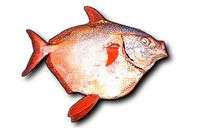

Opah

Opahs (also commonly known as moonfish, sunfish (not to be confused with Molidae), kingfish, redfin ocean pan, and Jerusalem haddock) are large, colorful, deep-bodied pelagic lampriform fishes comprising the small family Lampridae (also spelled Lamprididae). In 2015 the Opah was discovered to have near whole body endothermy, a form of regional endothermy.[2][3][4] This is different from "warm blooded" in the sense of birds and mammals and is not the first fish discovered with this ability.[5] It may be the most completely endothermic fish.[2] Other species of fish also possess this ability, such as tuna and some sharks.[5] Only two living species occur in a single genus: Lampris (from the Greek lamprid-, "brilliant" or "clear"). One species is found in tropical to temperate waters of most oceans, while the other is limited to a circumglobal distribution in the Southern Ocean, with the 34th parallel south as its northern limit. Two additional species, one in the genus Lampris and the other in the monotypic Megalampris,[6] are only known from fossil remains. The extinct family, Turkmenidae, from the Paleogene of Central Asia, is closely related, though much smaller.

| Opah | |

|---|---|

| |

| Lampris guttatus | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | Lampridae |

| Genus: | Lampris Retzius, 1799 |

| Species | |

|

See text | |

Description

Opahs are deeply keeled, compressed, discoid fish with conspicuous coloration: the body is a deep red-orange grading to rosy on the belly, with white spots covering the flanks. Both the median and paired fins are a bright vermilion. The large eyes stand out, as well, ringed with golden yellow. The body is covered in minute cycloid scales and its silvery, iridescent guanine coating is easily abraded.

Opahs closely resemble in shape the unrelated butterfish (family Stromateidae). Both have falcated (curved) pectoral fins and forked, emarginated(notched) caudal fins. Aside from being significantly larger than butterfish, opahs have enlarged, falcated pelvic fins with about 14 to 17 rays, which distinguish them from superficially similar carangids—positioned thoracically; adult butterfish lack pelvic fins. The pectorals of opahs are also inserted (more or less) horizontally rather than vertically. The anterior portion of an opah's single dorsal fin (with about 50–55 rays) is greatly elongated, also in a falcated profile similar to the pelvic fins. The anal fin (around 34 to 41 rays) is about as high and as long as the shorter portion of the dorsal fin, and both fins have corresponding grooves into which they can be depressed.

The snout is pointed and the mouth small, toothless, and terminal. The lateral line forms a high arch over the pectoral fins before sweeping down to the caudal peduncle. The larger species, Lampris guttatus, may reach a total length of 2 m (6.6 ft) and a weight of 270 kg (600 lb). The lesser-known Lampris immaculatus reaches a recorded total length of just 1.1 m (3.6 ft).

Regional endothermy

The Opah is the newest addition to the list of regionally endothermic fish (warm-blooded), with a rete mirabile in its gill tissue structure.[5] Other fish like the tunas, billfish and Lamnid sharks also possess this ability.[5] This was first described in the Opah in 2015 as exhibiting counter-current heat exchange in which the arteries, carrying warm blood, from the heart, warm the veins in the gills carrying cold blood.[2][4] The gills are cooled by contact with cold water. The opah's pectoral muscles generate most of its body heat.[2] The opah retains heat with insulating layers of fat, which insulates the heart from the gills, and the pectoral muscles from the surrounding water.[2] The opah is not homeothermic (maintaining a stable internal temperature) like birds and mammals. Fish like the Opah maintain an internal temperature higher than the surrounding water but not a constant temperature the way that mammals do.[2] Mammals are able to maintain a constant temperature, in humans it's around 37 °C.[7] Humans maintain this temperature regardless of the temperature outside the body via various physiological methods. Fish like the Opah do not do this, they maintain a temperature higher than the water temperature around them but it is still regulated by the water temperature. Most species of fish cannot do this. This ability is what makes the Opah, and other species of fish like Bluefin Tuna, special.

Behavior

Almost nothing is known of opah biology and ecology. They are presumed to live out their entire lives in the open ocean, at mesopelagic depths of 50 to 500 m, with possible forays into the bathypelagic zone. They are apparently solitary, but are known to school with tuna and other scombrids. The fish propel themselves by a lift-based labriform mode of swimming, that is, by flapping their pectoral fins. This, together with their forked caudal fins and depressible median fins, indicates they swim at constantly high speeds like tuna.

Lampris guttatus are able to maintain their eyes and brain at 2 °C warmer than their bodies, a phenomenon called cranial endothermy and one they share with sharks in the family Lamnidae, billfishes and some tunas.[8][5] This may allow their eyes and brains to continue functioning during deep dives into water below 4 °C.[8]

Squid and euphausiids (krill) make up the bulk of the opah diet; small fish are also taken. Pop-up archival transmitting tagging operations have indicated, aside from humans, large pelagic sharks, such as great white sharks and mako sharks, are primary predators of opah. The tetraphyllidean tapeworm Pelichnibothrium speciosum has been found in L. guttatus, which may be an intermediate or paratenic host.[9] The planktonic opah larvae initially resemble those of certain ribbonfishes (Trachipteridae), but are distinguished by the former's lack of dorsal and pelvic fin ornamentation. The slender hatchlings later undergo a marked and rapid transformation from a slender to deep-bodied form; this transformation is complete by 10.6 mm standard length in L. guttatus. Opahs are believed to have a low population resilience.

Species and range

Two living species are traditionally recognized, but a taxonomic review in 2018 found that more should be recognized (the result of splitting L. guttatus into several species, each with a more restricted geographic range), bringing the total to six.[10] The six species of Lampris have mostly non-overlapping geographical ranges, and can be recognized based on body shape and coloration pattern.[10]

- Lampris australensis Underkoffler, Luers, Hyde & Craig, 2018 Southern spotted opah — Southern hemisphere, in the Pacific and Indian oceans.[10]

- Lampris guttatus (Brünnich, 1788) North Atlantic opah — formerly thought to be cosmopolitan, but now thought to be restricted to the North-Eastern Atlantic including the Mediterranean Sea.[10]

- Lampris immaculatus Gilchrist, 1904 southern opah — confined to the Southern Ocean from 34°S to the Antarctic Polar Front

- Lampris incognitus Underkoffler, Luers, Hyde & Craig, 2018 smalleye Pacific opah — central and eastern North Pacific Ocean.[10]

- Lampris lauta Lowe, 1860 East Atlantic opah — Eastern Atlantic Ocean, including the Mediterranean, Azores and Canary Islands.[10]

- Lampris megalopsis Underkoffler, Luers, Hyde & Craig, 2018 bigeye Pacific opah — cosmopolitan, including the Gulf of Mexico, Indian Ocean, the Western Pacific Ocean and Chile.[10]

Known fossil taxa

- Lampris zatima, also known as "Diatomœca zatima", is a very small, extinct species from the late Miocene of what is now Southern California known primarily from fragments, and the occasional headless specimens.[11]

- Megalampris keyesi is an extinct species estimated to be about 4 m in length. Fossil remains date back to the Late Oligocene of what is now New Zealand, and it is the first fossil lampridiform found in the Southern Hemisphere.[6]

References

- Sepkoski, Jack (2002). "A compendium of fossil marine animal genera". Bulletins of American Paleontology. 364: 560. Archived from the original on 20 February 2009. Retrieved 8 January 2008.

- Wegner, Nicholas C., Snodgrass, Owen E., Dewar, Heidi, John, Hyde R. Science. "Whole-body endothermy in a mesopelagic fish, the opah, Lampris guttatus". pp. 786–789. Retrieved May 14, 2015.

- Pappas, Stephanie; LiveScience. "First Warm-Blooded Fish Discovered". Scientific American. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- "Warm Blood Makes Opah an Agile Predator". Fisheries Resources Division of the Southwest Fisheries Science Center of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. May 12, 2015. Retrieved May 15, 2015. "New research by NOAA Fisheries has revealed the opah, or moonfish, as the first fully warm-blooded fish that circulates heated blood throughout its body..."

- Moyle, Peter B. (2004). Fishes : an introduction to ichthyology. Cech, Joseph J. (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-100847-1. OCLC 52386194.

- Gottfried, Michael D., Fordyce, R. Ewan, Rust, Seabourne. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. "Megalampris keyesi, A Giant Moonfish (Teleostei, Lampridiformes), from the Late Oligocene of New Zealand". pp. 544–551.

- "Human body temperature", Wikipedia, 12 January 2020, retrieved 13 January 2020

- Bray, Dianne. "Opah, Lampris guttatus". Fishes of Australia. Retrieved 16 September 2014.

- Scholz et al., 1998.

- Karen E. Underkoffler; Meagan A. Luers; John R. Hyde; Matthew T. Craig (2018). "A Taxonomic Review of Lampris guttatus (Brünnich 1788) (Lampridiformes; Lampridae) with Descriptions of Three New Species". Zootaxa. 4413 (3): 551–565. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.4413.3.9. PMID 29690102.

- David, Lore Rose. 10 January 1943. Miocene Fishes of Southern California The Society