Kivalina, Alaska

Kivalina (kiv-uh-LEE-nuh)[6] (Inupiaq: Kivalliñiq) is a city[7][8] and village in Northwest Arctic Borough, Alaska, United States. The population was 377 at the 2000 census[9] and 374 as of the 2010 census.[7]

Kivalina Kivalliñiq | |

|---|---|

City | |

Aerial view of Kivalina | |

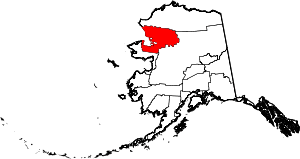

Location in Northwest Arctic Borough and the state of Alaska. | |

| Coordinates: 67°43′38″N 164°32′21″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Alaska |

| Borough | Northwest Arctic |

| Incorporated | June 23, 1969[1] |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Austin Swan, Sr.[2] |

| • State senator | Donny Olson (D) |

| • State rep. | John Lincoln (D) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 4.16 sq mi (10.78 km2) |

| • Land | 1.63 sq mi (4.23 km2) |

| • Water | 2.53 sq mi (6.55 km2) |

| Elevation | 13 ft (4 m) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 374 |

| • Estimate (2019)[5] | 379 |

| • Density | 232.37/sq mi (89.70/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-9 (Alaska (AKST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-8 (AKDT) |

| ZIP Code | 99750 |

| Area code | 907 |

| FIPS code | 02-39960 |

| GNIS feature ID | 1413348, 2419411 |

The island on which the village lies is threatened by rising sea levels and coastal erosion. As of 2013, it is predicted that the island will be inundated by 2025.[10]

History

Kivalina is an Inupiat community first reported as "Kivualinagmut" in 1847 by Lt. Lavrenty Zagoskin of the Imperial Russian Navy. It has long been a stopping place for travelers between Arctic coastal areas and Kotzebue Sound communities. Three bodies and artifacts were found in 2009 representing the Ipiutak culture, a pre-Thule, non-whaling civilization that disappeared over a millennium ago.[11]

It is the only village in the region where people hunt the bowhead whale. The original village was located at the north end of the Kivalina Lagoon but was relocated.

In about 1900, reindeer were brought to the area and some people were trained as reindeer herders.

An airstrip was built at Kivalina in 1960. Kivalina incorporated as a second-class city in 1969. During the 1970s, a new school and an electric system were constructed in the city.

On December 5, 2014 the only general store in Kivalina burned down.[12] In July 2015, a newer store was opened after months of rebuilding to make the store more convenient and safe.[13]

Geography

Kivalina is on the southern tip of a 12 km (7.5 mi) long barrier island located between the Chukchi Sea and a lagoon at the mouth of the Kivalina River.[14] It lies 130 km (81 mi) northwest of Kotzebue.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the village has a total area of 3.9 square miles (10 km2), of which, 1.9 square miles (4.9 km2) of it is land and 2.0 square miles (5.2 km2) of it (51.55%) is water.

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1920 | 87 | — | |

| 1930 | 99 | 13.8% | |

| 1940 | 98 | −1.0% | |

| 1950 | 117 | 19.4% | |

| 1960 | 142 | 21.4% | |

| 1970 | 188 | 32.4% | |

| 1980 | 241 | 28.2% | |

| 1990 | 317 | 31.5% | |

| 2000 | 377 | 18.9% | |

| 2010 | 374 | −0.8% | |

| Est. 2019 | 379 | [5] | 1.3% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[15] | |||

Kivalina first appeared on the 1920 U.S. Census as an unincorporated (native) village. It formally incorporated in 1969.

As of the census[9] of 2000, there were 377 people, 78 households, and 64 families residing in the village. The population density was 202.1 people per square mile (77.8/km2). There were 80 housing units at an average density of 42.9 per square mile (16.5/km2). The racial makeup of the village was 3.45% White and 96.55% Native American.

There were 78 households, out of which 61.5% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 62.8% were married couples living together, 15.4% had a female householder with no husband present, and 17.9% were non-families. 16.7% of all households were made up of individuals, and 3.8% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 4.83 and the average family size was 5.50. In the village the population was spread out, with 44.0% under the age of 18, 13.3% from 18 to 24, 20.7% from 25 to 44, 15.9% from 45 to 64, and 6.1% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 21 years. For every 100 females, there were 106.0 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 113.1 males.

The median income for a household in the village was $30,833, and the median income for a family was $30,179. Males had a median income of $31,875 versus $21,875 for females. The per capita income for the village was $8,360. About 25.4% of families and 26.4% of the population were below the poverty line, including 27.9% of those under age 18 and 30.0% of those age 65 or over.

Environmental issues

Due to severe sea wave erosion during storms, the city hopes to relocate again to a new site 12 km (7.5 mi) from the present site; studies of alternate sites are ongoing.[16] According to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the estimated cost of relocation runs between $95 and $125 million, whereas the Government Accountability Office (GAO) estimates it to be between $100 and $400 million.[17]

In 2011, Haymarket Books published "Kivalina: A Climate Change Story" by Christine Shearer.

Kivalina v. ExxonMobil Corporation

The city of Kivalina and a federally recognized tribe, the Alaska Native Village of Kivalina, sued Exxon Mobil Corporation, eight other oil companies, 14 power companies and one coal company in a lawsuit filed in federal court in San Francisco on February 26, 2008, claiming that the large amounts of greenhouse gases they emit contribute to global warming that threatens the community's existence.[18] The lawsuit estimated the cost of relocation at $400 million.[19] The suit was dismissed by the United States district court on September 30, 2009, on the grounds that regulating greenhouse emissions was a political rather than a legal issue and one that needed to be resolved by Congress and the Administration rather than by courts.[20]

Kivalina has also sued Canadian mining company Teck Cominco for polluting its water source.[21]

Orange goo

On August 4, 2011, it was reported that residents of the city of Kivalina had seen a strange orange goo wash up on the shores. According to the Associated Press, "Tests have been conducted on the substance on the surface of the water in Kivalina. City Administrator Janet Mitchell told the Associated Press that the substance has also shown up in some residents' rain buckets."[22] On August 8, 2011, Associated Press reported that the substance consisted of millions of microscopic eggs.[23] Later, officials of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) confirmed that the orange colored materials were some kind of crustacean eggs or embryos,[24][25][26] but subsequent examination resulted in a declaration that the substance consisted of spores from a possibly undescribed species of rust fungus,[27] later revealed to be Chrysomyxa ledicola.[28]

Kivalina in the Media

Kivalina's environmental issues were prominently featured in The 2015 Weather Channel documentary "Alaska: State of Emergency" hosted by Dave Malkoff. Kivalina was one of the two towns featured in the Al Jazeera English Fault Lines documentary, When the Water Took the Land.[29][30] The community, who were originally nomadic, were given an ultimatum that they would have to settle in the permanent community or their children would be taken from them.[31] The village's plight was also examined in Kivalina, an hourlong documentary released as part of the PBS World series America ReFramed.

Education

The McQueen School, operated by the Northwest Arctic Borough School District, serves the community. As of 2017 it had 141 students, with Alaska Natives making up 100% of the student body.[32]

See also

References

- 1996 Alaska Municipal Officials Directory. Juneau: Alaska Municipal League/Alaska Department of Community and Regional Affairs. January 1996. p. 81.

- 2015 Alaska Municipal Officials Directory. Juneau: Alaska Municipal League. 2015. p. 87.

- "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved June 30, 2020.

- "2010 City Population and Housing Occupancy Status". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved May 14, 2012.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- "Kivalina". Division of Community and Regional Affairs, Alaska Department of Commerce, Community and Economic Development. Archived from the original on December 30, 2012. Retrieved January 24, 2013.

- "Kivalina city, Alaska". Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010 Demographic Profile Data. United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved January 23, 2013.

- "Alaska Taxable 2011: Municipal Taxation - Rates and Policies" (PDF). Division of Community and Regional Affairs, Alaska Department of Commerce, Community and Economic Development. January 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-04-25.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- Stephen Sackur (30 July 2013). "The Alaskan village set to disappear underwater in a decade". BBC News.

- "Remains of ancient inhabitants found in Kivilina." Anchorage Daily News, 25 August 2009 Archived 27 August 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- DeMarban, Alex, "Fire Destroys General Store in Arctic Village of Kivalina", 5 December 2014. Alaska Dispatch News. Web. 11 Dec. 2014

- "This is climate change: Alaskan villagers struggle as island is chewed up by the sea" LA Times, 30 August 2015

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-06-18. Retrieved 2016-02-06.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)Environmental Assessment and Finding of No Significant Impact, Section 117 Expedited Erosion Control Project Kivilana Alaska, ACOE, September 2007, Retrieved 2010-06-20

- "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- An Alaska island is Losing Ground, Los Angeles Times, 25 Nov. 2007

- Abate, Randall S. (May 2010). "Public Nuisance Suits for the Climate Justice Movement: The Right Thing and the Right Time" (PDF). Washington Law Review. 85: 197–252.

- "Eskimo village sues over global warming", CNN, 26 February 2008.

- Felicity Barringer (2008-02-27). "Flooded Village Files Suit, Citing Corporate Link to Climate Change". New York Times. Retrieved 2008-02-29.

- Order Granting Motions to Dismiss, N.D. Cal., Sept. 30, 2009.

- "Teck Cominco to pay $120 million for Alaskan pipeline Archived March 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine", Montreal Gazette.

- "Mysterious orange goo washes up in Alaska village". Forbes. ANCHORAGE, Alaska. Retrieved 9 August 2011.

- Orange goo near remote Alaska village ID'd as eggs, Associated Press, August 8, 2011

- D'Oro, Rachel. "Orange goo near remote Alaska village ID'd as eggs". The Associated Press. Anchorage, Alaska: Google Search. Retrieved 9 August 2011.

- "Mysterious Orange Goo Baffles Remote Alaska Village". Fox News. August 6, 2011. Retrieved August 9, 2011.

- "Mystery Orange Goo in Remote Alaskan Village Identified". Fox News. August 8, 2011. Retrieved August 9, 2011.

- "Orange Goo on Alaska Shore Was Fungal Spores". Fox News. August 18, 2011. Retrieved August 18, 2011.

- "Alaska "Orange Goo" Rust Spores Confirmed". NCCOS News. National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science. 9 February 2012. Retrieved 7 March 2012.

An “orange goo” covered the Inupiat village of Kivalina, Alaska, last summer. Six months later the substance was confirmed by forestry experts at the USDA Forest Service and the Canadian Forest Service to be rust fungi uredospores of Chrysomyxa ledicola.

- "Alaska: When the Water Took the Land". Fault Lines. Al Jazeera English. 22 December 2015.

- Alaska News (18 December 2015). "Al Jazeera documentary tells tale of two eroding Alaska villages". Alaska Dispatch News.

- Arnold, Elizabeth (29 July 2008). "Tale Of Two Alaskan Villages". Day to Day. NPR.

- Home. McQueen School. Retrieved on March 26, 2017.

Further reading

- Arnold, Elizabeth (29 July 2008). "Tale Of Two Alaskan Villages". Day to Day. NPR.

- "Kivalina: The Canary in the Mine (5 min Snippet)". OneWorldTV. 23 April 2009.

- Sackur, Stephen (30 July 2013). "The Alaskan village set to disappear under water in a decade". BBC News.

- "Alaska: When the Water Took the Land". Fault Lines. Al Jazeera English. 22 December 2015.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kivalina, Alaska. |

- Re-Locate Kivalina

- Alaska Climate Change Impact Mitigation Program: Kivalina at Department of Commerce, Community, and Economic Development, State of Alaska