Kolomyia

Kolomyia or Kolomyya, formerly known as Kolomea (Ukrainian: Коломия, romanized: Kolomyja, Polish: Kołomyja, Russian: Коломыя, German: Kolomea, Romanian: Colomeea, Yiddish: קאָלאָמיי), is a city located on the Prut River in Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast (province), in western Ukraine. It is administratively incorporated as a town of oblast significance and serves as the administrative centre of the surrounding Kolomyia Raion (district), which it is administratively not a part of. The city rests approximately halfway between Ivano-Frankivsk and Chernivtsi, in the centre of the historical region of Pokuttya, with which it shares much of its history. The population is 61,210 (2016 est.)[1].

Kolomyia Коломия Kołomyja • Colomeea | |

|---|---|

City Hall in Kolomyia | |

Flag  Coat of arms | |

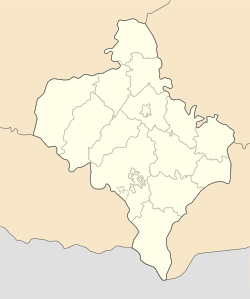

Kolomyia Location of Kolomyia  Kolomyia Kolomyia (Ukraine) | |

| Coordinates: 48°31′50″N 25°02′25″E | |

| Country Oblast Raion | Kolomyia Raion / Municipality |

| Area | |

| • Total | 41 km2 (16 sq mi) |

| Population (2016) | |

| • Total | 61,210 |

| • Density | 1,494/km2 (3,870/sq mi) |

| Website | www.ko.if.ua City's administrative statistics at Verkhovna Rada web-site |

The city is a notable railroad hub, as well as an industrial centre (textiles, shoes, metallurgical plant, machine works, wood and paper industry). It is a centre of Hutsul culture. Until 1925 the city was the most populous city in the region.

History

The settlement of Kolomyia was first mentioned by the Hypatian Chronicle[2] in 1240 and the Galician–Volhynian Chronicle in 1241 a time of the Mongol invasion of Rus'. Initially part of Kievan Rus', it later belonged to one of its successor states, the principality of Halych-Volhynia. On the order of Boroldai, the city fortress was burnt down in 1259. Since the mid 13th century it was known for its salt mining industry.[3]

Under Poland (1340–1498)

In 1340 it was annexed to Poland by King Casimir III following the Galicia–Volhynia Wars, along with the rest of the Kingdom of Russia. Sometime in the 1340s, another fortress was erected there.[2] In a short time the settlement became one of the most notable centres of commerce in the area. Because of that, the population rose rapidly.

Prior to 1353 there were two parishes in the settlement, one for Catholics and the other for Orthodox. In 1388 the king Władysław Jagiełło was forced by the war with the Teutonic Order to pawn the area of Pokuttya to the hospodar of Moldavia, Petru II. Although the city remained under Polish sovereignty, the income of the customs offices in the area was given to the Moldavians, after which time the debt was repaid. In 1412 the king erected a Dominican order monastery and a stone-built church there.

Development

In 1405 the town's city rights were confirmed and it was granted with the Magdeburg Law, which allowed the burghers limited self-governance.[4][5] This move made the development of the area faster and Kołomyja, as it was called then, attracted many settlers from many parts of Europe. Apart from the local Ukrainians and Poles, many Armenians, Jews, and Hungarians settled there. In 1411 the fortress-city was given away for 25 years to the Vlach Hospodar Olexander as a gift for his support in the war against Hungary.[5] In 1443, a year before his death, King Wladislaus II of Poland granted the city yet another privilege which allowed the burghers to trade salt, one of the most precious minerals of the Middle Ages.

Since the castle gradually fell into disarray, in 1448 King Casimir IV of Poland gave the castle on the hill above the town to Maria, widow of Eliah, voivode of Moldavia as a dowry. In exchange, she refurbished the castle and reinforced it. In 1456 the town was granted yet another privilege. This time the king allowed the town authorities to stop all merchants passing by the town, and force them to sell their goods at the local market. This gave the town an additional boost, especially as the region was one of three salt-producing areas in Poland (the other two being Wieliczka and Bochnia), both not far from Kraków.

The area was relatively peaceful for the next century. However, the vacuum after the decline of the Golden Horde started to be filled by yet another power in the area: the Ottoman Empire. In 1485 Sultan Beyazid II captured Belgorod and Kilia, two ports on the northern shores of the Black Sea. This became a direct threat to Moldavia. In search of allies, its ruler Ştefan cel Mare came to Kolomyia and paid homage to the Polish king, thus becoming a vassal of the Polish Crown. For the ceremony, both monarchs came with roughly 20,000 knights, which was probably the biggest festivity ever held in the town. After the festivity most knights returned home, apart from 3,000 under Jan Karnkowski, who were given to the Moldavian prince as support in his battles, which he won in the end. In 1490 the city was sacked by the riot of Ivan Mukha.[5]

Decline

However, with the death of Stefan of Moldova, the neighbouring state started to experience both internal and external pressure from the Turks. As a consequence of border skirmishes, as well as natural disasters, the town was struck by fires in 1502, 1505, 1513, and 1520.

Under Moldavia (1498–1531)

Władysław II Jagiełło, needing financial support in his battles against the Teutonic Knights, used the region as a guarantee in a loan which he obtained from Petru II of Moldavia, who thus gained control of Pokuttya in 1388. Therefore, it became the feudal property of the princes of Moldavia, but remained within the Kingdom of Poland.

After the Battle of the Cosmin Forest, in 1498, Pokuttia was conquered by Stephen the Great, annexed and retained by Moldavia until the Battle of Obertyn in 1531, when it was recaptured by Poland's hetman Jan Tarnowski, who defeated Stephen's son Petru Rareş. Minor Polish-Moldavian clashes for Pokuttia continued for the next 15 years, until Petru Rareş's death.

Polish – Ottoman wars

The following year, hetman Jan Tarnowski recaptured the town and defeated the Moldavians in the Battle of Obertyn. This victory secured the city's existence for the following years, but the Ottoman power grew and Poland's southern border remained insecure.

In 1589, the Turks crossed the border and seized Kolomyia almost immediately. All the burghers who had taken part in the defence were slaughtered, while the rest were forced to pay high indemnities.

The town was returned to Poland soon afterwards, but the city's growth lost its momentum.

In 1620, another Polono-Turkish war broke out. After the Polish defeat at Ţuţora, Kolomyia was yet again seized by the Turks. In 1626[5] the town was burned to the ground, while all of residents were enslaved in a jasyr.

After the war the area yet again returned to Poland. With the town in ruins, the starosta of Kamieniec Podolski fortress financed its reconstruction – slightly further away from the Prut River. The town was rebuilt, but never regained its power and remained one of many similar-scaled centres in the area.

Khmelnytskyi Uprising

During the Khmelnytskyi Uprising in 1648–54, the Kolomyia county became a centre of a peasant unrest (Pokuttya Uprising) led by Semen Vysochan.[2][6] The rebels' centre was a town of Otynia.[6] With the help of incoming Cossack forces, Vysochan managed to overtake the important local fortress of Pniv (today – a village of Nadvirna Raion) and eventually managed to take under its control most of cities and villages in the region providing great support for the advancing Cossack forces of Bohdan Khmelnytskyi.[6] Soon however with advancing Polish troops, Vysochan was forced to retreat to the eastern Podillya where he continued to fight under commands of Ivan Bohun and Ivan Sirko.[6]

In the 17th century the city's outskirts saw another peasant rebellion led by Oleksa Dovbush.[2] The rebels were known as opryshky.

Partition of Poland – Jewish history

As a result of the first of Partitions of Poland (Treaty of St. Petersburg dated 5 July 1772), Kolomyia[7] was attributed to the Habsburg Monarchy. More details about the history of Galicia can be read in the article Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria.

However, as it provided very little profit, Kolomyia was sold to the castellan of Bełz, Ewaryst Kuropatnicki, who became the town's owner. The magnate financed a new Our Lady's Church, but he lacked the financial means to accelerate the city's growth.

Prosperity returned to the town in the mid-19th century, when it was linked to the world through the Lemberg-Czernowitz railroad. In 1848 in Kolomyia was built a public library which was one of the first in eastern Galicia.[3] In 1861 there was opened a gymnasium where studied among others Petro Kozlaniuk, Vasyl Stefanyk, Marko Cheremshyna.[3] By 1882 the city had almost 24,000 inhabitants, including roughly 12,000 Jews, 6,000 Ruthenians, and 4,000 Poles. Until the end of that century, commerce attracted even more inhabitants from all over Galicia. There were established publishers and print houses.[3] Moreover, a new Jesuit Catholic church was built in Kolomyia, as it was called by German authorities, along with a Lutheran church built in 1874. By 1901 the number of inhabitants grew to 34,188, approximately half of them Jews.

20th century

In 1900 the Jewish population was 16,568, again nearly 50% of the town's population. The Jewish community had a Great Synagogue, and about 30 other synagogues. In 1910 Jews were prohibited from selling alcoholic beverages. In 1911 they were prohibited from salt and wine occupations.

After the outbreak of the Great War, the town saw fierce battles between the forces of the Russian Empire and Austria-Hungary. Jews were abused for supposedly supporting the Austrians, and many Jewish homes were ransacked and destroyed.

The Russian advance occupied the town in September 1914.

In 1915 the Austrians retook the town.

As a result of the collapse of Austria-Hungary, both the town itself and the surrounding region became disputed between renascent Poland and the West Ukrainian People's Republic.

Second Polish Republic

However, during the Polish-Ukrainian War of 1919, it was seized without a fight by forces of Romania, and handed over to Polish authorities. According to the Ukrainian Soviet Encyclopedia, it was taken over by the Polish bourgeoisie and land owners.[2] During the Polish-Bolshevik 1919 war in Ukraine, a Polish division under General Zeligowski tore through Bessarabia and Bukovina and stopped in Kolomyia during its winter march to Poland. Kolomyia was then temporarily occupied by the Romanians and the border was near the town (shtetl) Otynia between Stanislav and Kolomyia.

After the Polish-Soviet War it remained in Poland as a capital of a powiat within the Stanisławów Voivodship. By 1931 the number of inhabitants grew to over 41,000. The ethnic mixture was composed of Jews, Poles, Ukrainians (including Hutsuls), Germans, Armenians, and Hungarians, as well as of descendants of Valachians and other nationalities of former Austria-Hungary. With the development of infrastructure, the town became a major railroad hub, as well as the garrison city of the 49th Hutsul Rifle Regiment. In the interbellum period, every Thursday a market took place at the main square of the town. The town had a monument to Polish poet Franciszek Karpinski, a monument to Polish poet Adam Mickiewicz, and an obelisk near the town, located in a spot where in 1485 hospodar Stephen III of Moldavia paid tribute to king Kazimierz IV Jagiellon. In 1920-30s workers' strikes took place in the city, possibly organized by the Communist Party of Western Ukraine that was established in Kolomyia in 1923.[2]

In 1921 in Kolomyia was established a music school.[3]

After the outbreak of World War II with the Invasion of Poland of 1939, the town was thought of as one of the centres of Polish defence of the so-called Romanian Bridgehead.

Part of Soviet Union and World War II

However, the Soviet invasion from the east made these plans obsolete, and the town was occupied by the Red Army.

As a result of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, the occupied town became a part of the Soviet Union as a region of the Ukrainian SSR. The accession of the Western Ukraine to the Soviet Union (Reunion of Western Ukraine and USSR) – the adoption of the Soviet Union in Western Ukraine with the adoption of an Extraordinary Session V of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR Law "On the inclusion of the Western Ukraine in the Soviet Union to the reunification of the Ukrainian SSR" (1 November 1939) at the request of the Commission of the Plenipotentiary of the People's Assembly of Western Ukraine. The decision to file motions stipulated in the Declaration "On joining of Western Ukraine in the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic" was adopted by the People's Assembly of Western Ukraine in Lviv, 27 October 1939.

On 14 November 1939, the Third Extraordinary Session of the Supreme Soviet of USSR decided: "Accept Western Ukraine in the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, and thus reunite the great Ukrainian people in a unified Ukrainian state."

In 1940 part of the local population were arrested by the NKVD, and sent to the Gulag system or to various Soviet prisons among which were Polish, Ukrainians, Hungarians, and many others.

In 1941, the town was seized by Nazi Germany. During the German occupation most of the city's Jews were murdered by the German occupation authorities and by local Ukrainian nationalists who had organized a pogram before the arrival of the Germans and had prepared lists of Jews to be murdered for the Germans when they arrived[8]. Initial street executions of September and October 1941 took the lives of approximately 500 people. The following year the remaining Jews were massed in a local ghetto, and then murdered in various concentration camps, mostly in Bełżec. Several hundred Jews were kept as slave workers in a labour camp, and then murdered in 1943 in a forest near Sheparivtsi.

The Red Army liberated Kolomyia from the German invaders on 28 March 1944. Soon after that many construction workers, teachers, doctors, engineers and other skilled professionals began to arrive to restore the ruined city. They arrived from the eastern part of Ukraine and other parts of the Soviet Union.

During the Cold War the town was the headquarters of the 44th Rocket Division of the Strategic Rocket Forces, which had previously been the 73rd Engineer Brigade RVGK at Kamyshin. The division was disbanded on 31 March 1990.[9]

Under independent Ukraine (1991–present)

It is now a part of Ukraine, independent since 1991.

By the time of independence the vast majority of industrial enterprises of Kolomyia had closed or had been eliminated: Plant "Kolomyiasilmash", "Zahotzerno", plant "Elektroosnastka", factory "September 17", a shoe factory, a woodworking factory, plant KRP (complete switchgears),the printing house on Valova St.,a brush manufacturer, a weaving factory and many others. Also shut down were movie theatres; there had been four: Irchan movie theatre, Kirov movie theatre, movie theatre "Yunist" (Youth), and a summer theatre in the present Trylovskoho park (formerly named Kirov park). A film store of regional importance also closed down. As a result, many people found themselves unemployed, and many town residents felt forced to move abroad to find work. Those companies that have remained from the Soviet era barely function. These include a curtain factory, a paper mill, Metalozavod, Plant PRUT (programmable electronic educational terminals),a cheese factory, "Kolomyiasilmash", Kolomyia Plant management of building materials, Kolomyia Motor Company, a paper mill, a clothes factory on Valova St, a printing house on Mazepa St., and a canned fruit plant.

Most of these companies were widely known in the former Soviet Union and abroad, as they were highly advanced in terms of equipment, skilled workers, and engineering staff. These enterprises produced many products, with people working in several shifts, and providing the city with received significant tax revenues.

It is a sister city of Nysa in Poland, to which many of its former inhabitants had to move after the war.

Since late 2015, Kolomyia has been the headquarters of the Ukrainian 10th Mountain Brigade.[10]

Economy

- Kolomyiasilmash

- Factory of the 17 September

- Factory of construction materials

- Factory combine of household services

Culture

Kolomyia is famous for its Pysanka Museum, that was built in 2000.

The museum was opened on 23 September 2000, during the 10th International Hutsul festival. Director Yaroslava Tkachuk first came up with the idea of a museum in the shape of a pysanka, local artists Vasyl Andrushko and Myroslav Yasinskyi brought the idea to life. The museum is not only shaped like an egg (14 m in height and 10 m in diameter), but parts of the exterior and interior of the dome are painted to resemble a pysanka.

Location

- Regional orientation

Twin towns – sister cities

Notable people

- Myroslav Irchan (1897-1937), Ukrainian playwright

- Emanuel Feuermann (1902–1942), American cellist

- Eugene Frisch (1922-2011), American civil engineer

- Chaim Gross (1904–1991), American sculptor and educator

- Roman Hryhorchuk (born 1965), Ukrainian football player and manager

- Olena Iurkovska (born 1983), Ukrainian athlete, five-time Paralympic Champion and Hero of Ukraine[12][13][14][15]

- Mieczyslaw Jagielski (1924–1997), Polish politician and economist

- Franciszek Karpinski (1741–1825), Polish 17th century poet

- Hillel Lichtenstein (1814-1891), Hungarian rabbi

- Karl Maramorosch (1915–2016), Austrian-born American virologist, entomologist, and plant pathologist

- Dov Noy (born 1920), Israeli folklorist, recipient of the Israel Prize in 2004

- Stanislaw Ruziewicz (1889–1941), Polish mathematician

- Józef Sandel (1894–1962), Polish-Jewish art historian and critic, art dealer, and collector

- Abraham Nachman Hersz Schneider (1922-2007), destacado lawyer and judge in Argentina

- Olesya Stefanko (born 1988), Ukrainian pageant, finished 1st runner-up at the 2011 Miss Universe pageant (Ukraine's highest placement to date)

- Andrzej Zalucki (born 1941), Polish diplomat

- Jakiw Palij (1923–2019), Trawniki concentration camp guard who was the last known Nazi to have lived in the United States

See also

References

- "Чисельність наявного населення України (Actual population of Ukraine)" (PDF) (in Ukrainian). State Statistics Service of Ukraine. Retrieved 19 July 2016.

- Kolomyia at the Ukrainian Soviet Encyclopedia

- Verbylenko, H. Kolomyia (КОЛОМИЯ). Encyclopedia of History of Ukraine. 2007

- City's website

- Kolomea history

- Semen Vysochan. Ukrainians in the World.

- Atlas des peuples d'Europe centrale, André et Jean Sellier, 1991, p.88

- Megargee, Geoffrey (2012). Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos. Bloomington, Indiana: University of Indiana Press. p. Volume II, 790-702. ISBN 978-0-253-35599-7.

- 44th Missile Division

- На Прикарпатті створять нову гірську штурмову бригаду - Народна армія [In the mountainous Carpathian region will create new assault brigade]. na.mil.gov.ua (in Ukrainian). Narodna armiya. 22 September 2015. Archived from the original on 31 January 2016. Retrieved 31 January 2016.

- "Коломия уклала партнерські угоди з Дрокією та Ришканами". kolrada.gov.ua (in Ukrainian). Kolomyia. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- Results for Olena Iurkovska from the International Paralympic Committee (archived)

- (in Ukrainian) Юрковська Олена Юріївна, who-is-Who.ua

- (in Ukrainian) Документ 287/2006, Verkhovna Rada (3 April 2006)

- Viktor Yushchenko Decorates Paralympist Olena Yurkovska With Golden Star Order, Ukrinform (6 April 2006)

Further reading

- "Der Don Juan von Kolomea" (The Don Juan of Kolomyia), by Leopold von Sacher-Masoch

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Kolomyia. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kolomyia. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Kolomea. |

- http://ww2.gov.if.ua/kolomiyskiy/ua(in Ukrainian)

- http://nad.at.ua/news/istorija_mista_kolomiji(in Ukrainian)

- http://leksika.com.ua/19200421/ure/kolomiya (in Ukrainian)

- ntktv.ua, the city's television

- Історія Коломиї (in Ukrainian)

- kolomyya.org (in Ukrainian)

- pysanka.museum Pysanka Museum

- hutsul.museum Hutsul and Pokuttya National Folk Art Museum

- Heraldry and old pictures

- Picture gallery

- Kolomyia's Museum of Hutsul Folk Art

- New York-based Jewish organizations of exiles from Kolomyia

- JewishGen – The Kolomea Administrative District

- Memorial Book

- Photographs of Jewish sites in Kolomyia in the Jewish History in Galicia and Bukovina

- Kolomyya, Ukraine at JewishGen