Kisimul Castle

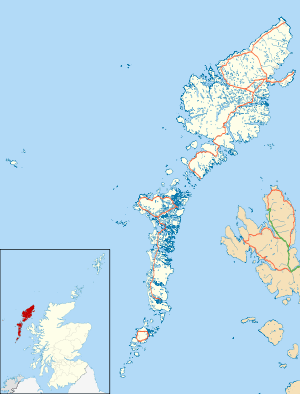

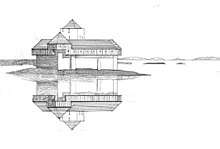

Kisimul Castle (Scottish Gaelic: Caisteal Chiosmuil)[1] and also known as Kiessimul Castle,[2] is a medieval castle located on a small island off Castlebay, Barra, in the Outer Hebrides, Scotland. It gets its name from the Gaelic ciosamul meaning "castle island".[3]

| Kisimul Castle | |

|---|---|

| Part of Barra, Western Isles | |

| Castlebay, Scotland | |

.jpg) The castle as seen from the air, with Castlebay town in the background. | |

Kisimul Castle | |

| Coordinates | 56°57′08″N 7°29′15″W |

| Type | Rectangular castle |

| Height | 11 metres (36 ft) |

| Site information | |

| Owner | Clan MacNeil |

| Controlled by | Historic Scotland |

| Open to the public | Yes |

| Condition | Partially restored |

| Site history | |

| In use | Until 1838 |

| Materials | Granite |

History

The earliest documentary record of Kisimul Castle dates from the mid 16th century.[4] Writing in 1549, Dean Monro stated of Barra that "Within the southwest end of this isle, ther enters a salt water loche, verey narrow in the entrey, and round and braide within. Into the middis of the saide loche there is ane ile, upon ane strenthey craige, callit Kiselnin, perteining to M’Kneil of Barray."[5] However, Campbell (1936) points out that Monro has in part confused the nearby Bàgh Beag with Bàgh a' Chaisteil.[6]

The castle is built on a rocky islet in the bay, just off the coast of Barra. It can only be reached by boat. Kisimul has its own fresh water wells. Legend has it that was the stronghold of the MacNeils since the 11th century.

Kisimul was abandoned in 1838 when the island was sold, and the castle's condition subsequently deteriorated. Some of its stone was used as ballast for fishing vessels, and some even ended up as paving in Glasgow. The remains of the castle, along with most of the island of Barra, were purchased in 1937 by Robert Lister MacNeil, the then chief of Clan MacNeil, who made efforts at restoration.

In 2001 the castle was leased by the chief of Clan MacNeil to Historic Scotland for 1000 years for the annual sum of £1 and a bottle of whisky.[7] For the 2011 census the island was classified by the National Records of Scotland as an inhabited island that "had no usual residents at the time of either the 2001 or 2011 censuses".[1][Note 1]

Archaeological survey

Archaeological investigations were carried out at Kisimul Castle by Headland Archaeology, on behalf of Historic Scotland.[8] This involved some excavation, building recording and archival research. It was hoped that the project would help clarify the date of the castle and its sequence of construction. Another aim was to establish whether or not the island had been occupied before construction of the castle.

The dating of the castle was particularly difficult due to the lack of datable architectural features visible in the castle fabric. The results of the building recording and archival research concluded a likely date of construction during the late 15th century coinciding with the height of Gaelic power in Scotland and Ireland during the Middle Ages. Records make no mention of it during the reign of Robert II (1371-90), in the island descriptions in the Chronica Gentis Scotorum (1371-1387) or in the initial grant of the island of Barra to the MacNeills from 1427. This ‘negative’ evidence supports the hypothesis that Kisimul postdates these records since it presumably would have been mentioned if it existed during those times.

It is possible that timber hoardings were a part of the original castle design, due to the presence of putlog holes in the curtain wall. However the holes are not level with the wall walk as would be expected of this particular building feature. As this trend was going out of fashion at the time when Kisimul was built it is thought that they had a more decorative, than defensive function, such as providing extra space for people to walk and exercise in a castle where its location meant that space for such activities was limited. [10]

Excavation concentrated on areas of the courtyard, the basement of the tower and the bottom of a pit prison. At the east end of the courtyard there was a great deal of building rubble directly below the surface, some of which had mortar attached. This suggested that an earlier building had been demolished or collapsed, and the stone used to form a level courtyard. This happened before the building known as the kitchen was built. At the other end of the site a stone drain leading under the great hall was uncovered together with a paved stone surface. Above these was a layer containing large amounts of animal bone, shell and pottery. There were also floor surfaces within buildings that had been demolished.

During the excavation many finds were recovered. These included large quantities of animal bone and shell. Further study of these will allow us to discover more about the diet of those who lived in the castle. A large quantity of broken pottery was also found and appears to range in date from prehistoric times through the medieval period to the more recent past. A number of pieces of flint were recovered including a particularly fine flint blade. These tools together with some of the pottery show that people were using the island thousands of years before the present castle was built.

Images

.jpg)

.jpg)

Kisimul Castle from Barra (1997)

Kisimul Castle from Barra (1997)

View of Castlebay from Heaval

View of Castlebay from Heaval Kisimul Castle - View from the battlements

Kisimul Castle - View from the battlements Floor plan of Kisimul Castle, Scotland, United Kingdom. 1 Keep 2 Kitchen 3 Tanist House 4 Postern 5 Marion of the Head's Addition 6 Great Hall 7 Watchtower 8 Chapel 9 Gockman's House 10 Courtyard 11 Gate 12 Slipway 13 Creek 14 Breakwater wall 15 Crew's house

Floor plan of Kisimul Castle, Scotland, United Kingdom. 1 Keep 2 Kitchen 3 Tanist House 4 Postern 5 Marion of the Head's Addition 6 Great Hall 7 Watchtower 8 Chapel 9 Gockman's House 10 Courtyard 11 Gate 12 Slipway 13 Creek 14 Breakwater wall 15 Crew's house

See also

Notes

- There were 93 inhabited islands listed in the 2011 census and more than 20 others that are inhabited from time to time but are not so listed.[1]

References

- National Records of Scotland (15 August 2013). "Appendix 2: Population and households on Scotland's Inhabited Islands" (PDF). Statistical Bulletin: 2011 Census: First Results on Population and Household Estimates for Scotland Release 1C (Part Two) (PDF) (Report). SG/2013/126. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- "Barra, Kiessimul Castle". CANMORE. Retrieved 23 August 2013.

- Mac an Tàilleir, Iain (2003) Ainmean-àite/Placenames. (pdf) Pàrlamaid na h-Alba. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- McDonald, R. Andrew (1997). The Kingdom of the Isles: Scotland's Western Seaboard c.1100-c.1336. East Linton, East Lothian, Scotland: Tuckwell Press. pp. 236–237. ISBN 1-898410-85-2.

- Monro, Sir Donald (1549) Description of the Western Isles of Scotland. William Auld. Edinburgh - 1774 edition.

- Campbell, John Lorne ed) (1936) The Book of Barra. Acair - reprinted 2006.

- "Islands gifted to residents". BBC News. 2003-09-05. Retrieved 2010-05-07.

- "Site Record for Barra, Kiessimul Castle Kisimul Castle; Caisteal Chiosmuil; Castlebay; Kiessamul Castle; Castle Bay; Bagh A' ChaisteilDetails Details". Rcahms.gov.uk. Retrieved 2012-10-23.

- Holden, Timothy (2016). "Kisimul, Isle of Barra. Part 1: The Castle and the MacNeills". Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. 146: 208.

- Holden, Timothy (2016). "Kisimul, Isle of Barra. Part 1: The Castle and the MacNeills". Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. 146: 181–213.