of the Resolution on Cook's second voyage as "The greatest piece of mechanism the world has ever seen".

K1 is now kept in the Royal Observatory, Greenwich at the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, England. In 1988 K1 went to Sydney for Australia's Bicentenary and spent some months in Sydney's Powerhouse Museum. In 2007 K1 went to the United States for the "Maps" exhibition in Chicago.

K2

Kendall was asked in 1770 to instruct other workmen on how to manufacture parts for additional replicas of H4; however, he declined stating that further replicas would "still come to so high a price; as to put it far out of the reach of purchase for general use". He assured the Board that he would be able to modify Harrison's design to build a similar but simpler watch for around £200, half the price of K1.[3] He received the order and K2 was manufactured in 1771 (the date inscribed on the watch), and completed in 1772.[8] It was given in 1773 to Constantine Phipps for its expedition for the search of a Northwest Passage, then it was assigned in North America. It worked less exactly than the original. William Bligh in his 1787 log of HMS Bounty, recorded a daily inaccuracy of between 1.1 and three seconds and that it had varied irregularly.

The chronometer attained fame because of the mutiny on the Bounty. The timekeeper was taken by the mutineers following the loss of the Bounty, a fact for which Bligh subsequently apologised to Sir Harry Parker.[9] It returned to England many years later after an odyssey. The American ship's captain Mayhew Folger rediscovered Pitcairn Island in 1808 and was given the chronometer by the one remaining mutineer there, John Adams. The Spanish governor of Juan Fernandez Island confiscated the watch. The chronometer was later purchased for three doubloons by a Spaniard named Castillo. When he died, his family conveyed it to Captain Herbert of HMS Calliope, which sailed from Valparaiso on 1 July 1840, who gave it to the British Museum around 1840.[10]

It is now held by the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich, England having previously being held by the Royal United Service Institution's Museum and transferred to National Maritime Museum in the 1960s. K2 went to Sydney to be part of the Bligh and Mutiny on the Bounty exhibition at the Mitchell Library in 1991.

K3

Kendall simplified his design further, and his third and final watch K3 cost £100 in 1774,[3] but did not have the required accuracy. James Cook used K3 on his third voyage on board HMS Discovery in 1776–79.[1] It was also used again by George Vancouver (in a later HMS Discovery) from 1791 to 1795 during which time he charted the southwest coast of Australia and did detailed surveys of the coast of North America.

During Matthew Flinders' journey to Australia in 1801, astronomer John Crossley became sick and left HMS Investigator in Cape Town. K3 was given to replacement astronomer James Inman in late 1802 to take to Australia for Flinders. Flinders mainly used the two new Earnshaw's #520 and #546. His other chronometers, Arnold's older #82 and #176, both stopped early in the voyage. K3 was only used by Flinders to chart Wreck Reef. It was taken back to England by Inman.

All three of Kendall's chronometers had been to Australia by August 1788, one of them twice.

K3 is also now kept at the Royal Observatory, Greenwich. In 1978 K3 was taken to Canada to be part of "Discovery 1778", an exhibition at the Vancouver Centennial Museum. In the 1988 K3 went to Australia for Brisbane's Expo and an exhibition at the Mitchell Library in Sydney.

Later life and death

Kendall was a first-class craftsman but not a technical designer. After K3 Kendall built chronometers to the design of John Arnold.

His home was Furnival's Inn Court, London, where he died on 22 November 1790.[11] He was buried on 28 November in the Quaker burial ground in Kingston. His brother, Moses, had his personal effects and the contents of his workshop auctioned by Christie's.[1]

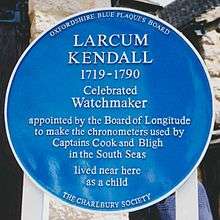

A blue plaque about Kendall was unveiled on 3 May 2014 in the garden of Charlbury Museum, and erected on the wall of the Post Office,[12] close to his childhood home (since the house no longer stands).[13]

Further reading

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Larcum Kendall. |

- Baillie, G. H. (2008). Watchmakers & Clockmakers of the World. ISBN 978-1443733533.

- Poland, Peter (February 1991). The Travels of the Timekeepers. Sydney, Australia. ISBN 0958794839.

References

- "Oxfordshire Blue Plaques Scheme: plaque to Larcum Kendall in Charlbury, with biography". Retrieved 15 April 2015.

- Andrewes, William J. H. (November 1996). The Quest for Longitude: The Proceedings of the Longitude Symposium Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts November 4–6, 1993. pp. 226, 252. ISBN 978-0964432901.

- Dunn, Richard; Higgitt, Rebekah (2014). Ships, Clocks & Stars: The Quest for Longitude. Collins. ISBN 978-0007940523.

- "Confirmed Minutes of the Board of Longitude, 1737–1779". Cambridge Digital Library. Retrieved 15 April 2015.

- Wales, William. "Log book of HMS 'Resolution'". Cambridge Digital Library. Retrieved 28 May 2013.

- Beaglehole, J. C. (1974). The Life of Captain James Cook. Stanford University Press. p. 438. ISBN 0804720096.

- Correspondence, Daniel Southwell, Midshipman HMS Sirius, 12 July 1788. Cited in Bladen, F. M., ed. (1978). Historical records of New South Wales. Vol. 2. Grose and Paterson, 1793–1795. Lansdown Slattery & Co. p. 685. ISBN 0868330035.

- "K2". National Maritime Museum. Retrieved 15 April 2015.

- Bligh, William. "Letter from Captain William Bligh to Sir Harry Parker". Cambridge Digital Library. Cambridge University Library. Retrieved 15 April 2015.

- "Mayhew Folger's account of meeting the Bounty descendants". Retrieved 15 April 2015.

- "Obituary of Larcum Kendall". The Gentleman's Magazine. 1790.

- "Honouring Charlbury's Favourite Son". Retrieved 29 January 2017.

- "Honour for maritime history maker". Oxford Mail. 24 April 2014. Retrieved 15 April 2015.