Cimon

Cimon (/ˈsaɪmən/; c. 510 – 450 BC) or Kimon (/ˈkaɪmən/;[1] Greek: Κίμων, Kimōn)[2] was an Athenian statesman and general in mid-5th century BC Greece. He was the son of Miltiades, the victor of the Battle of Marathon. Cimon played a key role in creating the powerful Athenian maritime empire following the failure of the Persian invasion of Greece by Xerxes I in 480–479 BC. Cimon became a celebrated military hero and was elected to the rank of strategos after fighting in the Battle of Salamis.

Cimon | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | c. 510 Athens |

| Died | 450 BC Citium, Cyprus |

| Allegiance | Athens |

| Rank | Strategos (general) |

| Battles/wars | Battle of Salamis Battle of Salamis (in Cyprus) |

One of Cimon's greatest exploits was his destruction of a Persian fleet and army at the Battle of the Eurymedon river in 466 BC. In 462 BC, he led an unsuccessful expedition to support the Spartans during the helot uprisings. As a result, he was dismissed and ostracized from Athens in 461 BC; however, he was recalled from his exile before the end of his ten-year ostracism to broker a five-year peace treaty in 451 BC between Sparta and Athens. For this participation in pro-Spartan policy, he has often been called a laconist. Cimon also led the Athenian aristocratic party against Pericles and opposed the democratic revolution of Ephialtes seeking to retain aristocratic party control over Athenian institutions.

Life

Early years

Cimon was born into Athenian nobility in 510 BC. He was a member of the Philaidae clan, from the deme of Laciadae (Lakiadai). His grandfather was Cimon the Silly, who won three Olympic victories with his four-horse chariot and was assassinated by the sons of Peisistratus.[2] His father was the celebrated Athenian general Miltiades[3] and his mother was Hegesipyle, daughter of the Thracian king Olorus and a relative of the historian Thucydides.[4]

While Cimon was a young man, his father was fined 50 talents after an accusation of treason by the Athenian state. As Miltiades could not afford to pay this amount, he was put in jail, where he died in 489 BC. Cimon inherited this debt and, according to Diodorus, some of his father's unserved prison sentence[3] in order to obtain his body for burial.[5] As the head of his household, he also had to look after his sister or half-sister Elpinice. According to Plutarch, the wealthy Callias took advantage of this situation by proposing to pay Cimon's debts for Elpinice's hand in marriage. Cimon agreed.[6][7][8]

Cimon in his youth had a reputation of being dissolute, a hard drinker, and blunt and unrefined; it was remarked that in this latter characteristic he was more like a Spartan than an Athenian.[9][10]

Marriage

Cimon is repeatedly said to have married or been otherwise involved with his sister or half-sister Elpinice (who herself had a reputation for sexual immorality) prior to her marriage with Callias, although this may be a legacy of simple political slander.[9][5] He later married Isodice, Megacles' granddaughter and a member of the Alcmaeonidae family. Their first children were twin boys named Lacedaemonius (who would become an Athenian commander) and Eleus. Their third son was Thessalus (who would become a politician).

Military career

During the Battle of Salamis, Cimon distinguished himself by his bravery. He is mentioned as being a member of an embassy sent to Sparta in 479 BC.

Between 478 BC and 476 BC, a number of Greek maritime cities around the Aegean Sea did not wish to submit to Persian control again and offered their allegiance to Athens through Aristides at Delos. There, they formed the Delian League (also known as the Confederacy of Delos), and it was agreed that Cimon would be their principal commander.[11] As strategos, Cimon commanded most of the League's operations until 463 BC. During this period, he and Aristides drove the Spartans under Pausanias out of Byzantium.

Cimon also captured Eion on the Strymon[2] from the Persian general Boges. Other coastal cities of the area surrendered to him after Eion, with the notable exception of Doriscus. He also conquered Scyros and drove out the pirates who were based there.[6][12] On his return, he brought the "bones" of the mythological Theseus back to Athens. To celebrate this achievement, three Herma statues were erected around Athens.[6]

Battle of the Eurymedon

Around 466 BC, Cimon carried the war against Persia into Asia Minor and decisively defeated the Persians at the Battle of the Eurymedon on the Eurymedon River in Pamphylia. Cimon's land and sea forces captured the Persian camp and destroyed or captured the entire Persian fleet of 200 triremes manned by Phoenicians. And he established an Athenian colony nearby called Amphipolis with 10,000 settlers.[11] Many new allies of Athens were then recruited into the Delian League, such as the trading city of Phaselis on the Lycian-Pamphylian border.

There is a view amongst some historians that while in Asia Minor, Cimon negotiated a peace between the League and the Persians after his victory at the Battle of the Eurymedon. This may help to explain why the Peace of Callias negotiated by his brother-in-law in 450 BC is sometimes called the Peace of Cimon as Callias' efforts may have led to a renewal of Cimon's earlier treaty. He had served Athens well during the Persian Wars and according to Plutarch: "In all the qualities that war demands he was fully the equal of Themistocles and his own father Miltiades".[6][11]

Thracian Chersonesus

After his successes in Asia Minor, Cimon moved to the Thracian colony Chersonesus. There he subdued the local tribes and ended the revolt of the Thasians between 465 BC and 463 BC. Thasos had revolted from the Delian League over a trade rivalry with the Thracian hinterland and, in particular, over the ownership of a gold mine. Athens under Cimon laid siege to Thasos after the Athenian fleet defeated the Thasos fleet. These actions earned him the enmity of Stesimbrotus of Thasos (a source used by Plutarch in his writings about this period in Greek history).

Trial for bribery

Despite these successes, Cimon was prosecuted by Pericles for allegedly accepting bribes from Alexander I of Macedon. During the trial, Cimon said: "Never have I been an Athenian envoy, to any rich kingdom. Instead, I was proud, attending to the Spartans, whose frugal culture I have always imitated. This proves that I don't desire personal wealth. Rather, I love enriching our nation, with the booty of our victories." As a result, Elpinice convinced Pericles not to be too harsh in his criticism of her brother. Cimon was in the end acquitted.[6]

Helot revolt in Sparta

Cimon was Sparta's Proxenos at Athens, he strongly advocated a policy of cooperation between the two states. He was known to be so fond of Sparta that he named one of his sons Lacedaemonius.[13][14] In 462 BC, Cimon sought the support of Athens' citizens to provide help to Sparta. Although Ephialtes maintained that Sparta was Athens' rival for power and should be left to fend for itself, Cimon's view prevailed. Cimon then led 4,000 hoplites to Mt. Ithome to help the Spartan aristocracy deal with a major revolt by its helots. However, this expedition ended in humiliation for Cimon and for Athens when, fearing that the Athenians would end up siding with the helots, Sparta sent the force back to Attica.[15]

Exile

This insulting rebuff caused the collapse of Cimon's popularity in Athens. As a result, he was ostracised from Athens for ten years beginning in 461 BC [16]. The reformer Ephialtes then took the lead in running Athens and, with the support of Pericles, reduced the power of the Athenian Council of the Areopagus (filled with ex-archons and so a stronghold of oligarchy).

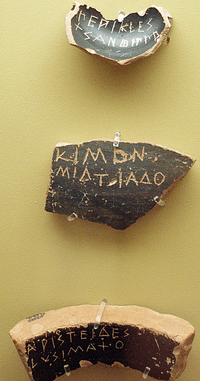

Power was transferred to the citizens, i.e. the Council of Five Hundred, the Assembly, and the popular law courts. Some of Cimon's policies were reversed including his pro-Spartan policy and his attempts at peace with Persia. Many ostraka bearing his name survive; one bearing the spiteful inscription: "Cimon, son of Miltiades, and Elpinice too" (his haughty sister).

In 458 BC, Cimon sought to return to Athens to assist its fight against Sparta at Tanagra, but was rebuffed.

Return

Eventually, around 451 BC, Cimon returned to Athens. Although he was not allowed to return to the level of power he once enjoyed, he was able to negotiate on Athens' behalf a five-year truce with the Spartans. Later, with a Persian fleet moving against a rebellious Cyprus, Cimon proposed an expedition to fight the Persians. He gained Pericles' support and sailed to Cyprus with two hundred triremes of the Delian League. From there, he sent sixty ships under Admiral Charitimides to Egypt to help the Egyptian revolt of Inaros, in the Nile Delta. Cimon used the remaining ships to aid the uprising of the Cypriot Greek city-states.

Rebuilding Athens

From his many military exploits and money gained through the Delian League, Cimon funded many construction projects throughout Athens. These projects were greatly needed in order to rebuild after the Achaemenid destruction of Athens. He ordered the expansion of the Acropolis and the walls around Athens, and the construction of public roads, public gardens, and many political buildings.[17]

Death on Cyprus

Cimon laid siege to the Phoenician and Persian stronghold of Citium on the southwest coast of Cyprus in 449 BC; he died during or soon after the failed attempt.[3] However, his death was kept secret from the Athenian army, who subsequently won an important victory over the Persians under his 'command' at Salamis-in-Cyprus.[18] He was later buried in Athens,[19] where a monument was erected in his memory.

Historical Significance

During his period of considerable popularity and influence at Athens, Cimon's domestic policy was consistently antidemocratic, and this policy ultimately failed. His success and lasting influence came from his military accomplishments and his foreign policy, the latter being based on two principles: continued resistance to Persian aggression, and recognition that Athens should be the dominant sea power in Greece, and Sparta the dominant land power. The first principle helped to ensure that direct Persian military aggression against Greece had essentially ended; the latter probably significantly delayed the outbreak of the Peloponnesian War.[10]

See also

- Amphictyonic League

- Long Walls

- Battle of Salamis in Cyprus (450 BC)

Notes

- EA (1920).

- DGRB&M (1867), p. 749.

- EB (1878).

- EB (1911), p. 368.

- DGRB&M (1867), p. 750.

- Plutarch, Lives. Life of Cimon.(University of Calgary/Wikisource)

- Cornelius Nepos, Lives of Eminent Commanders

- Plutarch, Lives. Life of Themistocles. (University of Massachusetts/Wikisource)

- Plutarch, Cimon 481.

- Bury, J. B.; Meiggs, Russell (1956). A history of Greece to the death of Alexander the Great, 3rd edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 343.

- Thucydides, The History of the Peloponnesian War.

- Herodotus, The History of Herodotus.

- The History of the Peloponnesian War by Thucydides, Donald Lateiner, Richard Crawley page 33 ISBN 0-486-43762-0

- Who's who in the Greek world By John Hazel Page 56 ISBN 0-415-12497-2

- The Greek World: 479–323 BC, Simon Hornblower. Page 126.

- Goušchin, Valerij (2019-02-26). "Plutarch on Cimon, Athenian Expeditions, and Ephialtes' Reform (Plut. Cim. 14-17)". Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies. 59 (1): 38–56. ISSN 2159-3159.

- Wycherley, R.E. (1992). "Rebuilding in Athens and Attica". Cambridge Histories. 5: 206–222.

- Plutarch, Cimon, 19

- EB (1911), p. 369.

References

- Mitchell, John Malcolm (1911), , in Chisholm, Hugh (ed.), Encyclopædia Britannica, 6 (11th ed.), Cambridge University Press, pp. 368–9

- Nepos, Cornelius, "Cimon", On Illustrious Men (in Latin)

- Plutarch, "Life of Cimon", Lives of the Noble Greeks and Romans (in Ancient Greek)

- Rines, George Edwin, ed. (1920), , Encyclopedia Americana, 6 VI

- Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War (in Ancient Greek)

- Matteo Zaccarini, The Lame Hegemony. Cimon of Athens and the Failure of Panhellenism ca. 478-450 BC, Bologna, Bononia University Press, 2017

External links

- Cimon of Athens, in About.com.