Kumgangsan Electric Railway

The Kŭmgangsan Electric Railway, later known as the Kŭmgangsan Line, was a railway line that formerly ran between Ch'ŏrwŏn to Naegŭmgang, on the inner side of Mount Kŭmgang.[1] At Ch'ŏrwŏn, the line connected to the Kyŏngwŏn Line of the Chosen Government Railway (Sentetsu)[2] the Kyŏngwŏn Line was split between Korail's Gyeongwon Line in South Korea and the Kangwŏn Line of the Korean State Railway.[3]

| |

Native name | 금강산 전기 철도 주식회사 (Korean) 金剛山電気鐵道株式会社 (Japanese) |

|---|---|

Romanized name | Kŭmgangsan Chŏn'gi Ch'ŏldo Chusikhoesa(Korean) Kongōsan Denki Tetsudō Kabushiki Kaisha (Japanese) |

| Kabushiki kaisha | |

| Industry | Railway, electric utility |

| Fate | Merged |

| Successor | Kyŏngsŏng Electric Co. |

| Founded | 16 December 1919 |

| Founder | Taminosuke Kume |

| Defunct | 1 January 1942 |

| Headquarters | 655-pŏnji, Oech'ŏn-ri, Ch'ŏrwŏn-gun, Kangwŏn-do (HQ) 4-Banchi, Nishi-Ginza 7-Chōme, Chūō-ku, Tōkyō (branch) Wangsim-dong, Sŏngdong-gu, Kyŏngsŏng (branch), |

| Kŭmgangsan Electric Line | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Naegŭmgang Station on the Kŭmgangsan Electric Railway | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Overview | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other name(s) | Kŭmgangsan Line (금강산선, 金剛山線) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Native name | 금강산전기선 (金剛山電氣線) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Type | Heavy rail, Passenger/Freight Regional rail | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Status | Closed | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Locale | Gangwon (South Korea) Kangwon (North Korea) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Termini | Cheorwon Naegŭmgang | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Stations | 28 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Operation | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Opened | Stages between 1924–1931 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Closed | 1950 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Owner | Kŭmgangsan Electric Railway Co. Ltd. (1924−1942) Kyŏngsŏng Electric Co. Ltd. (1942–1945) Korean State Railway (1945−1950) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Operator(s) | Kŭmgangsan Electric Railway Co. Ltd. (1924−1942) Kyŏngsŏng Electric Co. Ltd. (1942–1945) Korean State Railway (1945−1950) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Depot(s) | Ch'ŏrwŏn | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Technical | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Line length | 116.6 km (72.5 mi) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Number of tracks | Single track | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Track gauge | 1,435 mm (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in) standard gauge | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrification | 1.5 kV DC Overhead lines | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kumgangsan Electric Railway | |

| Hangul | 금강산전기철도 |

|---|---|

| Hanja | 金剛山電氣鐵道 |

| Revised Romanization | Geumgangsan Jeongi Cheoldo |

| McCune–Reischauer | Kŭmgangsan Chŏn'gi Ch'ŏldo |

| Other name | |

| Hangul | 금강산선 |

| Hanja | 金剛山線 |

| Revised Romanization | Geumgangsan-seon |

| McCune–Reischauer | Kŭmgangsan-sŏn |

Similar in many respects to the Alishan Forest Railway in Taiwan,[4] the railway was built with the aim of turning the Mount Kŭmgang area into a major tourist destination.[1] Mount Kŭmgang had already been one of the Korean Peninsula's most famous tourist destinations, but the terrain and location made access very difficult; the opening of the Kŭmgangsan Electric Railway overcame this, and turned the area into a booming tourist spot.[5]

Originally opened in 1924 by the Kŭmgangsan Electric Railway Co., Ltd. (Korean: 금강산전기철도 주식회사 Kŭmgangsan Chŏn'gi Ch'ŏldo Chusikhoesa; Japanese: 金剛山電気鉄道株式会社 Kongōsan Denki Tetsudō Kabushiki Kaisha), the 116.6 km (72.5 mi)[1] line held the distinction of being the first[1] as well as the longest electrified mainline railway in Korea,[6] Hydroelectric power from dams constructed along the line was used to supply power to the railway,[1] which made use of Japan's latest technological capabilities of the time.[5] The company's headquarters were located in Oech'ŏn-ri in Ch'ŏrwŏn-gun, and it had branch offices in Tokyo in Japan, as well as in Gyeongseong (Seoul).[4]

After the end of the Pacific War and the subsequent partition of Korea, the entirety of the line, being north of the 38th parallel, was taken over by North Korea's Korean State Railway, which called it the Kŭmgangsan Line, operating it until the outbreak of the Korean War in 1950.[7] The line was destroyed during the war, and the ceasefire line split the line between North and South Korea, and it remains abandoned ever since.

History

Formation of the Company (1918 to 1924)

Although the Mount Kŭmgang area had long been one of the most famous places in Korea for mountain sightseeing,[1] access was difficult due to the severe topography and poor roads.[5] In April 1918, Taminosuke Kume (久米民之助) visited the area and, having been immediately taken with it, believed that a railway to the area would have great potential not only for the development of tourism, but of agriculture and mining as well.[4] Kume, who had designed the Main Gate Iron Bridge at the Tokyo Imperial Palace, as well as had undertaken construction work for the Chosen Government Railway (Sentetsu), the South Manchuria Railway, the Taiwan Government Railway, and several railways in Japan,[4] sent railway engineer Togo Ōgawa in July 1918 to undertake an in-depth survey of the area.[4]

As the west side of the Mount Kŭmgang area is much less steep than the eastern side, Kume's attention focussed there, eventually deciding that the new line should be built from Ch'ŏrwŏn on Sentetsu's Kyŏngwŏn Line. Although geography and topography did play a role in the decision to build an electrified rail line, the primary motivation for the electrification was that the company was the possibility of constructing a number of hydroelectric power plants in the Kumgangsan area using the pumped-storage system - which at the time counted as advanced technology.[4]

The Chosen Hydropower Company (朝鮮水力電気株式会社, Chōsen Suiryokudenki Kabushiki Kaisha; 조선 수력전기 주식회사, Chosŏn Suryŏgjŏn'gi Chusikhoesa) had held the water rights to the rivers in the area. Kume thus had to acquire these rights, and after giving a detailed proposal to Katsujiro Okamoto, the Chief of the Electricity Division of the Communications Bureau of the Government-General of Korea appointed by Terauchi Masatake, the transfer of rights was approved. Okamoto later became Senior Managing Director of the Kŭmgangsan Electric Railway, serving in that role from 1931 until his death in 1938.[4]

Kume then set out to gather others to support and promote the project. Kyōhei Magoshi (馬越恭平), who had formerly been president of the Mitsui Group's Dai-Nippon Beer (predecessor of today's Sapporo Brewery and Asahi Breweries), became a promoter of the railway, and later became its second president.[4] Sakajirō Furukawa, designer of the Sasako Tunnel on the Chūō Main Line in Japan,[8] former president of the Japan Society of Civil Engineers, and who had had extensive railway experience working with the Japanese Government Railways, the Chinese Eastern Railway, and the South Manchuria Railway also joined on, eventually becoming the railway's third president after the death of Kyōhei Magoshi.[4]

With a group finally in place, on 25 March 1919, an application was submitted to the Government-General of Korea for permission to build the railway, along with an application for subsidies, and on 25 June applications for permission to build the necessary power plants were submitted. On 11 August 1919, all of these applications were approved, clearing the way for the realisation of the railway project.[4]

On 22 August 1919 a meeting was held for the organisation of the Kŭmgangsan Electric Railway Company, Ltd., and 100,000 shares were issued to raise funds for the project, of which 20,000 were allocated for the recruitment of general investors. The economic boom and the optimism of the post-First World War period played a major role in the great interest in these shares.[4] Finally, on 16 December 1919 the general meeting to establish the Kŭmgangsan Electric Railway Company, Ltd. Taminosuke Kume was elected president, and the company was officially registered on 22 December.[4]

In September 1920, construction of the tunnels necessary for the pumped-storage system for the hydroelectric dams began, in June 1921 construction of the dams began, and in September 1921 construction of the railway was launched. Although the line was initially planned to be built to the 1,067 mm (3 ft 6.0 in) cape gauge in standard use in Japan, under Furukawa's guidance it was changed to standard gauge in 1921 to allow for direct interchange with Sentetsu.[4] In 1923 the first phase of construction of the railway and the hydropower stations was completed, and the opening of the line for revenue operation was scheduled for November 1923. However, the Great Kantō earthquake of that year destroyed the electric generators for the trains which had been ordered from Shibaura Manufacturing in Tokyo, setting the plans back. To compensate, steam locomotives and passenger coaches were borrowed from the South Manchuria Railway, and with these, revenue service was started on the 28.8 km (17.9 mi) section from Ch'ŏrwŏn and Kimhwa on 1 August 1924.[4] Electrification of the line was completed in October, and operation of electric trains commenced on 27 October of that year, with both steam and electric trains running until 1 January 1925.[4]

As of March 1924, the Kŭmgangsan Electric Railway Company was the third largest of the 39 electric utilities in all Korea.[4]

Opening of the Railway and its Heyday (1924 to 1942)

The Government-General of Korea had a system of subsidies that it offered to promote the establishment of privately owned railways in order to improve the transportation system of the Korean peninsula; naturally, the Kŭmgangsan Electric Railway also received these subsidies. These were originally supposed to be for a period of ten years from the start of construction, but in 1921 this was extended to 15 years, and then in 1939, for certain railways this was extended to 25 years. Thus the Kŭmgangsan Electric Railway, which began construction in 1921, received subsidies from the Government-General all the way until the end of Japanese rule. For the Kŭmgangsan Electric Railway, whose operating profits were initially not as high as had been expected, these subsidies proved to be of great significance.[4]

Although the construction of the hydroelectric power stations and the railway itself proceeded smoothly despite the severe winter climate and the difficult terrain, two significant difficulties surfaced to present challenges to the Kŭmgangsan Electric Railway. The worldwide economic depression affected Japan and Korea along with the rest of the world, and though the company's shares were quickly bought up, the financial troubles of the investors led to about 7,000 shares being bought back by the company's president and executives; the directors went to great lengths to ensure the survival of the company, to the extent that president Taminosuke Kume sold his estate in Yoyogi for 2 million yen.[4]

After the opening of the initial section from Ch'ŏrwŏn to Kimhwa, construction of the line proceeded in stages.

| Date | Section | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1 August 1924 | Chŏrwŏn–Kimhwa | 28.8 km (17.9 mi) |

| 30 November 1925 | Kimhwa–Kŭmsŏng | 22.2 km (13.8 mi) |

| 15 September 1926 | Kŭmsŏng–Tangam | 8.6 km (5.3 mi) |

| 1 September 1927 | Tangam–Changdo | 8.0 km (5.0 mi) |

| 15 April 1929 | Changdo–Hyŏlli | 15.1 km (9.4 mi) |

| 25 September 1929 | Hyŏlli–Hwagye | 12.0 km (7.5 mi) |

| 15 May 1930 | Hwagye–Kŭmganggu (Malhwiri) | 13.3 km (8.3 mi) |

| 1 July 1931 | Kŭmganggu–Naegŭmgang | 8.6 km (5.3 mi) |

Construction of the Tanpallyŏng Tunnel began on 15 June 1928 and was completed on 15 September 1929.[4]

The Kŭmgangsan Electric Railway's 116.6 km (72.5 mi) line finally reached Naegŭmgang on 1 July 1931, with trains over the entire length of the route beginning on that day. However, president Kume failed to see the realisation of his dream, having died on 24 May 1931.[4] He was succeeded as president by Kyōhei Magoshi. A station was opened at South Changdo on 1 May 1936.[9]

In addition to 140,000 additional shares being issued in November 1926, a further 240,000 shares of 50 yen per share value were issued in 1932. Besides the railway, the company was also engaged in business as an electric utility, supplying electricity from its power plants to the area. Total income for the first half of 1931 was ¥843,168.2 sen, of which ¥248,760.30 was profit, ¥125,116.19 was carryover, and ¥477,175.12 was government subsidies - and ¥160,000 of the profits went straight to repaying interest on bonds and loans. The depression affected all the private railways in Korea. A number of them ended up being nationalised by the Railway Bureau and absorbed into Sentetsu, and for a time the nationalisation of the Kŭmgangsan Electric Railway was considered, too.[4]

By the mid 1930s, however, the economy turned around, and both passenger and freight transport along the line was booming. Tourists flocked to the railway, taking advantage of the available single and group tours, and in 1936 the line carried approximately 154,000 passengers.[10] The development of industries in the region also played a large part in the company's turnaround, as several quarries were opened along the line, along with iron sulphide (chalcopyrite) mines around Changdo. By 1939, profits just from railway income exceeded expenditures, and Taminosuke Kume's vision seemed to have finally come to fruition.[4]

Flooding was a major problem faced by the railway. Flood damage occurred in 1925, 1929, 1930, 1933, and 1936, and power generation facilities, power transmission facilities, and the railway were damaged on numerous occasions. In 1936, leakage occurred at the main power plant, Chungdae-ri Power Station which hindered the ability to generate power. Senior Managing Director Keijirō Okamoto ordered large-scale renovation work to be done. This was completed in 1937, restoring the power generation capabilities completely.[4]

Plans were drawn up to build a new line from Malhwiri on the mainline to Oegŭmgang on Sentetsu's Donghae Bukbu Line[11] (today called Kŭmgangsan Ch'ŏngnyŏn Station on the Korean State Railway's Kŭmgangsan Ch'ŏngnyŏn Line[3]). However, due to the ruggedness of the eastern side of the mountains, as well as the political situation after the Sino-Japanese War and the outbreak of the Pacific War, these plans were never realised.[4]

Wartime Merger and the End of the War (1942 to 1945)

The "glory days" of the late 1930s and the early 1940s made the future of the Kŭmgangsan Electric Railway look bright. However, this was abruptly cut short by the outbreak of the Pacific War.

As early as 1931, there were plans to consolidate the various electric utilities of the central Chungbu region of Korea, in which the Kŭmgangsan Electric Railway was located, into a single company. However, President Ōhashi of the Kyŏngsŏng Electric Co. was strongly opposed to the merger due to the fact that the Kŭmgangsan Electric Railway was receiving government subsidies for railway projects, and he felt that this could bring about unnecessary interference from the Government-General.[4]

However, the outbreak of the war changed circumstances, and wartime considerations led to the merger of all electric utilities on the Korean Peninsula into four regional companies, north, central, west, and south. The Kŭmgangsan Electric Railway was the most powerful of the companies to be merged in the central region, and so its merger with the Kyŏngsŏng Electric Company was the last to take place. The Kŭmgangsan Electric Railway Company was absorbed by the Kyŏngsŏng Electric Company on 1 January 1942, and from then on, the railway line was known as the Kŭmgangsan Electric Line of the Kyŏngsŏng Electric Company.[4]

When Sentetsu began to implement its plans to electrify its Kyŏngwŏn, Kyŏnggyŏng and Kyŏngin lines at the end of the 1930s,[12] electric locomotives were ordered from Mitsubishi and Toshiba.[13][14] The first DeRoI-class electric locomotive was delivered to Sentetsu in June 1943,[15] however, none of Sentetsu's planned electrification projects had been completed by then. Therefore, as the only electrified standard gauge railway line in Korea at the time, Sentetsu carried out the first tests of DeRoI-1 on the Kŭmgangsan Electric Line,[12] even though the Kŭmgangsan line was electrified at 1,500 V DC and the locomotives were designed to operate on 3,000 V DC.[14]

By 1944, Japan's situation in the war had deteriorated considerably. Having been used almost exclusively for tourist use, the 49.0 km (30.4 mi) Changdo−Naegumgang section was deemed unimportant and was closed on 1 October 1944.[16] The section was dismantled, with rails and other useful elements being removed for reuse on Sentetsu lines more important to the war effort.[4] However, the Ch'ŏrwŏn−Changdo section remained in use to continue exploiting the iron sulphide deposits at Changdo. All operations on the Kŭmgangsan line were suspended on 15 August 1945.[4]

After Liberation (1945 to 1950)

After the end of the Pacific War, Korea was partitioned into a Soviet and an American zone of occupation, with the Soviet zone eventually becoming North Korea, and the American zone becoming South Korea. This partition left the Kŭmgangsan Line located entirely within the Soviet zone of occupation, and it was nationalised along with all other railways in the zone on 10 August 1946.[17] The Korean State Railway, which had been formed as the DPRK's rail transport provider, reopened the Ch'ŏrwŏn−Changdo line and, calling it the Kŭmgangsan Line, operated trains along it until September 1950.[7]

The line was in large part destroyed by the Korean War, and the Military Demarcation Line established by the ceasefire in 1953 led to the division of the line between the two Koreas, as the armistice line ran between the stations of Kwangsam and Haso; everything south of Kwangsam ended up in South Korea, and everything north of Haso ended up in the DPRK.[4] Although service on the DPRK's portion of the former Kyŏngwŏn Line was restored after the war (becoming today's Kangwŏn Line[3]), the Kŭmgangsan Line was never rebuilt.[4]

Present Situation of the Line

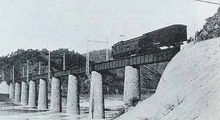

As the it is bisected by the MDL and the DMZ, it is difficult to access the remains of the South Korean portion of the line. However, the Hant'an'gang Bridge built in 1926 still stands, and is designated as South Korea's "Registered Cultural Property No. 112". Poles to support the overhead catenary are still in place on the bridge, and the bridge can be accessed on foot.[10]

The section on the Northern side is partially submerged as a result of the construction of the Imnam Dam, but some traces, such as bridge piers, can still be found, and certain segments of the right of way can be seen in aerial and satellite photos.[18]

Route information

- Route length: 116.6 km (72.5 mi)

- Operating agency:

- 1924-1942: Kŭmgangsan Electric Railway Co. Ltd.

- 1942-1945: Kyŏngsŏng Electric Co. Ltd.

- 1945-1950: Korean State Railway

- Gauge: 1,435 mm (4 ft 8.5 in)

- Operation: Left hand running

- Number of stations: 28

- Double tracked: none

- Electrification: 1500 V DC overhead line

The entire line was built to 1,435 mm (4 ft 8.5 in) standard gauge and was electrified with 1,500 V DC, with current collection taking place via pantographs from the catenary.[7]

Between Tanballyŏng and Malhwiri was a significant switchback, which has since been converted to a road.[1]

| Distance | Station name | Former name | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Distance (Total; km) |

Distance (S2S; km) |

(Transcribed) | (Chosŏn'gŭl (Hanja)) | (Transcribed) | (Chosŏn'gŭl (Hanja)) | (Japanese) | Connections |

| 0.0 | 0.0 | Ch'ŏrwŏn | 철원 (鉄原) | Tetsugen | Sentetsu Kyŏngwŏn Line/KSR Kangwŏn Line. Closed 1950. ROK since 1953. | ||

| 1.6 | 1.6 | Sayo | 사요 (四要) | Shiyō | Closed 1950. ROK since 1953. | ||

| 6.0 | 2.8 | Tongch'ŏrwŏn | 동철원 (東鉄原) | Higashi-Tetsugen | Closed 1950. ROK since 1953. | ||

| 10.3 | 4.3 | Yangji | 양지 (陽地) | Yōji | Closed 1950. ROK since 1953. | ||

| 14.2 | 3.9 | Igil | 이길 (二吉) | Jikitsu | Closed 1950. ROK since 1953. | ||

| 17.5 | 3.3 | Chŏngyŏn | 정연 (亭淵) | Jōen | Closed 1950. ROK since 1953. | ||

| 21.5 | 4.0 | Yugok | 유곡 (楡谷) | Yukoku | Closed 1950. ROK since 1953. | ||

| 24.5 | 3.0 | Kŭmgok | 금곡 (金谷) | Kingoku | Closed 1950. ROK since 1953. | ||

| 28.8 | 4.3 | Kimhwa | 김화 (金化) | Kinka | Closed 1950. ROK since 1953. | ||

| 33.0 | 4.2 | Kwangsam | 광삼 (光三) | Kōsan | Closed 1950. ROK since 1953. | ||

| 36.3 | 3.3 | Haso | 하소 (下所) | Kaso | Closed 1950. DPRK since 1945. | ||

| 40.1 | 3.8 | Haengjŏng | 행정 (杏亭) | Gyōjō | Closed 1950. DPRK since 1945. | ||

| 45.8 | 5.7 | Paeg'yang | 백양 (白楊) | Hakuyō | Closed 1950. DPRK since 1945. | ||

| 51.0 | 5.2 | Kŭmsŏng | 금성 (金城) | Kinjō | Closed 1950. DPRK since 1945. | ||

| 54.0 | 3.0 | Kyŏngp'a | 경파 (慶坡) | Kyōha | Closed 1950. DPRK since 1945. | ||

| 59.6 | 5.6 | T'an'gam | 탄감 (炭甘) | Tankan | Closed 1950. DPRK since 1945. | ||

| 65.6 | 6.0 | Namch'angdo | 남창도 (南昌道) | Nanshōdō | Closed 1950. DPRK since 1945. | ||

| 67.6 | 2.0 | Ch'angdo | 창도 (昌道) | Shōdō | Closed 1950. DPRK since 1945. | ||

| 75.3 | 7.7 | Kisŏng | 기성 (岐城) | Kijō | Closed 1944. DPRK since 1945. | ||

| 82.7 | 7.4 | Hyŏlli | 현리 (県里) | Kenri | Closed 1944. DPRK since 1945. | ||

| 90.0 | 7.3 | Top'a | 도파 (桃坡) | Tōha | Closed 1944. DPRK since 1945. | ||

| 94.7 | 4.7 | Hwagye | 화계 (花渓) | Kakei | Closed 1944. DPRK since 1945. | ||

| 99.3 | 4.6 | Oryang | 오량 (五両) | Goryō | Closed 1944. DPRK since 1945. | ||

| 104.8 | 5.5 | Tanballyŏng | 단발령 (断髪嶺) | Danpatsuryō | Closed 1944. DPRK since 1945. | ||

| 108.0 | 3.2 | Malhwiri | 말휘리 (末輝里) | Kŭmganggu | 금강구 (金剛口) | Kongōkō | Closed 1944. DPRK since 1945. |

| 112.4 | 4.4 | Pyŏngmu | 병무 (並武) | Byōmu | Closed 1944. DPRK since 1945. | ||

| 116.6 | 4.2 | Naegŭmgang | 내금강 (内金剛) | Naikongō | Closed 1944. DPRK since 1945. | ||

Operation

Right from the start, the railway's purpose was the opening of Mount Kŭmgang to mass tourism. As such, when the trains from Ch'ŏrwŏn to Kimwha began operation, a connecting bus service from Kimhwa to Naegŭmgang was begun at the same time. As the rail line was extended in stages to Kŭmsŏng, T'an'gam, Changdo, Hyŏlli, Hwagye, and Kŭmganggu (later Malhwiri), the bus run was shortened in turn, beginning at the then-current terminus of the railway. When the railway was completed to Naegŭmgang, this bus service was abolished.[4] The Korea Expo held from 12 September to 31 October 1929 played a major role in establishing the Kŭmgangsan Electric Railway, carrying a large number of Korean tourists to Mount Kŭmgang. After the line was completed to Naegŭmgang, tour packages were put on offer in Japan.[4]

Service on the trains was initially third-class only, until on 2 August 1931, a month after the opening of the last section of the line to Naegŭmgang, second-class service was inaugurated. During the tourist season, four daily round trips from Ch'ŏrwŏn to Naegŭmgang were operated, along with two or three round trips on the Ch'ŏrwŏn−Changdo and Ch'ŏrwŏn−Kimwha sections. In the off season, there were three daily return trips between Ch'ŏrwŏn and Naegŭmgang. The trip between Ch'ŏrwŏn and Naegŭmgang took approximately four hours.[4] A ticket between Ch'ŏrwŏn and Naegŭmgang was 7.56 Korean yen - the equivalent of a sack of rice.[10]

During the tourist season, sightseeing busses operated from Naegŭmgang, and various sightseeing tours were offered, along with discounted tourist tickets. Occasional special trains were also run during the peak season. Between May and October, a direct service between Kyŏngsŏng (Seoul) and Naegŭmgang was operated, using a Sentetsu sleeping car.[1] This service was started in 1930 and operated until July 1941, when wartime measures caused the suspension of tourist operations.[4]

Passenger trains were made up of four-car electric trainsets with second- and third-class compartments in addition to baggage rooms. The Sentetsu through sleeper between Kyŏngsŏng and Naegŭmgang was attached to or detached from the electric trainset at Ch'ŏrwŏn.[19]

In addition to passenger traffic, the movement of freight was also an important source of revenue for the Kŭmgangsan Electric Railway, with shipments of ore making up the bulk of all transportation during the November−April off season. Most of the freight was iron sulphide being moved from the mines at Changdo to the Chosen Nitrogenous Fertilizer Company (朝鮮窒素肥料株式会社 Chōsen Chisso Hiryō Kabushiki Kaisha, 조선 질소 비료 주식회사 Joseon Jilso Biryo Jusikhoesa) factory in Hŭngnam. As the Kŭmgangsan Electric Railway didn't operate any electric locomotives, freight trains were hauled by the electric passenger trainsets.[4]

After the Liberation and the subsequent partition of Korea, the Korean State Railway resumed passenger and freight traffic on the remaining Ch'ŏrwŏn−Changdo section of the line until after the outbreak of the Korean War in 1950, but details of these operations are unknown.[20]

Rolling Stock

.jpg)

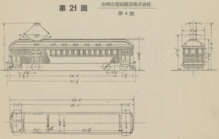

The Kŭmgangsan Electric Railway primarily operated self-powered electric railcars. There were a total of fourteen of various types that were built by Mantetsu's Shahekou Works, Sentetsu's Kyŏngsŏng Works, Tanaka Sharyou (a predecessor of today's Kinki Sharyo), Nippon Sharyō, and Kawasaki. In addition, the railway owned one non-powered passenger car and 28 freight cars.[7] No electric locomotives were owned, although a trial run with a Sentetsu DeRoI-class locomotive was carried out on the line.[12]

Trains were usually made up of three cars (DeRoHaNi plus two DeHa) in the off season, whilst in peak seasons, a fourth car was added. The addition of a Sentetsu sleeping car on the Kyŏngsŏng−Naegŭmgang overnight service counted as the fifth car on certain tourist-season trains.[19]

Several types of electric railcar were in use, including:

- DeHa 100-class - third class.[21]

- DeHaNi 100-class - third class with baggage compartment.[22] Built in 1931 by Nippon Sharyō.

- DeRoHaNi 100-class - second/third class with baggage compartment. Similar to the 2200 series electric railcars of the Sangū Express Electric Railway, and to the Shin Keihan Railway's P-6 class, five were built in 1931 by Nippon Sharyō.[7] One of these, number 102, is preserved at the P'yŏngyang Railway Museum.[23]

References

- travel-100years. "京元線 金剛山電気鉄道". www5f.biglobe.ne.jp.

- travel-100years. "京元線 鉄原". www5f.biglobe.ne.jp.

- Kokubu, Hayato (January 2007). 将軍様の鉄道 (Shōgun-sama no Tetsudō). Shinchōsha. p. 89–90. ISBN 978-4-10-303731-6.

- "金剛山電気鉄道について". www.norihuto.com.

- "金剛山電気鉄道 - まほろ市発何でもありのブログ".

- 柴みん. "金剛山電気鉄道 デハニ100型".

- "鉄道省革命事績館". www.2427junction.com.

- 『日本之精華』愛媛県之部 p.6

- "南昌道驛營業開始(남창도역영업개시)". NAVER Newslibrary.

- "鉄原安保観光". www.2427junction.com.

- "內金剛(내금강)에서外金剛(외금강)에 探勝(탐승)의電車(전차)를敷設(부설)". NAVER Newslibrary.

- Byeon, Seong-u (1999). 한국철도차량 100년사 [Korean Railways Rolling Stock Centennial] (in Korean). Seoul: Korea Rolling Stock Technical Corp.

- "デロイを探せ!(その4)発注数量と実生産数". ゴンブロ!(ゴンの徒然日記) (in Japanese). 8 November 2011.

- "松田新市三菱電機技師の戦中戦後の電気車設計". 北山敏和の鉄道いまむかし (in Japanese).

- "デロイを探せ!(その51)ソ連向けデロイの輸出許可申請書(その2)". ゴンブロ!(ゴンの徒然日記) (in Japanese). 18 March 2014.

- "韓国の廃線について". www.geocities.co.jp.

- Kokubu, Hayato (January 2007). 将軍様の鉄道 (Shōgun-sama no Tetsudō). Shinchōsha. p. 131. ISBN 978-4-10-303731-6.

- "内金剛周辺の金剛山電気鉄道の跡". www.norihuto.com.

- "金剛山電気鉄道デロハニ100型2,3等、手荷物合造電動制御車". www.geocities.jp.

- 《기차시간표》(1950년 4월 1일 개정), 북한 교통성 운수국 렬차부 편

- http://www.geocities.jp/dtn2301/km100.html 金剛山電気鉄道デハ100型3等電動制御車]

- "過去の参加イベント・頒布会での参加記念品や会場限定品のリストです。". mayworks.web.fc2.com.

- "平壌の鉄道事績館に保存されている 金剛山電気鉄道の電車". www.norihuto.com.

- Japanese Government Railways (1937), 鉄道停車場一覧. 昭和12年10月1日現在 (The List of the Stations as of 1 October 1937), Tokyo, p 515