Kerschenbach

Kerschenbach is an Ortsgemeinde – a municipality belonging to a Verbandsgemeinde, a kind of collective municipality – in the Vulkaneifel district in Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany. It belongs to the Verbandsgemeinde of Gerolstein, whose seat is in the municipality of Gerolstein.

Kerschenbach | |

|---|---|

Coat of arms | |

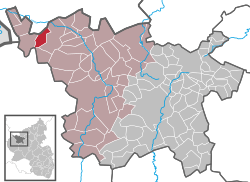

Location of Kerschenbach within Vulkaneifel district  | |

Kerschenbach  Kerschenbach | |

| Coordinates: 50°20′56″N 6°30′06″E | |

| Country | Germany |

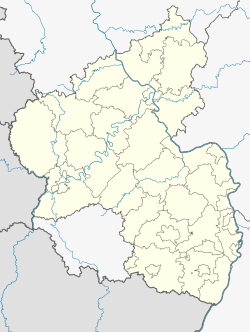

| State | Rhineland-Palatinate |

| District | Vulkaneifel |

| Municipal assoc. | Gerolstein |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Walter Schneider |

| Area | |

| • Total | 6.92 km2 (2.67 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 540 m (1,770 ft) |

| Population (2018-12-31)[1] | |

| • Total | 200 |

| • Density | 29/km2 (75/sq mi) |

| Time zone | CET/CEST (UTC+1/+2) |

| Postal codes | 54589 |

| Dialling codes | 06597 |

| Vehicle registration | DAU |

Geography

Location

The municipality lies in the Vulkaneifel, a part of the Eifel known for its volcanic history, geographical and geological features, and even ongoing activity today, including gases that sometimes well up from the earth.

Kerschenbach sits at an elevation of 550 m above sea level, and has an area of 691 ha. In the north, it borders on the state of North Rhine-Westphalia.

History

When Kerschenbach came into being is lost in the mists of time. The placename ending —bach points to beginnings in the time of the clearings in the Eifel, putting them in the 12th century.

The name “Kerschenbach” is closely tied to the like-named brook. In the 17th and 18th centuries, the village was called Kirschembach. The determinative Kerschen— goes back to the Old High German word kar, meaning “dale” or “hollow”. Kerschenbach therefore means “Dalebrook”

Unlike what has been unearthed in other, nearby municipalities, no traces of Roman occupation have come to light in Kerschenbach. There was some excitement when building works at the new village square brought up some ceramic piping that was thought might be Roman. However, the discovery turned into a disappointment when it became clear that the old pipes were actually the ones that had once been used to feed the old village drinking trough, and were not nearly old enough to be called ancient. Furthermore, they came not from Rome, but rather from the Kannenbäckerland (“Jug Bakers’ Land”, a small region still known for its ceramics industry) in the Westerwaldkreis, also in Rhineland-Palatinate.

In 1327, Kerschenbach had its first documentary mention when the knight Friedrich I von Kronenburg was enfeoffed with the dynastic castle along with a few surrounding villages, among which was Kerschenbach. From another document from 1345, one gathers that Counts Arnold I and Gerhard V, as Counts of Blankenheim, transferred, among other villages, Kerschenbach to King John of Bohemia, who was also Count in right of Luxembourg. For 2,000 Schildgulden, the comital brothers got the area back, but under the terms of the deal, they were obliged to help the Count of Luxembourg in times of war. In accordance with this document, Kerschenbach belonged under the Blankenheim lordship in the estate of Stadtkyll. In the end, almost the whole Eifel area passed to the Counts of Manderscheid. As of 1468, the Counties of Blankenheim and Gerolstein found themselves among this house's holdings and hence, so did Kerschenbach. In this time, Kerschenbach must have had a high court. In the 1488 agreement between Counts Cuno and Johann von Manderscheid dealing with the division of their inheritance, it comes to light that Count Cuno was awarded one half of all taxes, while his brother Count Johann was awarded not only the other half of this, but also the “high court at Kerschenbach”.

After the Thirty Years' War, only three families were left in Kerschenbach, headed by Theiß Webers, Gotthard Ebertz and Richard Holtz. The witch hunts that were being undertaken at this same time did not spare Kerschenbach women. As early as 1581, a woman named Katharina (Threin) Schligers had been put to death as a witch. This burning was one of the earliest in the High Eifel area. In 1633, another woman, Margarethe Heinen, fell victim to this madness.

The Plague brought not only hardship and misery to the area in the 17th century, but also it created a border oddity that persisted for quite a long time. Three families who had been living in a Kronenburg-held area moved to Kerschenbach as a result of the Plague outbreak, and although they now lived in Blankenheim-Gerolstein territory (estate of Stadtkyll), they remained Kronenburg-Luxembourgish subjects. In 1796, under French rule, these three families’ houses passed along with the Mairie (“Mayoralty”) of Kronenburg to the Department of Ourthe, whereas the village of Kerschenbach belonged to the Mairie of Stadtkyll in the Department of Sarre. Even ecclesiastically, these three houses went their separate way, passing in 1801 along with Kronenburg to the Diocese of Liège and in 1821 to the Archdiocese of Cologne. The Cologne Vicariate called Kerschenbach “part Spanish – part Gerolstein territory”. The two priests, one each from Stadtkyll and Kronenburg, got together on this matter and decided that they would both go about spiritual duties in Kerschenbach, of whichever of them it was asked, or whichever of them happened to be in Kerschenbach at any particular time.

After the time of French rule, this situation did not straighten itself out instantly. Instead, the three houses passed first under terms issued at the Congress of Vienna (1814-1815) along with Kronenburg to Meckenburg-Strelitz until 1819, when it became, again along with Kronenburg, part of Prussia’s Rhine Province, and more locally part of the Schleiden district in the Regierungsbezirk of Aachen. Kerschenbach, on the other hand, passed to the Bürgermeisterei (“Mayoralty”) of Stadtkyll and thereby in 1816 to the newly formed Prüm district. Owing to the many petitions, the whole village of Kerschenbach was eventually assigned to the Bürgermeisterei (later Amtsbürgermeisterei) of Stadtkyll, thus ending the saga of the three houses.

Since administrative reform in 1970, Kerschenbach has belonged to the Verbandsgemeinde of Obere Kyll in the Daun district, although this was renamed the Vulkaneifel district in 2007.[2]

Politics

Municipal council

The council is made up of 6 council members, who were elected by majority vote at the municipal election held on 7 June 2009, and the honorary mayor as chairman.

Mayor

Kerschenbach's mayor is Walter Schneider, and his deputies are Stephan Guthausen and Helmut Zapp.[3]

Coat of arms

The German blazon reads: Unter goldenem Schildhaupt, darin ein roter Zickzackbalken, in Rot durch silberne Wellenleiste gespalten, vorne ein aufgerichtetes goldenes Schwert, hinten eine goldene Ähre.

The municipality's arms might in English heraldic language be described thus: Gules a pallet wavy argent between a sword palewise, the point to chief and an ear of wheat, both Or, in a chief of the third a fess dancetty of three of the first.

The fess dancetty (horizontal zigzag) in the chief refers to Kerschenbach's mediaeval allegiance to the Lordship of Manderscheid-Blankenheim. The Counts of Manderscheid bore the red fess dancetty on a gold field in their arms. The silver wavy pallet (vertical wavy stripe) stands for the municipality's namesake brook. The chapel's and the municipality's patron saint is Saint Lucy, who died as a martyr by the dagger or sword. The gold sword, however, also refers to the mediaeval high court. Even today, the rural cadastral area named “Am Gericht” (“At the Court”) still recalls the former tribunal. The ear of wheat stands for what was for centuries the village's main livelihood: agriculture, and also for Kerschenbach's rural character.[4]

Culture and sightseeing

Buildings

- Saint Lucy’s Catholic Church (branch church; Filialkirche St. Lucia), Ormonter Straße 10, Late Gothic aisleless church, remodelled several times, among other times 1681, churchyard, grave crosses in churchyard wall, whole complex.

- Ormonter Straße 4 – house, part of an estate complex from 1777.

- Stadtkyller Straße 1 – timber-frame house, part of an estate complex, partly solid, roof with half-hipped gables, possibly from late 18th century.

- Stadtkyller Straße 6 – plastered bungalow.[5]

References

- "Bevölkerungsstand 2018 - Gemeindeebene". Statistisches Landesamt Rheinland-Pfalz (in German). 2019.

- Kerschenbach’s history

- Kerschenbach’s municipal council

- Description and explanation of Kerschenbach’s arms Archived 2011-07-19 at the Wayback Machine

- Directory of Cultural Monuments in Vulkaneifel district

External links

- Kerschenbach in the collective municipality’s Web pages (in German)

- Municipality’s official webpage (in German)