La Veneno

Cristina Ortiz Rodríguez (19 March 1964 – 9 November 2016), better known as La Veneno ("Poison"), was a Spanish singer, actress, sex worker and media personality. She rose to fame on the late-night talk shows Esta noche cruzamos el Mississippi and La sonrisa del pelícano, broadcast in Spain between 1996 and 1997 and hosted by the journalist Pepe Navarro.

La Veneno | |

|---|---|

.png) Ortiz in October 2016 | |

| Born | 19 March 1964 Adra, Almería |

| Died | 9 November 2016 (aged 52) Madrid, Spain |

| Cause of death | Traumatic brain injury after accidental fall |

| Other names | Cristina Ortiz Rodríguez |

| Occupation |

|

| Years active | 1996–2016 |

La Veneno was one of the first transgender women to become widely known in Spain, and has since been recognised as a pioneering trans icon.[1] In 2020, a critically acclaimed series following her life became a hit show in Spain.

Early life

La Veneno was born in Adra, Almería,[2] the daughter of José María Ortiz López and María Jesús Rodríguez Rivera.[3][4] She noted from an early age that she was different from other children, and in her adolescence she realised that she was in fact transgender. She suffered aggression and abuse from people in her hometown who did not accept her gender identity.

Career

In 1991 she left her hometown for Madrid. Later, in 1992, she started her process of transition and she worked as a prostitute in the Parque del Oeste in Madrid. There she was discovered in 1996 by the reporter Faela Saiz, who interviewed her for a TV feature on prostitution for the late-night show Esta noche cruzamos el Mississippi on Telecinco[5]. The interview, showcasing La Veneno's outrageous humour, was a hit. The show's host, Pepe Navarro, subsequently invited her to become a regular contributor. Her rise to fame was almost immediate, and she helped the programme reach viewing figures of almost eight million. Later, she contributed to the programme La sonrisa del pelícano (1997) on Antena 3. [6]

La Veneno recorded two singles, Veneno pa' tu piel and El rap de La Veneno, and her career as a vedette and show-woman took off. She toured Spain, performing in galas and making personal appearances at nightclubs and festivals. When La sonrisa del pelícano ended, she spent a month doing TV work in Buenos Aires, before returning to Spain and participating in other programmes for Telemadrid and Antena 3, among other channels. She also took part in two pornographic films, El secreto de la Veneno and La venganza de la Veneno. She also acted in six episodes of the series En plena forma, starring Alfredo Landa.

Prison term

In 2003, Cristina was implicated in a case of arson and insurance fraud, and she was reported to the police by her then-boyfriend Andrea Petruzzelli. She was accused of intentionally setting fire to her flat in order to claim the insurance money. She was found guilty, and sentenced to three years in prison.[7] She was sent to an all-male prison.

Media coverage

Upon leaving prison, in 2006, Cristina told the media that she had been raped and abused by the prison guards. [8] This was disputed by the Spanish prison authorities. She spoke openly about her weight gain in prison, and she was invited onto several television programmes, her career apparently recovering. In October 2010, the sensationalist Spanish TV show ¿Dónde estás corazón? challenged La Veneno to lose all the weight she had put on. By March 2011, La Veneno had lost 35 kg. It was subsequently revealed that she had been suffering from bulimia and severe depression, as well as suffering deep anxiety.

On 10th May 2013, La Veneno appeared on Sálvame Deluxe on Telecinco to promote her book Ni puta, ni santa (Las memorias de La Veneno) ('Not a Whore, Not a Saint (The Memories of La Veneno)'). In August 2013, she revealed that her ex-boyfriend had fled with all her savings, over 60,000 euros, and she was living on just 300€ a month in benefits.[9]

In 2014 she was sent back to prison, this time a female prison, for eight months. On 3 October 2016, she finally launched her long-awaited memoir, Digo! Ni puta ni Santa. Las memorias de La Veneno, co-written with the help of her friend, the journalist and writer Valeria Vegas.[10]

Death

On 5 November 2016, Cristina had been found semi-conscious in her house, covered with bruises and with a deep wound to the head, which caused a traumatic brain injury.[11] [12] She was found there by her boyfriend, and there were bloodstains in her bathroom. She was taken by ambulance to the Hospital Universitario La Paz, where she was placed in an induced coma as a preventative measure. She remained in intensive care. Cristina died four days later, on 9 November 2016.[13] The post mortem determined that the cause of death was an accidental fall.[14] She had apparently taken a very large dose of Trankimazin tablets and alcohol. A second post mortem reached the same verdict.

While she was hospitalised in the ICU,[15] people close to La Veneno speculated that the death was not accidental,[16] because she received death threats after the publication of her autobiography,[17] which talked about affairs she had with powerful people.[18]

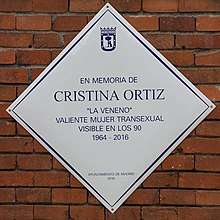

Her ashes were scattered half in the Parque del Oeste, and half in her hometown of Adra. In 2017, a plaque was unveiled to honour her in the Parque del Oeste. [19]

The 2020 TV series Veneno is based on her life.[20]

References

- León, Pablo (14 April 2019). "La Veneno: prostituta, icono trans y una muerte sospechosa". El País (in Spanish). ISSN 1134-6582. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- León, José Antonio (11 November 2016). "Los vecinos de Adra hablan de la infancia de La Veneno, Joselito, como era allí conocida". Telecinco (in Spanish). Mediaset España. Retrieved 4 August 2018.

- "Así fue la vida de Cristina La Veneno, antes conocida como Joselito". Telecinco. Mediaset España. 10 November 2016. Retrieved 4 August 2018.

- "Familiar de La Veneno: "Su madre ha sido siempre muy frívola y homófoba..."". Telecinco. Mediaset España. 11 November 2016. Retrieved 4 August 2018.

- H/Creada:04-04-2020, Ángeles LópezÚltima actualización:05-04-2020 | 20:39 (4 April 2020). "Cristina Ortiz, "La Veneno": Así se descubrió a la artista". La Razón (in Spanish). Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- Fernández, Ángel (11 June 2007). "Ningún espacio seduce masivamente a la gran audiencia trasnochadora". El Mundo (in Spanish). Madrid: Mundinteractivos, SA. Archived from the original on 27 December 2007. Retrieved 4 August 2018.

- "Cristina Ortiz, «La Veneno»: de la gloria televisiva a las violaciones en la cárcel". abc (in Spanish). 31 May 2019. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- QMD!, Por (15 November 2016). "Así fue la infernal vida de La Veneno". Que Me Dices (in Spanish). Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- Diéguez, Antonio (12 November 2016). "La Veneno, perdida por los hombres de mal vivir". El Mundo (in Spanish). Unidad Editorial. Retrieved 12 November 2016.

- J. B. L. (10 October 2016). "'La Veneno' desvela en sus memorias sus relaciones con políticos y futbolistas". Libertad Digital (in Spanish). Retrieved 4 August 2018.

- ""La Veneno", en coma tras ser hallada con un golpe en la cabeza y numerosas contusiones". Diario ABC (in Spanish). Madrid. 7 November 2016. Retrieved 12 November 2016.

Creen que las declaraciones de la actriz, donde afirmó que había estado con hombres muy poderosos del país pudo provocar algún tipo de venganza. Al parecer, había recibido varias amenazas acerca de unas informaciones que tenía pensado dar en exclusiva en su próxima aparición televisiva.

- Barroso, Francisco Javier (7 November 2016). "La Veneno, ingresada en coma en el hospital La Paz". El País (in Spanish). Madrid: Prisa. Retrieved 4 August 2018.

- F. Durán, Luis (9 November 2016). "Muere La Veneno". El Mundo (in Spanish). Unidad Editorial. Retrieved 12 November 2016.

- Bayón, Ángel (13 November 2016). "La autopsia confirma que La Veneno murió por una caída accidental". La Razón (in Spanish). Retrieved 27 March 2018.

- "Muere 'La Veneno', tras estar 4 días en coma". Lecturas (in Spanish). 9 November 2016. Retrieved 11 November 2016.

- Higuera, Raoul (7 November 2016). "La Veneno, en coma tras recibir una paliza por un "ajuste de cuentas"". El Confidencial (in Spanish). Titania Compañía Editorial, SL. Retrieved 11 November 2016.

- Guerra, Andrés (10 October 2016). "La Veneno: "Me he acostado con gente que con un dedo mueve España"". La Vanguardia (in Spanish). Retrieved 11 November 2016.

- Bryant, Tony (9 November 2018). "Suspicious death of transsexual vedette artiste". SURinEnglish.com. Retrieved 19 March 2020.

- QMD!, Por (13 November 2017). "Cristina 'La Veneno' ya tiene una placa conmemorativa "provisional" en Madrid". Que Me Dices (in Spanish). Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- Beatriz Martínez (29 March 2020). "'Veneno': ¿Quién es quién en la nueva serie de Javier Calvo y Javier Ambrossi?". Retrieved 1 April 2020.