Kolmogorov complexity

In algorithmic information theory (a subfield of computer science and mathematics), the Kolmogorov complexity of an object, such as a piece of text, is the length of a shortest computer program (in a predetermined programming language) that produces the object as output. It is a measure of the computational resources needed to specify the object, and is also known as algorithmic complexity, Solomonoff–Kolmogorov–Chaitin complexity, program-size complexity, descriptive complexity, or algorithmic entropy. It is named after Andrey Kolmogorov, who first published on the subject in 1963.[1][2]

The notion of Kolmogorov complexity can be used to state and prove impossibility results akin to Cantor's diagonal argument, Gödel's incompleteness theorem, and Turing's halting problem. In particular, no program P computing a lower bound for each text's Kolmogorov complexity can return a value essentially larger than P's own length (see section § Chaitin's incompleteness theorem); hence no single program can compute the exact Kolmogorov complexity for infinitely many texts.

Definition

Consider the following two strings of 32 lowercase letters and digits:

abababababababababababababababab, and4c1j5b2p0cv4w1x8rx2y39umgw5q85s7

The first string has a short English-language description, namely "write ab 16 times", which consists of 17 characters. The second one has no obvious simple description (using the same character set) other than writing down the string itself, i.e., "write 4c1j5b2p0cv4w1x8rx2y39umgw5q85s7" which has 38 characters. Hence the operation of writing the first string can be said to have "less complexity" than writing the second.

More formally, the complexity of a string is the length of the shortest possible description of the string in some fixed universal description language (the sensitivity of complexity relative to the choice of description language is discussed below). It can be shown that the Kolmogorov complexity of any string cannot be more than a few bytes larger than the length of the string itself. Strings like the abab example above, whose Kolmogorov complexity is small relative to the string's size, are not considered to be complex.

The Kolmogorov complexity can be defined for any mathematical object, but for simplicity the scope of this article is restricted to strings. We must first specify a description language for strings. Such a description language can be based on any computer programming language, such as Lisp, Pascal, or Java. If P is a program which outputs a string x, then P is a description of x. The length of the description is just the length of P as a character string, multiplied by the number of bits in a character (e.g., 7 for ASCII).

We could, alternatively, choose an encoding for Turing machines, where an encoding is a function which associates to each Turing Machine M a bitstring <M>. If M is a Turing Machine which, on input w, outputs string x, then the concatenated string <M> w is a description of x. For theoretical analysis, this approach is more suited for constructing detailed formal proofs and is generally preferred in the research literature. In this article, an informal approach is discussed.

Any string s has at least one description. For example, the second string above is output by the program:

function GenerateString2()

return "4c1j5b2p0cv4w1x8rx2y39umgw5q85s7"

whereas the first string is output by the (much shorter) pseudo-code:

function GenerateString1()

return "ab" × 16

If a description d(s) of a string s is of minimal length (i.e., using the fewest bits), it is called a minimal description of s, and the length of d(s) (i.e. the number of bits in the minimal description) is the Kolmogorov complexity of s, written K(s). Symbolically,

- K(s) = |d(s)|.

The length of the shortest description will depend on the choice of description language; but the effect of changing languages is bounded (a result called the invariance theorem).

Invariance theorem

Informal treatment

There are some description languages which are optimal, in the following sense: given any description of an object in a description language, said description may be used in the optimal description language with a constant overhead. The constant depends only on the languages involved, not on the description of the object, nor the object being described.

Here is an example of an optimal description language. A description will have two parts:

- The first part describes another description language.

- The second part is a description of the object in that language.

In more technical terms, the first part of a description is a computer program, with the second part being the input to that computer program which produces the object as output.

The invariance theorem follows: Given any description language L, the optimal description language is at least as efficient as L, with some constant overhead.

Proof: Any description D in L can be converted into a description in the optimal language by first describing L as a computer program P (part 1), and then using the original description D as input to that program (part 2). The total length of this new description D′ is (approximately):

- |D′| = |P| + |D|

The length of P is a constant that doesn't depend on D. So, there is at most a constant overhead, regardless of the object described. Therefore, the optimal language is universal up to this additive constant.

A more formal treatment

Theorem: If K1 and K2 are the complexity functions relative to Turing complete description languages L1 and L2, then there is a constant c – which depends only on the languages L1 and L2 chosen – such that

- ∀s. −c ≤ K1(s) − K2(s) ≤ c.

Proof: By symmetry, it suffices to prove that there is some constant c such that for all strings s

- K1(s) ≤ K2(s) + c.

Now, suppose there is a program in the language L1 which acts as an interpreter for L2:

function InterpretLanguage(string p)

where p is a program in L2. The interpreter is characterized by the following property:

- Running

InterpretLanguageon input p returns the result of running p.

Thus, if P is a program in L2 which is a minimal description of s, then InterpretLanguage(P) returns the string s. The length of this description of s is the sum of

- The length of the program

InterpretLanguage, which we can take to be the constant c. - The length of P which by definition is K2(s).

This proves the desired upper bound.

History and context

Algorithmic information theory is the area of computer science that studies Kolmogorov complexity and other complexity measures on strings (or other data structures).

The concept and theory of Kolmogorov Complexity is based on a crucial theorem first discovered by Ray Solomonoff, who published it in 1960, describing it in "A Preliminary Report on a General Theory of Inductive Inference"[3] as part of his invention of algorithmic probability. He gave a more complete description in his 1964 publications, "A Formal Theory of Inductive Inference," Part 1 and Part 2 in Information and Control.[4][5]

Andrey Kolmogorov later independently published this theorem in Problems Inform. Transmission[6] in 1965. Gregory Chaitin also presents this theorem in J. ACM – Chaitin's paper was submitted October 1966 and revised in December 1968, and cites both Solomonoff's and Kolmogorov's papers.[7]

The theorem says that, among algorithms that decode strings from their descriptions (codes), there exists an optimal one. This algorithm, for all strings, allows codes as short as allowed by any other algorithm up to an additive constant that depends on the algorithms, but not on the strings themselves. Solomonoff used this algorithm and the code lengths it allows to define a "universal probability" of a string on which inductive inference of the subsequent digits of the string can be based. Kolmogorov used this theorem to define several functions of strings, including complexity, randomness, and information.

When Kolmogorov became aware of Solomonoff's work, he acknowledged Solomonoff's priority.[8] For several years, Solomonoff's work was better known in the Soviet Union than in the Western World. The general consensus in the scientific community, however, was to associate this type of complexity with Kolmogorov, who was concerned with randomness of a sequence, while Algorithmic Probability became associated with Solomonoff, who focused on prediction using his invention of the universal prior probability distribution. The broader area encompassing descriptional complexity and probability is often called Kolmogorov complexity. The computer scientist Ming Li considers this an example of the Matthew effect: "…to everyone who has more will be given…"[9]

There are several other variants of Kolmogorov complexity or algorithmic information. The most widely used one is based on self-delimiting programs, and is mainly due to Leonid Levin (1974).

An axiomatic approach to Kolmogorov complexity based on Blum axioms (Blum 1967) was introduced by Mark Burgin in the paper presented for publication by Andrey Kolmogorov.[10]

Basic results

In the following discussion, let K(s) be the complexity of the string s.

It is not hard to see that the minimal description of a string cannot be too much larger than the string itself — the program GenerateString2 above that outputs s is a fixed amount larger than s.

Theorem: There is a constant c such that

- ∀s. K(s) ≤ |s| + c.

Uncomputability of Kolmogorov complexity

Theorem: There exist strings of arbitrarily large Kolmogorov complexity. Formally: for each n ∈ ℕ, there is a string s with K(s) ≥ n.[note 1]

Proof: Otherwise all of the infinitely many possible finite strings could be generated by the finitely many[note 2] programs with a complexity below n bits.

Theorem: K is not a computable function. In other words, there is no program which takes a string s as input and produces the integer K(s) as output.

The following indirect proof uses a simple Pascal-like language to denote programs; for sake of proof simplicity assume its description (i.e. an interpreter) to have a length of 1400000 bits. Assume for contradiction there is a program

function KolmogorovComplexity(string s)

which takes as input a string s and returns K(s); for sake of proof simplicity, assume the program's length to be 7000000000 bits. Now, consider the following program of length 1288 bits:

function GenerateComplexString()

for i = 1 to infinity:

for each string s of length exactly i

if KolmogorovComplexity(s) ≥ 8000000000

return s

Using KolmogorovComplexity as a subroutine, the program tries every string, starting with the shortest, until it returns a string with Kolmogorov complexity at least 8000000000 bits,[note 3] i.e. a string that cannot be produced by any program shorter than 8000000000 bits. However, the overall length of the above program that produced s is only 7001401288 bits,[note 4] which is a contradiction. (If the code of KolmogorovComplexity is shorter, the contradiction remains. If it is longer, the constant used in GenerateComplexString can always be changed appropriately.)[note 5]

The above proof uses a contradiction similar to that of the Berry paradox: "1The 2smallest 3positive 4integer 5that 6cannot 7be 8defined 9in 10fewer 11than 12twenty 13English 14words". It is also possible to show the non-computability of K by reduction from the non-computability of the halting problem H, since K and H are Turing-equivalent.[11]

There is a corollary, humorously called the "full employment theorem" in the programming language community, stating that there is no perfect size-optimizing compiler.

A naive attempt at a program to compute K

At first glance it might seem trivial to write a program which can compute K(s) for any s (thus disproving the above theorem), such as the following:

function KolmogorovComplexity(string s)

for i = 1 to infinity:

for each string p of length exactly i

if isValidProgram(p) and evaluate(p) == s

return i

This program iterates through all possible programs (by iterating through all possible strings and only considering those which are valid programs), starting with the shortest. Each program is executed to find the result produced by that program, comparing it to the input s. If the result matches the length of the program is returned.

However this will not work because some of the programs p tested will not terminate, e.g. if they contain infinite loops. There is no way to avoid all of these programs by testing them in some way before executing them due to the non-computability of the halting problem.

Chain rule for Kolmogorov complexity

The chain rule[12] for Kolmogorov complexity states that

- K(X,Y) ≤ K(X) + K(Y|X) + O(log(K(X,Y))).

It states that the shortest program that reproduces X and Y is no more than a logarithmic term larger than a program to reproduce X and a program to reproduce Y given X. Using this statement, one can define an analogue of mutual information for Kolmogorov complexity.

Compression

It is straightforward to compute upper bounds for K(s) – simply compress the string s with some method, implement the corresponding decompressor in the chosen language, concatenate the decompressor to the compressed string, and measure the length of the resulting string – concretely, the size of a self-extracting archive in the given language.

A string s is compressible by a number c if it has a description whose length does not exceed |s| − c bits. This is equivalent to saying that K(s) ≤ |s| − c. Otherwise, s is incompressible by c. A string incompressible by 1 is said to be simply incompressible – by the pigeonhole principle, which applies because every compressed string maps to only one uncompressed string, incompressible strings must exist, since there are 2n bit strings of length n, but only 2n − 1 shorter strings, that is, strings of length less than n, (i.e. with length 0, 1, ..., n − 1).[note 6]

For the same reason, most strings are complex in the sense that they cannot be significantly compressed – their K(s) is not much smaller than |s|, the length of s in bits. To make this precise, fix a value of n. There are 2n bitstrings of length n. The uniform probability distribution on the space of these bitstrings assigns exactly equal weight 2−n to each string of length n.

Theorem: With the uniform probability distribution on the space of bitstrings of length n, the probability that a string is incompressible by c is at least 1 − 2−c+1 + 2−n.

To prove the theorem, note that the number of descriptions of length not exceeding n − c is given by the geometric series:

- 1 + 2 + 22 + … + 2n − c = 2n−c+1 − 1.

There remain at least

- 2n − 2n−c+1 + 1

bitstrings of length n that are incompressible by c. To determine the probability, divide by 2n.

Chaitin's incompleteness theorem

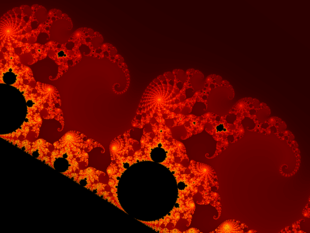

prog1(s), prog2(s). The horizontal axis (logarithmic scale) enumerates all strings s, ordered by length; the vertical axis (linear scale) measures Kolmogorov complexity in bits. Most strings are incompressible, i.e. their Kolmogorov complexity exceeds their length by a constant amount. 9 compressible strings are shown in the picture, appearing as almost vertical slopes. Due to Chaitin's incompleteness theorem (1974), the output of any program computing a lower bound of the Kolmogorov complexity cannot exceed some fixed limit, which is independent of the input string s.By the above theorem (§ Compression), most strings are complex in the sense that they cannot be described in any significantly "compressed" way. However, it turns out that the fact that a specific string is complex cannot be formally proven, if the complexity of the string is above a certain threshold. The precise formalization is as follows. First, fix a particular axiomatic system S for the natural numbers. The axiomatic system has to be powerful enough so that, to certain assertions A about complexity of strings, one can associate a formula FA in S. This association must have the following property:

If FA is provable from the axioms of S, then the corresponding assertion A must be true. This "formalization" can be achieved based on a Gödel numbering.

Theorem: There exists a constant L (which only depends on S and on the choice of description language) such that there does not exist a string s for which the statement

- K(s) ≥ L (as formalized in S)

can be proven within S.[13]:Thm.4.1b

Proof: The proof of this result is modeled on a self-referential construction used in Berry's paradox.

We can find an effective enumeration of all the formal proofs in S by some procedure

function NthProof(int n)

which takes as input n and outputs some proof. This function enumerates all proofs. Some of these are proofs for formulas we do not care about here, since every possible proof in the language of S is produced for some n. Some of these are complexity formulas of the form K(s) ≥ n where s and n are constants in the language of S. There is a procedure

function NthProofProvesComplexityFormula(int n)

which determines whether the nth proof actually proves a complexity formula K(s) ≥ L. The strings s, and the integer L in turn, are computable by procedure:

function StringNthProof(int n)

function ComplexityLowerBoundNthProof(int n)

Consider the following procedure:

function GenerateProvablyComplexString(int n)

for i = 1 to infinity:

if NthProofProvesComplexityFormula(i) and ComplexityLowerBoundNthProof(i) ≥ n

return StringNthProof(i)

Given an n, this procedure tries every proof until it finds a string and a proof in the formal system S of the formula K(s) ≥ L for some L ≥ n; if no such proof exists, it loops forever.

Finally, consider the program consisting of all these procedure definitions, and a main call:

GenerateProvablyComplexString(n0)

where the constant n0 will be determined later on. The overall program length can be expressed as U+log2(n0), where U is some constant and log2(n0) represents the length of the integer value n0, under the reasonable assumption that it is encoded in binary digits. Now consider the function f:[2,∞)→[1,∞), defined by f(x) = x − log2(x). It is strictly increasing on its domain, and hence has an inverse f−1:[1,∞)→[2,∞).

Define n0 = f−1(U)+1.

Then no proof of the form "K(s)≥L" with L≥n0 can be obtained in S, as can be seen by an indirect argument:

If ComplexityLowerBoundNthProof(i) could return a value ≥n0, then the loop inside GenerateProvablyComplexString would eventually terminate, and that procedure would return a string s such that

| K(s) | |||

| ≥ | n0 | by construction of GenerateProvablyComplexString | |

| > | U+log2(n0) | since n0 > f−1(U) implies n0 − log2(n0) = f(n0) > U | |

| ≥ | K(s) | since s was described by the program with that length |

This is a contradiction, Q.E.D.

As a consequence, the above program, with the chosen value of n0, must loop forever.

Similar ideas are used to prove the properties of Chaitin's constant.

Minimum message length

The minimum message length principle of statistical and inductive inference and machine learning was developed by C.S. Wallace and D.M. Boulton in 1968. MML is Bayesian (i.e. it incorporates prior beliefs) and information-theoretic. It has the desirable properties of statistical invariance (i.e. the inference transforms with a re-parametrisation, such as from polar coordinates to Cartesian coordinates), statistical consistency (i.e. even for very hard problems, MML will converge to any underlying model) and efficiency (i.e. the MML model will converge to any true underlying model about as quickly as is possible). C.S. Wallace and D.L. Dowe (1999) showed a formal connection between MML and algorithmic information theory (or Kolmogorov complexity).[14]

Kolmogorov randomness

Kolmogorov randomness defines a string (usually of bits) as being random if and only if it is shorter than any computer program that can produce that string. To make this precise, a universal computer (or universal Turing machine) must be specified, so that "program" means a program for this universal machine. A random string in this sense is "incompressible" in that it is impossible to "compress" the string into a program whose length is shorter than the length of the string itself. A counting argument is used to show that, for any universal computer, there is at least one algorithmically random string of each length. Whether any particular string is random, however, depends on the specific universal computer that is chosen.

This definition can be extended to define a notion of randomness for infinite sequences from a finite alphabet. These algorithmically random sequences can be defined in three equivalent ways. One way uses an effective analogue of measure theory; another uses effective martingales. The third way defines an infinite sequence to be random if the prefix-free Kolmogorov complexity of its initial segments grows quickly enough — there must be a constant c such that the complexity of an initial segment of length n is always at least n−c. This definition, unlike the definition of randomness for a finite string, is not affected by which universal machine is used to define prefix-free Kolmogorov complexity.[15]

Relation to entropy

For dynamical systems, entropy rate and algorithmic complexity of the trajectories are related by a theorem of Brudno, that the equality K(x;T) = h(T) holds for almost all x.[16]

It can be shown[17] that for the output of Markov information sources, Kolmogorov complexity is related to the entropy of the information source. More precisely, the Kolmogorov complexity of the output of a Markov information source, normalized by the length of the output, converges almost surely (as the length of the output goes to infinity) to the entropy of the source.

Conditional versions

The conditional Kolmogorov complexity of two strings is, roughly speaking, defined as the Kolmogorov complexity of x given y as an auxiliary input to the procedure.[18][19]

There is also a length-conditional complexity , which is the complexity of x given the length of x as known/input.[20][21]

See also

- Important publications in algorithmic information theory

- Berry paradox

- Code golf

- Data compression

- Demoscene, a computer art discipline whose certain branches are centered around the creation of smallest programs that achieve certain effects

- Descriptive complexity theory

- Grammar induction

- Inductive inference

- Kolmogorov structure function

- Levenshtein distance

- Solomonoff's theory of inductive inference

Notes

- However, an s with K(s) = n need not exist for every n. For example, if n is not a multiple of 7 bits, no ASCII program can have a length of exactly n bits.

- There are 1 + 2 + 22 + 23 + ... + 2n = 2n+1 − 1 different program texts of length up to n bits; cf. geometric series. If program lengths are to be multiples of 7 bits, even fewer program texts exist.

- By the previous theorem, such a string exists, hence the

forloop will eventually terminate. - including the language interpreter and the subroutine code for

KolmogorovComplexity - If

KolmogorovComplexityhas length n bits, the constant m used inGenerateComplexStringneeds to be adapted to satisfy n + 1400000 + 1218 + 7·log10(m) < m, which is always possible since m grows faster than log10(m). - As there are NL = 2L strings of length L, the number of strings of lengths L = 0, 1, …, n − 1 is N0 + N1 + … + Nn−1 = 20 + 21 + … + 2n−1, which is a finite geometric series with sum 20 + 21 + … + 2n−1 = 20 × (1 − 2n) / (1 − 2) = 2n − 1

References

- Kolmogorov, Andrey (1963). "On Tables of Random Numbers". Sankhyā Ser. A. 25: 369–375. MR 0178484.

- Kolmogorov, Andrey (1998). "On Tables of Random Numbers". Theoretical Computer Science. 207 (2): 387–395. doi:10.1016/S0304-3975(98)00075-9. MR 1643414.

- Solomonoff, Ray (February 4, 1960). "A Preliminary Report on a General Theory of Inductive Inference" (PDF). Report V-131. revision, Nov., 1960.

- Solomonoff, Ray (March 1964). "A Formal Theory of Inductive Inference Part I" (PDF). Information and Control. 7 (1): 1–22. doi:10.1016/S0019-9958(64)90223-2.

- Solomonoff, Ray (June 1964). "A Formal Theory of Inductive Inference Part II" (PDF). Information and Control. 7 (2): 224–254. doi:10.1016/S0019-9958(64)90131-7.

- Kolmogorov, A.N. (1965). "Three Approaches to the Quantitative Definition of Information". Problems Inform. Transmission. 1 (1): 1–7. Archived from the original on September 28, 2011.

- Chaitin, Gregory J. (1969). "On the Simplicity and Speed of Programs for Computing Infinite Sets of Natural Numbers". Journal of the ACM. 16 (3): 407–422. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.15.3821. doi:10.1145/321526.321530.

- Kolmogorov, A. (1968). "Logical basis for information theory and probability theory". IEEE Transactions on Information Theory. 14 (5): 662–664. doi:10.1109/TIT.1968.1054210.

- Li, Ming; Vitányi, Paul (2008). "Preliminaries". An Introduction to Kolmogorov Complexity and its Applications. Texts in Computer Science. pp. 1–99. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-49820-1_1. ISBN 978-0-387-33998-6.

- Burgin, M. (1982), "Generalized Kolmogorov complexity and duality in theory of computations", Notices of the Russian Academy of Sciences, v.25, No. 3, pp. 19–23.

- Stated without proof in: "Course notes for Data Compression - Kolmogorov complexity" Archived 2009-09-09 at the Wayback Machine, 2005, P. B. Miltersen, p.7

- Zvonkin, A.; L. Levin (1970). "The complexity of finite objects and the development of the concepts of information and randomness by means of the theory of algorithms" (PDF). Russian Mathematical Surveys. 25 (6). pp. 83–124.

- Gregory J. Chaitin (Jul 1974). "Information-theoretic limitations of formal systems" (PDF). Journal of the ACM. 21 (3): 403–434. doi:10.1145/321832.321839.

- Wallace, C. S.; Dowe, D. L. (1999). "Minimum Message Length and Kolmogorov Complexity". Computer Journal. 42 (4): 270–283. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.17.321. doi:10.1093/comjnl/42.4.270.

- Martin-Löf, Per (1966). "The definition of random sequences". Information and Control. 9 (6): 602–619. doi:10.1016/s0019-9958(66)80018-9.

- Galatolo, Stefano; Hoyrup, Mathieu; Rojas, Cristóbal (2010). "Effective symbolic dynamics, random points, statistical behavior, complexity and entropy" (PDF). Information and Computation. 208: 23–41. doi:10.1016/j.ic.2009.05.001.

- Alexei Kaltchenko (2004). "Algorithms for Estimating Information Distance with Application to Bioinformatics and Linguistics". arXiv:cs.CC/0404039.

- Jorma Rissanen (2007). Information and Complexity in Statistical Modeling. Springer S. p. 53. ISBN 978-0-387-68812-1.

- Ming Li; Paul M.B. Vitányi (2009). An Introduction to Kolmogorov Complexity and Its Applications. Springer. pp. 105–106. ISBN 978-0-387-49820-1.

- Ming Li; Paul M.B. Vitányi (2009). An Introduction to Kolmogorov Complexity and Its Applications. Springer. p. 119. ISBN 978-0-387-49820-1.

- Vitányi, Paul M.B. (2013). "Conditional Kolmogorov complexity and universal probability". Theoretical Computer Science. 501: 93–100. arXiv:1206.0983. doi:10.1016/j.tcs.2013.07.009.

Further reading

- Blum, M. (1967). "On the size of machines". Information and Control. 11 (3): 257. doi:10.1016/S0019-9958(67)90546-3.

- Brudno, A. (1983). "Entropy and the complexity of the trajectories of a dynamical system". Transactions of the Moscow Mathematical Society. 2: 127–151.

- Cover, Thomas M.; Thomas, Joy A. (2006). Elements of information theory (2nd ed.). Wiley-Interscience. ISBN 0-471-24195-4.

- Lajos, Rónyai; Gábor, Ivanyos; Réka, Szabó (1999). Algoritmusok. TypoTeX. ISBN 963-279-014-6.

- Li, Ming; Vitányi, Paul (1997). An Introduction to Kolmogorov Complexity and Its Applications. Springer. ISBN 978-0387339986.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Yu, Manin (1977). A Course in Mathematical Logic. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-0-7204-2844-5.

- Sipser, Michael (1997). Introduction to the Theory of Computation. PWS. ISBN 0-534-95097-3.

External links

- The Legacy of Andrei Nikolaevich Kolmogorov

- Chaitin's online publications

- Solomonoff's IDSIA page

- Generalizations of algorithmic information by J. Schmidhuber

- "Review of Li Vitányi 1997".

- Tromp, John. "John's Lambda Calculus and Combinatory Logic Playground". Tromp's lambda calculus computer model offers a concrete definition of K()]

- Universal AI based on Kolmogorov Complexity ISBN 3-540-22139-5 by M. Hutter: ISBN 3-540-22139-5

- David Dowe's Minimum Message Length (MML) and Occam's razor pages.

- Grunwald, P.; Pitt, M.A. (2005). Myung, I. J. (ed.). Advances in Minimum Description Length: Theory and Applications. MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-07262-9.