La Saline, Missouri

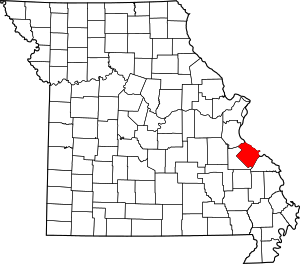

La Saline is an abandoned village located in Beauvais Township in Sainte Genevieve County, Missouri, United States. La Saline was located approximately six miles south of Sainte Genevieve.[1]

Etymology

La Saline is French and refers to the two natural salt springs found in the area, which also gave name to the nearby creek and its tributaries called Saline Creek or Saline River. The French colonials knew Saline Creek as La Rivière de la Saline or La Petite Rivière de la Saline. The Spanish referred to the creek and its tributaries as Las Salinas. There were two settlements, La Grande Saline and La Petite Saline, with the former being the larger of the two. La Grande Saline was usually simply referred to as La Saline, and sometimes as Old Saline.[2][3]

History

In 1541, Spanish explorer De Soto had sent Hernando de Silvera and Pedro Moreno from Capaha, with Indian guides, to obtain a supply of salt from a saline stream to the north, presumably the Saline Creek in Ste. Genevieve County.[4][5]

Later, during the French colonial period, both French and Illinois Indians came to the site of La Saline to get their salt.

The settlement of the Saline River began in the early 1700s. In 1715, a small party of French were reported to be making salt at La Saline. The early encampment at La Saline was temporary, but over time became permanent.[6] Two settlements grew up along the Saline: the Grande Saline, located near the mouth of the creek, and the Petite Saline, located at the upper end of the creek, along a tributary. The purpose of the settlement was the manufacturing of salt which was used for meat preservation, skin tanning, and fur processing. Water from the salt springs was boiled in ovens the French built; when the water boiled away, the salt remained. Spanish Colonial authorities also set up a post at La Saline in 1788.[7] By 1800, French and Americans (Kentuckians) extracting salt from the Saline had set up four or five furnaces used for boiling off the salt for extraction, earning La Saline the name 'La Saline Ensanglantèe' (The Bloody Saline). These men were sending approximately thirty-five hundred barrels of salt to New Orleans each year.[8] As well as producing salt, La Saline’s location along the Mississippi River meant that it served as a lead-shipping point. Lead from Mine la Motte, opened in the 1720s, came by animal or cart over ridge roads and then down the Saline River Valley to its mouth at La Saline to be loaded on Mississippi River boats.[9]

In the early 19th century salt was being produced in southern Illinois along the Ohio River, making salt production in La Saline decline. In 1822, some seventeen workers were still using 100-150 kettles to extract salt, but by 1825, all production had ceased. As a village without any economic base and with efforts to make it a district post having failed, La Saline depopulated.[10]

Population

The earliest inhabitants of La Saline were French colonialists who worked to produce salt. Eventually, Americans poured in to produce salt as well. In the 1797 census, Americans dominated with twenty-eight households. Five other nationalities were represented: French, French Canadian, Creole, Irish and Scottish. Four different religions were identified: Anglican (twenty-three households), Catholic (eleven households), Presbyterian (five households), and Anabaptist (two households). In 1804 La Saline was reported to have had 59 inhabitants. The population was always small, with a temporary and diverse population comprising more single men than families.[11]

Layout

La Saline was an unplanned French village, which simply grew up amorphously without any spatial coordination. Typical of such villages were a small number of cabins scattered along a creek and road with corn plots surrounding gardens. There were no surveyed boundaries to separate tracts of land. As the main economic activity was salt-extraction and not agriculture, large tracts of farmland was not usual.[12]

Geography

La Saline was located on the Mississippi River at the mouth of Saline Creek, opposite of Kaskaskia Island, roughly six miles south of Sainte Genevieve.[13][14]

References

- Landmarkhunter.com

- André Pénicaut (1988). "Fleur de Lys and Calumet". ISBN 9780817304140. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Dr. Elizabeth M. Scott, Excavations and Research at Ste. Genevieve, Missouri http://lilt.ilstu.edu/emscot2/history.html Archived 2012-06-09 at the Wayback Machine

- State Historical Society of Missouri: Ste. Genevieve County http://shs.umsystem.edu/manuscripts/ramsay/ramsay_sainte_genevieve.html

- André Pénicaut (1988). "Fleur de Lys and Calumet". ISBN 9780817304140. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - William E. Foley (1989). "The Genesis of Missouri: From Wilderness Outpost to Statehood". University of Missouri Press: 24. ISBN 9780826207272.

la saline missouri.

Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Dr. Elizabeth M. Scott, Excavations and Research at Ste. Genevieve, Missouri http://lilt.ilstu.edu/emscot2/history.html Archived 2012-06-09 at the Wayback Machine

- William E. Foley (1989). "The Genesis of Missouri: From Wilderness Outpost to Statehood". University of Missouri Press: 24. ISBN 9780826207272.

la saline missouri.

Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - André Pénicaut (1988). "Fleur de Lys and Calumet". ISBN 9780817304140. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Walter A. Schroeder (2002). "Opening the Ozarks: A Historical Geography of Missouri's Ste. Genevieve District, 1760-1830". ISBN 9780826263063. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Walter A. Schroeder (2002). "Opening the Ozarks: A Historical Geography of Missouri's Ste. Genevieve District, 1760-1830". ISBN 9780826263063. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Walter A. Schroeder (2002). "Opening the Ozarks: A Historical Geography of Missouri's Ste. Genevieve District, 1760-1830". ISBN 9780826263063. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - André Pénicaut (1988). "Fleur de Lys and Calumet". ISBN 9780817304140. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Dr. Elizabeth M. Scott, Excavations and Research at Ste. Genevieve, Missouri http://lilt.ilstu.edu/emscot2/history.html Archived 2012-06-09 at the Wayback Machine