Killingworth locomotives

George Stephenson built a number of experimental steam locomotives to work in the Killingworth Colliery between 1814 and 1826.

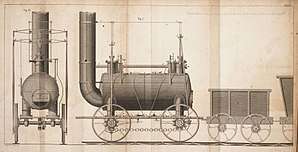

One of the Killingworth engines | |||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

Background

George Stephenson was appointed as engine-wright at Killingworth Colliery in 1812 and immediately improved the haulage of the coal from the mine using fixed engines. But he had taken an interest in Blenkinsop's engines in Leeds and Blackett's experiments at Wylam colliery, where he had been born. By 1814 he persuaded the lessees of the colliery to fund a "travelling engine" which first ran on 25 July. By experiment he confirmed Blackett's observation that the friction of the wheels was sufficient on an iron railway without cogs but still used a cogwheel system in transmitting power to the wheels.

Blücher

Blücher (often spelled Blutcher) was built by George Stephenson in 1814; the first of a series of locomotives that he designed in the period 1814–16 which established his reputation as an engine designer and laid the foundations for his subsequent pivotal role in the development of the railways. It could pull a train of 30 tons at a speed of 4 mph up a gradient of 1 in 450. It was named after the Prussian general Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher, who, after a speedy march, arrived in time to help defeat Napoleon at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815.

Stephenson carefully measured its performance and realised that overall it saved little money compared with the use of horses, even though the price of corn was at an all-time high because of the wars. He made one significant improvement by redirecting the steam outlet from the cylinders into the smoke stack, thereby increasing the efficiency of the boiler markedly as well as lessening the annoyance caused by the escaping steam.[1][2]

Blücher's performance was described in the second 1814 volume of the Annals of Philosophy. The item started by recording a rack locomotive at Leeds (probably Salamanca) and continued: "The experiment succeeded so well at Leeds, that a similar engine has been erected at Newcastle, about a mile north from that town. It moves at the rate of three miles an hour, dragging after it 14 waggons, loaded each with about two tons of coals; so that in this case the expense of 14 horses is saved by the substitution of the steam-engine". The item continues to mention a locomotive without a rack wheel (probably Puffing Billy at Wylam).[3]

Blücher did not survive: Stephenson recycled its parts as he developed more advanced models.

1815 locomotive

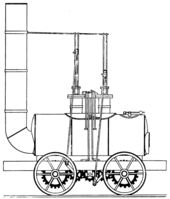

By 28 February 1815 Stephenson had made enough improvements to file a patent with the overseer of the colliery, Ralph Dodds. This specified direct communication between cylinder and wheels using a ball and socket joint. The drive wheels were connected by chains, which were abandoned after a few years in favour of direct connections. A new locomotive constructed on these principles was put into operation.

Wellington

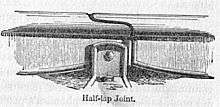

The big impediment revealed by the first two engines was the state of the permanent way and the lack of any cushioning suspension. The track was often carelessly laid and with rails of only 3ft in length there were frequent derailments. He devised a new chair and used half-lap joints between the rails instead of butt-joints. Wrought iron replaced cast iron wheels and he used the steam pressure of the boiler to provide 'steam spring' suspension for the engine. These improvements were detailed in a patent filed with the iron-founder Mr. Losh of Newcastle on 30 September 1816.

Together with the head viewer, Nicholas Wood, Stephenson conducted in 1818 a careful series of measurements on friction and the effects of inclines, or declivities as they were generally called, using a dynamometer which they developed.[4] These were to stand him in good stead in later developments of the railways.

Engines constructed on these principles from 1816 were being used until 1841 as locomotives and until 1856 as stationary engines. One of these was called Wellington and another My Lord.[5]

Killingworth Billy

The Killingworth Billy or Billy (not to be confused with Puffing Billy) was built to Stephenson's design by Robert Stephenson and Company[6] – it was thought to have been built in 1826 but further archeological investigation in 2018 revised its construction date back by a further decade to 1816[7]. It ran on the Killingworth Railway until 1881, when it was presented to the City of Newcastle-upon-Tyne. It is currently preserved in the Stephenson Railway Museum.

References

- Wood, Nicholas (1825), A Practical Treatise on Rail-roads and Interior Communication in General, London:Knight & Lacey, p. 147

- Smiles, Samuel (1862), "5", The lives of the engineers, 3

- Thomson, Thomas, ed. (1814), Annals of Philosophy, IV, Robert Baldwin, p. 232, retrieved 16 December 2014

- Wood 1825, pp. 169–201

- Hunter Davis (1975), George Stephenson, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, p. 44

- "Stephenson Railway Museum Exhibits". Archived from the original on 9 March 2012. Retrieved 6 May 2012.

- "BBC Look North". 14 June 2018.

- Herefordshire, The History of the Railway in Britain. Retrieved 25 January 2006.

- Monmouthshire Railway Society (Summer 1985), The Broad Gauge Story. Retrieved 25 January 2006.

- The Old Times – History of the Locomotive. Retrieved 25 January 2006.