Kola Tembien

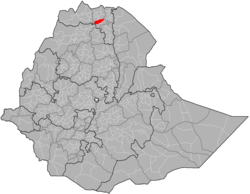

Kola Tembien (Tigrinya: ቆላ ተምቤን, "Lower Tembien") is one of the woredas in the Tigray Region of Ethiopia. It is named in part after the former province of Tembien. Part of the Mehakelegnaw Zone, Kola Tembien is bordered on the south by Abergele, on the west by the Tekezé River which separates it from the Semien Mi'irabawi (North Western) Zone, on the north by the Wari River which separates it from Naeder Adet and Werie Lehe, on the east by Misraqawi (Eastern) Zone, and on the southeast by Degua Tembien. Towns in Kola Tembien include Guya and Werkamba. The town of Abiy Addi is surrounded by Kola Tembien.

Kola Tembien ቆላ ተምቤን | |

|---|---|

| |

Flag | |

| |

| Region | Tigray |

| Zone | Mehakelegnaw (Central) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 2,538.39 km2 (980.08 sq mi) |

| Population (2007) | |

| • Total | 134,336 |

Demographics

The population pyramid has a wide base, not unlike most other low-income countries. However, the two lower age groups show that the pyramid base has stopped widening; this concerns particularly the group of 0–9 years old with an even more pronounced effect in the group of 0–4 years old, thus indicating a timid onset of a demographic transition. This may be related to the improved health services and a changing position of women in the society. Indeed, a revised Family Code came into effect in 2000, advocating the principles of gender equality. This raised the minimum age of marriage from 15 to 18 years old and established women rights in terms of sharing any assets the household has accumulated. The Ethiopian penal code states that it is a crime to beat one’s wife, and harmful traditional practices such as early marriage, abduction and female genital mutilation are now also considered to be a crime. Nowadays, almost all children are going to school but girls frequently drop out when they reach the age of 13 to 15 years: schools have no facilities for menstrual hygiene management and this is a major reason to interrupt schooling.[1]

Based on the 2007 national census conducted by the Central Statistical Agency of Ethiopia (CSA), this woreda has a total population of 134,336, an increase of 28.13% over the 1994 census, of whom 66,925 are men and 67,411 women; 0 or 0.00% are urban inhabitants. With an area of 2,538.39 square kilometers, Kola Tembien has a population density of 52.92, which is 56.29 than the Zone average of 0 persons per square kilometer. A total of greater households were counted in this woreda, resulting in an average of 8,871 persons to a household, and 28,917 housing units. The majority of the inhabitants said they practiced Ethiopian Orthodox Christianity, with 99.86% reporting that as their religion.[2]

The 1994 national census reported a total population for this woreda of 113,712, of whom 56,453 were men and 57,259 were women; 8,871 or 7.8% of its population were urban dwellers. The largest ethnic group reported in Kola Tembien was the Tigrayan (99.88%). Tigrinya was spoken as a first language by 99.82%. 98.23% of the population practiced Ethiopian Orthodox Christianity, and 1.69% were Muslim. Concerning education, 9.15% of the population were considered literate, which is less than the Zone average of 14.21%; 8.64% of children aged 7–12 were in primary school; 0.72% of the children aged 13–14 were in junior secondary school, and 0.86% of the inhabitants aged 15–18 were in senior secondary school. Concerning sanitary conditions, about 86% of the urban houses and 17% of all houses had access to safe drinking water at the time of the census; 11% of the urban and 3% of the total had toilet facilities.[3]

History of Kola Tembien

See: History of Tembien

Rock churches

Like several other districts in Tigray, Kola Tembien holds its share of rock-hewn or monolithic churches. These have literally been hewn from rock, mostly before the 10th C. CE.[4][5][6]

Notable landmarks in this woreda include the monastery of Abba Yohanni and the monolithic church of Gebriel Wukien, both of which are north of Abiy Addi.

Six rock-hewn churches are established along the slopes of the Degua Tembien massif.

The Mika’el Samba (13°42.56′N 39°6.81′E) rock church is completely rock hewn in Adigrat Sandstone. There are a series of grave cells leading off the main space. As this is not a village church, people come here only rarely, and it is locked most of the time. Priests are present particularly on Mika’els day, the twelfth day of every month in the Ethiopian calendar.[4]

The Maryam Hibeto rock church (13°42.67′N 39°6.44′E), located inconspicuously at the edge of the church forest and cemetery, is also completely hewn in Adigrat Sandstone, with an arched pronaos in front of it. The exterior of the colonnade column has a double capital. The ceiling is carved, and on either side are two elongated chambers which could have been the beginnings of an ambulatory, or else were living quarters. The main entrance to the church is at a lower level, down a number of steps and immediately on entering, a rectangular pool of water fed by a spring to the right. The floor is not level and the columns are stumpy with the springing coming halfway up the columns and oddly cut capitals.[4]

The Welegesa church (13°43′N 39°4′E) is hewn in Adigrat Sandstone. The entrance to the church buildings is in reality part of the rock forming two enclosures or courtyards, both hewn and open to the air. In the first courtyard there are a number of graves, and between the two, a block of stone with a cross in the window opening in the centre. The church proper, three-aisled, four bays in depth, is entered from either side through hewn passageways. The church ceiling is the same height throughout, with capitals, arches and cupolas to each bay, with a hewn tabot in the apse. The plan is sophisticated, with a central axis running north-south and the two open courtyards cut deep into the rock.[4]

The newly hewn Medhanie Alem rock church in Mt. Werqamba (13°42.86′N 39°00.27′E) is in a central, smaller peak (in Adigrat Sandstone).[7]

High in the mountains northwest of Abiy Addi, the Geramba rock church (13°38.84′N 39°1.55′E) is hewn in the top of a butte of Tertiary silicified limestone, under a thin cover of basalt. The columns are rather crudely carved, although slightly cruciform in plan and with bracket capitals much modified before the springing of the rough arches.[4]

Itsiwto Maryam rock church (13°40′N 39°1′E) is completely hewn in Adigrat Sandstone. The small church has an unusual continuous hipped ceiling to the centre aisle with carved diagonal crosses to the last section and a cross carved above the arch into the sanctuary. The ceiling is flat to the side aisles with longitudinal flat beams running lengthwise into the church, projecting and forming a continuous lintel – very similar to workmanship following the Tigrayan tradition. Access to the church is not permitted because of risk of collapse.[4]

Further up, in the Degua Tembien mountains at the east, there are an additional eight rock churches and natural caves with a church at its entrance.

Agriculture

A sample enumeration performed by the CSA in 2001 interviewed 27,665 farmers in this woreda, who held an average of 0.81 hectares of land. Of the 22,402 hectares of private land surveyed, 85.28% was in cultivation, 0.87% pasture, 10.78% fallow, 0.23% woodland, and 2.84% was devoted to other uses. For the land under cultivation in this woreda, 78.02% was planted in cereals, 4.61% in pulses, 1.82% in oilseeds, and 0.08% in vegetables. The area planted in gesho was 36 hectares; the amount of land planted in fruit trees is missing. 77.26% of the farmers both raised crops and livestock, while 19.75% only grew crops and 2.98% only raised livestock. Land tenure in this woreda is distributed amongst 89.01% owning their land, and 10.48% renting; the percentage reported as holding their land under other forms of tenure is missing.[8]

Geomorphology

Kola Tembien is one of the few places in the Ethiopian highlands where wind erosion occurs. Dunes are locally formed in places with wind shade.

Reservoirs

In this district with rains that last only for a couple of months per year, reservoirs of different sizes allow harvesting runoff from the rainy season for further use in the dry season. The reservoirs of the district include Addi Asme'e. Overall, these reservoirs suffer from rapid siltation.[9][10] Part of the water that could be used for irrigation is lost through seepage; the positive side-effect is that this contributes to groundwater recharge.[11]

Notes

- Nyssen, J.; De Rudder, F.; Vlassenroot, K.; Fredu Nega; Azadi, Hossein (2019). Socio-demographic profile, food insecurity and food-aid based response. In: Nyssen J., Jacob, M., Frankl, A. (Eds.). Geo-trekking in Ethiopia's Tropical Mountains - The Dogu'a Tembien District. SpringerNature. ISBN 978-3-030-04954-6.

- Census 2007 Tables: Tigray Region Archived 2010-11-14 at the Wayback Machine, Tables 2.1, 2.4, 2.5 and 3.4.

- 1994 Population and Housing Census of Ethiopia: Results for Southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples' Region, Vol. 1, part 1 Archived 2008-11-19 at the Wayback Machine, Tables 2.1, 2.12, 2.19, 3.5, 3.7, 6.3, 6.11, 6.13 (accessed 30 December 2008)

- Sauter, R. "Eglises rupestres du Tigré". Annales d'Ethiopie. 10: 157–175. doi:10.3406/ethio.1976.1168.

- Plant, R.; Buxton, D. (1970). "Rock-hewn churches of the Tigre province". Ethiopia Observer. 12 (3): 267.

- Gerster, G. (1972). Kirchen im Fels – Entdeckungen in Äthiopien. Zürich: Atlantis Verlag.

- Nyssen, J. (2019). Description of trekking routes in Dogu'a Tembien. In: Nyssen J., Jacob, M., Frankl, A. (Eds.). Geo-trekking in Ethiopia's Tropical Mountains - The Dogu'a Tembien District. SpringerNature. ISBN 978-3-030-04954-6.

- "Central Statistical Authority of Ethiopia. Agricultural Sample Survey (AgSE2001). Report on Area and Production - Tigray Region. Version 1.1 - December 2007" Archived 2009-11-14 at the Wayback Machine (accessed 26 January 2009)

- Vanmaercke, M. and colleagues (2019). "Sediment Yield and Reservoir Siltation in Tigray". Geo-trekking in Ethiopia's Tropical Mountains. GeoGuide. Cham (CH): Springer Nature. pp. 345–357. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-04955-3_23. ISBN 978-3-030-04954-6.

- Nigussie Haregeweyn, and colleagues (2006). "Reservoirs in Tigray: characteristics and sediment deposition problems". Land Degradation and Development. 17: 211–230. doi:10.1002/ldr.698.

- Nigussie Haregeweyn, and colleagues (2008). "Sediment yield variability in Northern Ethiopia: A quantitative analysis of its controlling factors". Catena. 75: 65–76. doi:10.1016/j.catena.2008.04.011.