Kimura's disease

Kimura's disease is a benign rare chronic inflammatory disorder. Its primary symptoms are subdermal lesions in the head or neck or painless unilateral inflammation of cervical lymph nodes.[1]

| Kimura disease | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Eosinophilic lymphogranuloma, angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia, eosinophilic granuloma of soft tissue, eosinophilic lymphofollicular granuloma |

| |

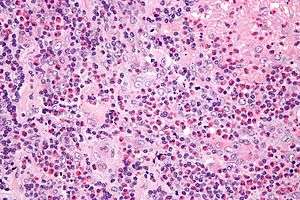

| Micrograph of Kimura disease, H&E stain | |

| Specialty | Oncology |

Cause

Its cause remains unknown. Reasons such as an allergic reaction, tetanus toxoid vaccination,[2][3][4] or an alteration of immune regulation are suspected. Other theories like persistent antigenic stimulation following arthropod bites and parasitic or candidal infection have also been proposed. To date, none of these theories has been substantiated.[1]

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of Kimura's disease remains unknown, although an allergic reaction, trauma, and an autoimmune process have all been implicated as possible causes. The disease is manifested by an abnormal proliferation of lymphoid follicles and vascular endothelium. Peripheral eosinophilia and the presence of eosinophils in the inflammatory infiltrate suggest it may be a hypersensitivity reaction. Some evidence has indicated TH2 lymphocytes may also play a role, but further investigation is needed.

Kimura's disease is generally limited to the skin, lymph nodes, and salivary glands, but patients with Kimura's disease and nephrotic syndrome have been reported. The basis of this possible association is unclear.[1]

Diagnosis

An open biopsy is the chief means by which this disease is diagnosed.

"Lymphoid nodules with discrete germinal centers can occupy an area extending from the reticular dermis to the fascia and muscle. Follicular hyperplasia, marked eosinophilic infiltrate and eosinophilic abscesses, and the proliferation of postcapillary venules are characteristic histological findings. [18] Centrally, thick-walled vessels are present with hobnail endothelial cells. Immunohistochemical evaluation of the lymphoid nodules demonstrates a polymorphous infiltrate without clonality. [12, 27] Reports have also demonstrated the presence of plasmacytoid dendritic cells in a lesion of Kimura disease. [40] Histopathological examination is an effective way to establish the diagnosis."[5]

Treatment

Observation is acceptable if the lesions are neither symptomatic nor disfiguring. Intralesional or oral steroids can shrink the nodules, but seldom result in cure.

Cyclosporine has been reported to induce remission in patients with Kimura's disease, but recurrence of the lesions has been observed once this therapy is stopped.

Cetirizine is an effective agent in treating its symptoms. Cetirizine's properties of being effective both in the treatment of pruritus (itching) and as an anti-inflammatory agent make it suitable for the treatment of the pruritus associated with these lesions.[6] In a 2005 study, the American College of Rheumatology conducted treatments initially using prednisone, followed by steroid dosages and azathioprine, omeprazole, and calcium and vitamin D supplements over the course of two years.[6] The skin condition of the patient began to improve and the skin lesions lessened. However, symptoms of cushingoid and hirsutism were observed before the patient was removed from the courses of steroids and placed on 10 mg/day of cetirizine to prevent skin lesions;[6] an agent suitable for the treatment of pruritus associated with such lesions.[6] Asymptomatically, the patient's skin lesions disappeared after treatment with cetirizine, blood eosinophil counts became normal,[6] corticosteroid effects were resolved,[6] and a remission began within a period of two months.[6] The inhibition of eosinophils may be the key to treatment of Kimura's disease due to the role of eosinophils, rather than other cells with regards to the lesions of the skin.[6]

Radiotherapy has been used to treat recurrent or persistent lesions. However, considering the benign nature of this disease, radiation should be considered only in cases of recurrent, disfiguring lesions.

Surgery has been considered the mainstay of therapy. However, recurrence after surgery is common.[7]

In 2011, an eight-year-old boy had presented with a firm, nontender, nonfluctuating 15- to 12-cm mass on the left side of the neck involving the lateral region of the neck and jaw and a 5- to 7-cm mass on the right side of his neck. He had an eosinophil concentration of 36% (absolute count: 8172/ml), his IgE level was 9187 IU/ml. He was diagnosed with Kimura's disease. Initially treated with corticosteroids, he was given a single dose of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) as a steroid-sparing agent after the disease flared while tapering prednisone. After IVIG administration, improvement was rapid, both left and right cervical masses diminished to less than 1 cm and his eosinophil and IgE levels returned to normal range. He has been free of disease during a six-year follow-up. IVIG may have value in the treatment of Kimura's disease.[8]

A study is going on to assess the efficacy of tacrolimus on Kimura's disease. One case has so far been described. A patient with refractory Kimura's disease after surgery and treatment with prednisone was treated with tacrolimus. Tacrolimus (FK-506) was administered at an initial dosage of 1 mg every 12 hours, and FK-506 concentration in the blood was monitored monthly. FK-506 blood concentration was controlled within 5 to 15 μg/l. After 6 months, the dosage of tacrolimus was reduced to 0.5 mg daily for another 2 months and then treatment was stopped. Swelling of the bilateral salivary glands disappeared within the first week. No serious side effects were noted and the disease has not recurred in the 2 years of follow-up. Tacrolimus may be an effective treatment for patients with Kimura's disease, but more research is needed to determine its long-term efficacy and safety, as well as its mechanism of action.[9]

Frequency

Kimura's disease is said to be predominantly seen in males of Asian descent.[1] However, a study of 21 cases in the United States showed no racial preference, of 18 males and three females (male/female ratio 6:1), 8 to 64 years of age (mean, 32 years), and seven Caucasians, six Blacks, six Asians, one Hispanic, and an Arab were included.[10]

Assessing the prevalence is difficult. The medical literature alone holds over 500 case reports and series (typically two, three cases) from the 1980s to early 2017 in English, excluding the existing Chinese, Japanese, and Korean medical reports that add more cases.

History

The first known report of Kimura's disease was from China in 1937, when Kimm and Szeto identified seven cases of the condition.[11] It first received its name in 1948 when Kimura and others noted a change in the surrounding blood vessels and referred to it as "unusual granulation combined with hyperplastic changes in lymphoid tissue."[12]

See also

- Kikuchi's disease

- List of cutaneous conditions

References

- Lee S (May 2007). "Kimura Disease". eMedicine. Retrieved 2008-07-20.

- Jeon EK, Cho AY, Kim MY, Lee Y, Seo YJ, Park JK, Lee JH (February 2009). "Angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia that was possibly induced by vaccination in a child". Annals of Dermatology. 21 (1): 71–4. doi:10.5021/ad.2009.21.1.71. PMC 2883376. PMID 20548862.

- Akosa AB, Ali MH, Khoo CT, Evans DM (June 1990). "Angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia associated with tetanus toxoid vaccination". Histopathology. 16 (6): 589–93. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2559.1990.tb01164.x. PMID 2376400.

- Hallam LA, Mackinlay GA, Wright AM (September 1989). "Angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia: possible aetiological role for immunisation". Journal of Clinical Pathology. 42 (9): 944–9. doi:10.1136/jcp.42.9.944. PMC 501794. PMID 2794083.

- Snyder, Alan. "Kimura Disease". emedicine.medscape.com. Medscape. Retrieved 16 October 2018.

- Ben-Chetrit E, Amir G, Shalit M (February 2005). "Cetirizine: An effective agent in Kimura's disease". Arthritis and Rheumatism. 53 (1): 117–8. doi:10.1002/art.20908. PMID 15696573.

- "Kimura Disease Treatment & Management". medscape.

- Hernandez-Bautista V, Yamazaki-Nakashimada MA, Vazquez-García R, Stamatelos-Albarrán D, Carrasco-Daza D, Rodríguez-Lozano AL (December 2011). "Treatment of Kimura disease with intravenous immunoglobulin". Pediatrics. 128 (6): e1633-5. doi:10.1542/peds.2010-1623. PMID 22106083.

- Da-Long S, Wei R, Bing G, Yun-Yan Z, Xiang-Zhen L, Xin L (February 2014). "Tacrolimus on Kimura's disease: a case report". Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology and Oral Radiology. 117 (2): e74-8. doi:10.1016/j.oooo.2012.04.022. PMID 22939325.

- Chen H, Thompson LD, Aguilera NS, Abbondanzo SL (April 2004). "Kimura disease: a clinicopathologic study of 21 cases". The American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 28 (4): 505–13. doi:10.1097/00000478-200404000-00010. PMID 15087670.

- Kimm HT, Szeto C (1937). "Eosinophilic hyperplastic lymphogranuloma, comparison with Mikulicz's disease". Proc Chin Med Soc: 329.

- Kimura T, Yoshimura S, Ishikawa E (1948). "On the unusual granulation combined with hyperplastic changes of lymphatic tissues". Trans Soc Pathol Jpn: 179–180.

External links

| Classification |

|

|---|---|

| External resources |