Kilte Awulaelo

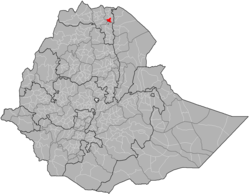

Kilte Awulaelo (Tigrinya: ክልተ ኣውላዕሎ) is one of the woredas in the Tigray Region of Ethiopia. Part of the Misraqawi Zone, Kilte Awulaelo is bordered on the south by the Debub Misraqawi (Southeastern) Zone, on the west by the Mehakelegnaw (Central) Zone, on the northeast by Hawzen, on the north by Saesi Tsaedaemba, and on the east by Atsbi Wenberta. Towns in the Kilte Awulaelo woreda include Agula, Tsigereda and Maymagden. Town of Wukro is surrounded by Kilte Awulaelo.

Kilte Awulaelo ክልተ ኣውላዕሎ | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

Flag | |

| |

| Region | Tigray |

| Zone | Misraqawi (Eastern) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 2,068.25 km2 (798.56 sq mi) |

| Population (2007) | |

| • Total | 99,708 |

Overview

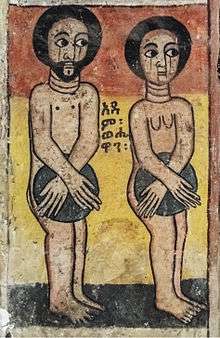

Archeological surveys at the village of Aynalem has recovered Sabaean inscriptions, an obelisk carved from stone, rocks shaped to resemble Egyptian pyramids, and ancient metal utensils in an area which has been left uncultivated due to religious beliefs. Gezaei Haile, a scientist and geology instructor at Mekelle University, in an interview with Jimma Times dated these artifacts to "a time of 200 years before birth of Christ, as none of the antiquities have sign of cross on them."[1] There are several local monolithic churches in this woreda. These include Wukro Chirkos (at the edge of Wukro town), Abreha we Atsbeha, and Minda'e Mikael.[2] The village of Negash, widely believed to be the first Muslim settlement in Africa, is also an important local landmark.

Wukro was one of nine woredas in Tigray most affected by a drought during 2008, requiring emergency food supplies to be requested for an estimated 600,000 people.[3]

Demographics

The population pyramid has a wide base, not unlike most other low-income countries. However, the two lower age groups show that the pyramid base has stopped widening; this concerns particularly the group of 0–9 years old with an even more pronounced effect in the group of 0–4 years old, thus indicating a timid onset of a demographic transition. This may be related to the improved health services and a changing position of women in the society. Indeed, a revised Family Code came into effect in 2000, advocating the principles of gender equality. This raised the minimum age of marriage from 15 to 18 years old and established women rights in terms of sharing any assets the household has accumulated. The Ethiopian penal code states that it is a crime to beat one’s wife, and harmful traditional practices such as early marriage, abduction and female genital mutilation are now also considered to be a crime. Nowadays, almost all children are going to school but girls frequently drop out when they reach the age of 13 to 15 years: schools have no facilities for menstrual hygiene management and this is a major reason to interrupt schooling.[4]

Based on the 2007 national census conducted by the Central Statistical Agency of Ethiopia (CSA), this woreda has a total population of 99,708, an increase of 16.53% over the 1994 census, of whom 48,645 are men and 51,063 women; 4,808 or 4.82% are urban inhabitants. With an area of 2,068.25 square kilometers, Wukro has a population density of 48.21, which is less than the Zone average of 56.93 persons per square kilometer. A total of 21,657 households were counted in this woreda, resulting in an average of 4.60 persons to a household, and 20,932 housing units. The majority of the inhabitants said they practiced Ethiopian Orthodox Christianity, with 97.08% reporting that as their religion, while 2.8% of the population were Muslim.[5]

The 1994 national census reported a total population for this woreda of 85,561, of whom 41,404 were men and 44,157 were women; 19,894 or 23.25% of its population were urban dwellers. The two largest ethnic groups reported in Wukro were the Tigrayan (98.55%), and the Afar (1.16%); all other ethnic groups made up 0.29% of the population. Tigrinya is spoken as a first language by 99.83%. The majority of the inhabitants practiced Ethiopian Orthodox Christianity, with 95.2% reporting that as their religion, while 4.69% were Muslim. Concerning education, 18.08% of the population were considered literate, which is greater than the Zone average of 9.01%; 28.78% of children aged 7–12 were in primary school; 1.85% of the children aged 13–14 were in junior secondary school; 4.65% of the inhabitants aged 15–18 were in senior secondary school. Concerning sanitary conditions, about 90% of the urban houses and 37% of all houses had access to safe drinking water at the time of the census; about 40% of the urban and about 17% of the total had toilet facilities.[6]

_harde_zandsteen_(rotswand)_over_tilliet_(onderste_deel_van_de_helling)_en_afstorting.jpg)

Agriculture

A sample enumeration performed by the CSA in 2001 interviewed 15,542 farmers in this woreda, who held an average of 0.94 hectares of land. Of the 14,563 hectares of private land surveyed, 86.4% was under cultivation, 2.38% pasture, 7.2% fallow, 0.63% in woodland, and 3.38% was devoted to other uses. For the land under cultivation in this woreda, 73% was planted in cereals, 8.2% in pulses, 2% in oilseeds, and 9 hectares in vegetables. The total area planted in fruit trees was 408 hectares, while 4 hectare was planted in gesho. 74.83% of the farmers both raised crops and livestock, while 20.18% only grew crops and 4.99% only raised livestock. Land tenure in this woreda is distributed amongst 84.22% owning their land, 14.35% renting, and 1.43% holding their land under other forms of tenure.[7]

Rivers

The two main rivers of this woreda are Genfel and Agula'i River, which both drain to Giba River.

Reservoirs

In this district with rains that last only for a couple of months per year, reservoirs of different sizes allow harvesting runoff from the rainy season for further use in the dry season. The Lake Giba is under construction at the southwestern edge of the woreda. Smaller reservoirs include Gereb May Zib'i and Ginda'i. Overall, these reservoirs suffer from rapid siltation.[8][9] Part of the water that could be used for irrigation is lost through seepage; the positive side-effect is that this contributes to groundwater recharge.[10]

Surrounding woredas

Notes

- "Group of Ethiopian Scientists Discover Ancient Antiquities" Archived 2008-06-03 at the Wayback Machine, Jimma times website, originally published 30 November 2007 (accessed 14 December 2009)

- Described in Philip Briggs, Ethiopia: The Bradt Travel Guide, 3rd edition (Chalfont St Peters: Bradt, 2002), p. 258-260.

- "Ethiopia: Drought intensifies in Tigray" IRIN (last accessed 8 December 2008

- Nyssen, J.; De Rudder, F.; Vlassenroot, K.; Fredu Nega; Azadi, Hossein (2019). Socio-demographic profile, food insecurity and food-aid based response. In: Nyssen J., Jacob, M., Frankl, A. (Eds.). Geo-trekking in Ethiopia's Tropical Mountains - The Dogu'a Tembien District. SpringerNature. ISBN 978-3-030-04954-6.

- Census 2007 Tables: Tigray Region Archived 2010-11-14 at the Wayback Machine, Tables 2.1, 2.4, 2.5 and 3.4.

- 1994 Population and Housing Census of Ethiopia: Results for Southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples' Region, Vol. 1, part 1 Archived 2008-11-19 at the Wayback Machine, Tables 2.1, 2.12, 2.19, 3.5, 3.7, 6.3, 6.11, 6.13 (accessed 30 December 2008)

- "Central Statistical Authority of Ethiopia. Agricultural Sample Survey (AgSE2001). Report on Area and Production - Tigray Region. Version 1.1 - December 2007" Archived 2009-11-14 at the Wayback Machine (accessed 26 January 2009)

- Vanmaercke, M. and colleagues (2019). "Sediment Yield and Reservoir Siltation in Tigray". Geo-trekking in Ethiopia's Tropical Mountains. GeoGuide. Cham (CH): Springer Nature. pp. 345–357. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-04955-3_23. ISBN 978-3-030-04954-6.

- Nigussie Haregeweyn, and colleagues (2006). "Reservoirs in Tigray: characteristics and sediment deposition problems". Land Degradation and Development. 17: 211–230. doi:10.1002/ldr.698.

- Nigussie Haregeweyn, and colleagues (2008). "Sediment yield variability in Northern Ethiopia: A quantitative analysis of its controlling factors". Catena. 75: 65–76. doi:10.1016/j.catena.2008.04.011.