Kemp Law Dun

Kemp Law Dun is a vitrified fort dating from the Iron Age situated near the town of Dundonald in South Ayrshire, Scotland. The remains of the Iron Age fort or dun lie on the old Auchans Estate in the Dundonald Woods near the site of the old Hallyards Farm and the quarry of that name. The footpath route known as the Smugglers' Trail through the Clavin Hills from Troon to Dundonald runs passed the ruins of the dun. Kemps Law is in the order of two thousand years old.

Kemp Law Dun

| |

|---|---|

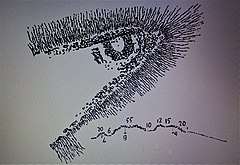

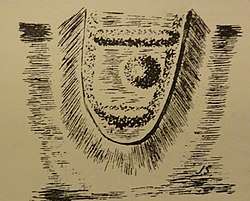

Drawing of the ruins of Kemp Law Dun in 1891 | |

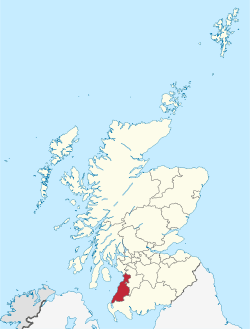

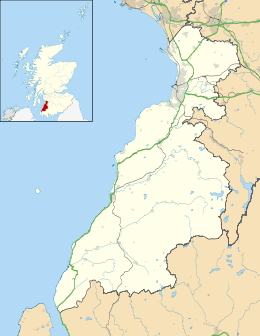

Kemp Law Dun Location within South Ayrshire | |

| OS grid reference | NS35583365 |

| Council area | |

| Lieutenancy area | |

| Country | Scotland |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | AYR |

| Postcode district | KA7 |

| Dialling code | 01292 |

| Police | Scotland |

| Fire | Scottish |

| Ambulance | Scottish |

| UK Parliament | |

| Scottish Parliament | |

History

The place-name 'Kemp' is found elsewhere in the south of Scotland, such as at 'Kemp's Castle' on the Lugar Water near Auchinleck Castle and at Kemps Castle near Sanquhar in Dumfries and Galloway.[1]

The antiquarian John Smith in 1895 visited Kemp Law and gives the place-name as meaning as 'battle hill' or 'warrior's grave'. He quotes a local as telling him "That's whaur th' brunt th' folk lang sine" and he speculates that after the dun was abandoned as a fortification it was used for cremations and over the centuries this would have resulted in the observed vitrification.[2] He dismisses the suggestion that the site was used as some sort of beacon due to its low lying position.[3]

A number of other ancient fortifications are present in the area such as those at Hillhouse,[4] Wardlaw Hill Fort Hillfort (NS35923276), Dun Donald Hillfort (NS36363451) and Harpercroft Hillfort Hillfort (NS36003252).

The scant remains of the chapel of St Mary and its associated holy well were still visible circa 1879 when Archibald Adamson visited Hallyards Farm. The chapel is thought to have been associated with Dundonald Castle.[5]

Structure

The dun lies in a well defended position on a minor ridge, but the site has been much disturbed and robbed of stone for building drystone dykes, etc. At Smith's time in the 1890s some stones were to be seen lying around and some of these were vitrified. On the northern side of the enclosure Smith identified a mound of stones, some eight feet in height.[3] The walls of the dun were in a ruinous state and it was clear that no lime mortar had been used in its construction.[3]

Thorbjorn Campbell refers to the mound as being formed from 'rubbish' and identifies an enclosing wall that runs round the edge of the promontory.[6] The stone walls are thought to have had timber interlacing and it is suggested that the deliberate burning of this timber resulted in the process of vitrification that supposedly strengthened the walls.[6]

James Paterson recorded the presence of a fosse or ditch on the west facing side which was not well protected by a steep declavity like the others sides. The fort was circular with a hollow passage covered with sandstone flags through which a person could crawl on hands and knees. This passage ran right round the structure.[7] A find was made here of an ear-ring like piece of iron, four inches in length. This artifact was exhibited at the Ayr Mechanics' Museum, still attached to a piece of vitrified stone.[7] By 1863 the fort had been robbed and was just a mound of rubble covered with vegetation.[7]

In 1891 Christison recorded the remains of a possible entrance on the east facing side of the fort.[8]

Dane Love records that the dun was 36 feet across internally and the internal walls were circa 14 feet thick. Circa ten feet from these internal walls are the remains of a second defensive wall.[4] The mound may have formed as a result of stone robbing.[9]

In one area the wall was found to be vitrified on the external face for half its thickness. A shale pin head was found here in 1963, similar to one found at Traprain Law.[9]

Vitrification

It is not clearly understood why or even how the stone walls were vitrified. Extreme heating has been shown to weaken the structure and an act of destruction seems unlikeley given that the walls to be vitrified would need carefully maintained fires for a lengthy period. Deliberate destruction following capture of the site or some form of ritual destruction by the ruling chief as an act of closure at the end of its useful life are other possibilities.

Etymology

The name "Kemp" is derived from Middle English kempe and from Old English cempa, meaning "warrior, knight, fighter or champion".[10] A kemp in Scots is a hero or a champion of great strength, and "Kemp" is a name applied to many hillforts, mottes, etc. throughout Scotland.[11]

The word dun denotes a kind of hillfort. The term originates in Scottish Gaelic as dùn. This style of fort is linked to the Celts from around the 7th century BC. The ramparts of duns were typically made of stone and timber with two walls, an inner and an outer. Vitrified duns are the remains that have been set on fire, resulting in some of the stones' melting and binding together. The word law is derived from the Old English word hlāw, meaning "hill".

See also

- Cairnduff - A Bronze Age cairn near Stewarton, East Ayrshire.

- Lawthorn - A Bronze Age round barrow and Moot hill near Perceton, North Ayrshire.

References

- Notes

- Kemp's Castle Vitrified Fort, Euchan Glen, Sanquhar A Vision of Britain Through Time

- Smith, page 120

- Smith, p.119

- Love, p.226

- Adamson, p.58

- Campbell, p. 197

- Patterson, p.435

- Christison, p.391

- Canmore Kemp Law Dun

- Wiktionary. The Free Dictionary

- "Dictionary of the Scots Language". Retrieved 16 December 2019.

- Sources

- Adamson, Archibald. Rambles Round Kilmarnock. Kilmarnock : Dunlop and Drennan.

- Campbell, Thorbjørn (2003). Ayrshire. A Historical Guide. Edinburgh : Birlinn. ISBN 1-84158-267-0.

- Christison, D. (1891) The Prehistoric Forts of Ayrshire. Proc. Soc. Antiq. Scot.

- Love, Dane (2003). Ayrshire : Discovering a County. Ayr : Fort Publishing. ISBN 0-9544461-1-9.

- Paterson, James (1863–66). History of the Counties of Ayr and Wigton. Vol. III - Cunninghame. Edinburgh: J. Stillie.

- Smith, John (1895). Prehistoric Man in Ayrshire. London : Elliot Stock.

External links

- Kemp Law Iron Age Vitrified Dun, Dundonald

- Cairn Duff Bronze Age burial mound, Stewarton

- Kemp's Castle Vitrified Fort, Euchan Glen, Sanquhar

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kemp Law. |