Kazakh-Dzungar Wars

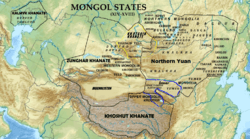

The Kazakh-Dzungar Wars (1643–1756) were a series of long conflicts between the Kazakh Juzes and Dzungar Khanate. The strategic goal for the Dzungars was to increase their territories by taking neighboring lands that were part of the Kazakh Khanate.[1] The Dzungars were not only seen as a threat by the Kazakhs, but for the rest of Central Asia and the Russian Empire itself. As a result of instabilities and local conflicts, as well as several wars with the Kazakh Khanate and the Qing Dynasty, the Dzungar Khanate ceased to exist when 90% of the population were killed by the Qing army in the Dzungar genocide.

| Kazakh-Dzungar Wars | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Dzungar Khanate | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

Erdeni Batur | ||||||

First Stage (1643–1718)

In 1643, the Battle of Orbulaq took place in the gorge of the Orbulaq River, in which 600 to 800 Kazakh warriors led by Jangir Khan with the support of 25,000 to 50,000 soldiers, aided by the Emir of Samarkand Jalantos Bahadur, who was from the Kazakh clan of Tortkara, successfully defeated 10,000 Dzungars.[2] Jangir Khan, participated in three major battles against the Dzungarian troops in 1635, 1643, and 1652 with variable successes. In 1680, the invasion by Galdan Boshugtu Khan of Semirechye and South Kazakhstan; the Kazakh ruler Tauke Khan was defeated, and his son was taken prisoner. As a result of the campaigns of 1683–1684, the Dzungars seized Sayram, Tashkent, Shymkent, and Taraz. In 1683, the Dzungarian army under the command of Galdan Boshoktu Khan's nephew, Tsewang Rabtan, reached Chach (present-day Tashkent) and the Syr Darya, by defeating only two Kazakh troops. In 1690, a war broke out between the Dzungar Khanate and the Qing Empire. The Kazakh Khanate, before the death of Tauke Khan in 1718, managed to resist the Dzungar invaders.

The campaigns led by the Dzungar troops in 1710–1719 caused a dispute and destabilization between the Kazakh clans, as each year the fear of a Dzungar invasion grew. Moreover, militarily the Dzungar Khanate represented a serious threat for the Russia, and even more so for the Kazakhs. Compared to some Asians who were used to a traditional warfare, the Dzungars, who had a large army, for the first time began using firearms and artillery at the end of the 17th century, as they purchased them from Russian gunsmiths and cast them off with a help of Johan Gustaf Renat, a former Swedish soldier who was held as a captive after being kidnapped by Dzungars during an expedition in Siberia. While the Kazakhs were armed with bows, sabers, and spears, these were largely inferior to the Dzungar weaponry. What's more, the only a few Kazakh warriors were equipped with rifles.

The invasion by Dzungars crippled the strength of the Kazakhs. Using their military superiority, the Dzungars troops temporarily seized part of Zhetysu, and the advancing forces also reached the Sarysu River in Central Kazakhstan as well. This sparked an alarm among the Kazakhs, and encouraged famous elders, biys, people's batyrs, and the most far-sighted Chingizids, to make efforts to unite the military and civilian potential of the three Juzes. The first Kurultai was held in the summer of 1710 in the Karakum district. The Kurultai set up a general Kazakh militia that was led by Bogenbai, who was seen as a prominent figure by others.

In 1711, a military force of the three Juzes managed to repulse the attacks. As a result, the Dzungars retreated to the east. In 1712, the Kazakh troops invaded the territory of Dzungaria which ended in a failure. Taking advantage of disagreements between the rulers of the three Juzes, including the Middle Juz that was led by three Khans, Bolat, Semyon, and Abulmambet, in 1714 the Dzungars made another sudden invasion of Kazakhstan. Kazakh militia in the spring of 1718 at the district of the River Ayaguz led by Kaip and Abulkhair Khan was defeated in the Battle of Ayaguz where 30,000 Kazakhs were attacked by a small Dzungar border detachment numbering only 1,000 men who tore down trees in the gorge and sat in an improvised trench for three days supporting each other while delaying the Kazakh army. On the last day, the Dzungar force of 1,500 people defeated the Kazakhs, who, despite overwhelming superiority in numbers and in firearms, couldn't withstand the Dzungar's brutal penetrating strike that involved a mounted horse attack and subsequent hand-to-hand combat which caused them to retreat.

Second Stage (1718–1723)

The foreign policy situation for the Kazakh Khan at the end of the 17th and early 18th century was difficult. From the west, the Volga Kalmyks and the Yaik Cossacks constantly raided the Kazakhs, with the Siberian Cossacks and Bashkirs from the north, Bukhara and the Khiva people from the south, but the main military threat came from the east, the side of the Dzungar Khanate, whose frequent military incursions into the Kazakh lands in the early 1720s was an alarming scale. A fearsome power in the east of the Dzungar Khanate, the Qing Dynasty, waited for a favorable opportunity to eliminate the Dzungars. In 1722, after the death of the Kangxi Emperor, who had been at war with the Dzungars for a long time, a truce was established on the border with China, which allowed for Tsewang Rabtan to focus more on the Kazakh lands. The aggression by the Dzungar Khanate, often referred by the Kazakhs as the "Years of the Great Disaster", that brought suffering, hunger, destruction of moral values, and caused an irreversible damage to the development of effective civilian force where thousands of men, women, and children were captured and imprisoned. The Kazakh clans, who paid a heavy price for their incompetent sultans and khans, under the pressure from the Dzungar troops were forced to abandon centuries-old inhabited land which led to displacement part of Kazakhs from the Middle Juz to the obstruction of the Central Asian khans. Many tribes of the Senior Juz also retreated to the Syr Darya river where they crossed it and headed toward Khujand. Kazakhs of the Younger Juz migrated along the Yaik, Ory, and Yrgyz rivers to the borders of Russia. As the conflict raged on, part of the Kazakhs of the Middle Juz settled in closer to the Tobolsk Governorate.

The "Years of the Great Disaster" (1723–1727) as its known by because of their destructive consequences which are often compared to the Mongol invasions of the beginning of the 13th century, the Dzungar military aggression significantly influenced the international situation in Central Asia. The thousands of approaching families to the boundaries of Central Asia and the relations with the Volga Kalmyks have worsened relations in the region. Kazahks, Karakalpaks, Uzbeks, attacking the weakened Kazakhs, worsened their already critical situation which particularly affected the Zhetysu in those years. Under the reign of Galdan Boshugtu Khan, large-scale military operations by the Dzungars were resumed. A mass movement of Kazakhs to the west caused a great concern among the Zhaiyks and the Volga Kalmyks. The new wave of Kazakhs who came to Zhayik was so large that the very fate of the Kalmyk Khanate was in question. This is evidenced by the request of the Kalmyk rulers to the Russian Tsarist government for military assistance to protect their summer nomads along the left bank of the Volga River. Because of it, in the middle of the 18th century, Zhaiyk became the border between Kazakhs and Kalmyks. The tremendous turmoil caused by the Dzungar invasions and a massive loss of basic wealth which was livestock led to an economic crisis that intensified political disputes among the ruling Kazakh elite.

Despite the fact that a new Dzungar–Qing war began in 1715, which lasted until 1723, Tsewang Rabtan continued military operations against the Kazakhs.

Third stage (1723–1730)

In 1723, Tsewang Rabtan was sent on a campaign against the Kazakhs, the Dzungars captured South Kazakhstan and Semirechye, defeating the Kazakh militia which lost the city of Tashkent and Sairam. The new Uzbek territories now included Khujand, Samarkand, and Andijan which were reliant on Dzungar protection. Furthermore, they captured the Fergana Valley as well.

In 1726, a meeting of representatives from the Kazakh juzes took place in Ordabasy near Turkestan, which decided to organize another militia. The committee chose Abilqaiyr Khan who was the leader of the Younger juz to be a commander of an army. After the meeting, the militia of the three Juzes united and were headed by Abilqaiyr and Bogenbai Batyr who in the Battle of Bulantin, defeated the Dzungar troops, which occurred in the foothills of Ulytau, in the Karasyir area. This was the first, over many years, a major victory for Kazakhs over the Dzungars that gained a moral and strategic recognition. The terrain where this battle took place was called "Kalma қırılғan" - "a place where the Kalmaks were exterminated".[3]

In 1726–1738, another Dzungar-Qing war began. As a result, the Dzungars were forced to retreat back to the western borders in a defensive position. In 1727, Tsewang Rabtan died which caused a rivalry between the contenders and heirs to the throne with most of the competition revolving around the sons of Tsewang Rabtan who were Lausan Shono and Galdan Tseren. Galdan Tseren, after defeating his brother Lausan Shono for the power, had to deal with a two-front war conflict.

From December 1729 to January 1730, near Lake Alakol, the Battle for Ańyraqaı took place, where 30,000 best warriors from all the three Kazakh juzes were led by Abilqaiyr Khan. Military operations took place in the territory of 200 km and according to a legend, the battle lasted 40 days and represented a lot of fights, confrontations of various units, clashes between the reoccurring locations at the mountain peaks. The number of soldiers from two sides, again according to different studies, range from 12,000 to 150,000 thousand men. The only thing that remains certain is that it was a victory for the Kazakhs. The Battle of Ańyraqaı played an important role in the victorious 200-year war conclusion of the Kazakh people where the Dzungar army was successfully defeated.

After the battle, the relationship between the Kazakh sultans was divided where Sultan Abulmambet migrated to the residence of Kazakh khans which was in Turkestan while Abilqaiyr hastily retreated to the territory of the Younger Juz. The sources do not mention the reasons for an inconsistent behavior by the Sultans despite them all fighting on the same side in the Ańyraqaı battle. It is believed that the main reason for the split between Kazakh khans was due to a struggle for complete power. After the death of Tauke Khan's son, Bolat, who was the khan of all three Juzes; Semek from the Younger Juz, and Abilqaiyr from the Middle Juz, both claimed the throne. The majority choice fell to Sultan Abulmbambet, the son of Bolat Khan. Semek and Abilqaiyr considered themselves neglected and because of it, they abandoned the battlefield, which was a morale blow to the campaign of liberating Kazakh lands from the Dzungarian invaders.

Fourth stage (1730–1756)

Despite the victory at Ańyraqaı by the Kazakhs in 1730, a new threat of another possible invasion by the Dzungar Khanate was still common due to its past aggression towards the Kazakh Khanate. Even the Kazakh khans themselves, including Abilqaiyr, did not give up their full desire to free Kazakh lands captured by the Dzungars, who imprisoned their fellow tribesmen as well. Tense relations by the Kazakh khans remained with Bukhara and Khiva, but by 1730s the Kazakhs managed to soften some of the disputes with the Central Asian khans; however, the relationship with the Volga Kalmyks and Bashkirs remained difficult. Obtaining peace on the western borders of the Younger Juz, and securing its rear was one of the main tasks of Abilqaiyr Khan. It was highly necessary for the Kazakhs to ease tensions with its neighbors in order to focus more on the Dzungars.

At the end of the 1730s, after concluding a truce with the Qing Dynasty, the ruling class of the Dzungar Khanate began active military-political preparations for another invasion of Kazakhstan and Central Asia. In the spring of 1735, Bogenbay Batyr informed the tsarist authorities that the Kazakhs who had escaped from the Dzungar captivity warned that Galdan Tseren was planning to send an army to attack the Kaisaks of the Middle Juz.

The invasion of Kazakhstan began in the autumn of 1739 with the total strength of around 30,000 troops. However, the khans and sultans of the Middle Juz only at the very last moment, when the invasion of the Dzungars had already begun, started to gather troops and preparing to repel the enemy. The political situation of the Middle Juz and the rest of Kazakh Khanate remained difficult. Local conflicts still occurred in the Younger Juz where part of the feudal lords, who were led by sultan Batyr, clashed with Khan Abilqaiyr. In 1737, after Sameke Khan of the Middle Juz died, he was replaced by Abilmambet. Despite him being elected to be a khan, Abilmambet was hesitant and did not enforce strong authority in the Kazakh steppe.

Thus, the Kazakh feudal lords still engaged in internal disputes and did not take any precautions to organize proper defenses on their borders. In the winter of 1739–1740. The Dzungar army struck in all directions. In the south, they came from the source of a Syr Darya river while in the North, they attacked from the Irtysh River, causing a considerable damage to the nomads of the Middle Juz.

In the autumn of 1740, new invasions by the Dzungar troops began on the territory of the Middle Juz. This time, the Dzungarian feudal lords had to face more a organized resistance. The Kazakh militiamen struck a number of unexpected blows by the Dzungars. These fierce battles were headed by the Abilmambet.

At the end of February 1741, the 30,000 strong Dzungar army, under the command of Septen and his elder son, Galdan Tsereng Lama-Dorji, again invaded Kazakhstan and reached Tobol and the Ishim river with skirmishes. The campaign lasted until the summer of 1741. During these battles against Dzungars, Abylai Khan, one of the prominent batyrs, was captured along with his companions. Commanding a small scout detachment of only 200 soldiers, Abylai burst directly into the location of the enemy's main forces. Surrounded on all sides by an army of thousands, the Kazakhs were captured. Shortly after not long fights, a small force of Sultan Barak was defeated as well. Sultan Durgun, batyr Akymshyn, Koptugan were captured and taken to Dzungaria.

In the summer of 1741, a council took place at the headquarters of the Middle Juz Khan. There were options to either continue the war or to start peace negotiations with the Dzungars. The majority spoke for peace, so a Kazakh ambassador was sent to Dzungaria which negotiated terms of an armistice and the release of prisoners, including Abylai Khan. The negotiations ended successfully and Abylai was released. This event contributed the start of feudal intolerance in the Dzungar Khanate where clashes took place for the throne of the Dzungarian Khong Tayiji.

As the fierce fighting took place in Dzungaria for power, concerns rose out about its future. The ruling Qing dynasty in China, which closely followed the developments in the Dzungar Khanate, considered the time to be the most suitable for delivering a final decisive blow to its weakened enemy.

In the early spring of 1755, a huge Qing army started another war with Dzungaria. The ruler, Dawachi, was captured and taken to Beijing. With the overthrow of Khong Tayiji, the Dzungar Khanate was split up into several groups of people that did not get along with one another and were at war with each other for their own leaders. Thus, the Dzungarian state, as a powerful militarized and centralized nation, essentially ceased to exist. By 1758, Dzungaria was in ruins and only represented fragments of its former power. The Qing Empire seized the present-day territory of Xinjiang, and its western boundaries extended to the east of Balkhash lake.[4]

The first half of the 18th century was not only a period of tragic misfortunes and heavy military defeats for the Kazakhs, but also a time of heroic deeds in the struggle against the Dzungars and other invaders. The weakness of the state power with the inability and unwillingness of the feudal elite who were engaged in internal strife instead of mobilizing the country's defenses prompted the most energetic, patriotic representatives of the Kazakh people to organize a fierce resistance against the enemies. In a war against the Dzungars, and the Manchu-Chinese invaders later on as well represent a whole group of brave warriors and skilled commanders who were: Bogembai, Qabanbai, Malaysary, Zhanibkek, Baian, Iset, Baygozy, Zhatay, Urazymbet, Tursynbai, Raiymbek and many others with Ablylai Khan being well known among them.

Aftermath

During the entire period of the Kazakh-Dzungar wars, the Dzungars fought on two fronts. In the west, they waged an aggressive occupational war against the Kazakhs, and in the east as well with the Qing Dynasty. The Kazakhs also fought on several fronts in which from the east with Dzungaria, the west where they were disturbed by Yaik Cossacks, Kalmyks and Bashkirs who constantly raided the border, and from the south against the states of Kokand, Bukhara, and Khiva.

After the death of the Galdan Tsereng in 1745 which caused an internal strife and civil war, by the struggle of candidates for the main throne and the disputes by the ruling elite of Dzungaria, one of whose representatives, Amursan, called for Chinese troops. As a result, the Dzungar Khanate fell. Its territory was surrounded by two Manchurian armies, numbering more than half a million people along with auxiliary troops from conquered people. Abylai chose not to take sides. He sheltered Amursana and Dawachi before from attacks by the Khoshut-Orait King of Tibet, Lha-bzang Khan. However, once Amursana and Dawachi were no longer allies, Abylai Khan took the opportunity to capture herds and territory from the Dzungars. More than 90% of the population of Dzungaria who were mostly women, old people, and children killed by the Qing army . About ten thousand families of Dzungars, derbets, and Hoyts, led by the Noyan and Tsereng, fought hard and went to the Volga of the Kalmyk principality. Some Dzungars made their way to Afghanistan, Badakhshan, and Bukhara who accepted military services by local rulers with their descendants eventually converting to Islam.

In 1771, the Kalmyks under the leadership of Ubashi-noyon embarked on a journey back to the territory of Dzungaria, hoping to revive their national state. This historic event is known as Torgutsky Escape or "Dusty Trek".[5][6][7]

In popular culture

Movies

See also

References

- "Казахско-джунгарские отношения.Нашествие джунгар 1723г — Мегаобучалка". Megaobuchalka.ru. Retrieved 17 June 2018.

- "Жангир-хан -". Famous.ukz.kz. Archived from the original on 13 January 2017. Retrieved 17 November 2018.

- "Political relationship between Kazakhs and Dzungars in the 17–18th centuries · Kazakh - Dzhongar war (XVII-XVIII c.) · Kazakhstan in Middle Age · History of Kazakhstan · "Kazakhstan History" portal". E-history.kz. Retrieved 17 June 2018.

- Museum, National Palace (14 February 2010). "The Lost Frontier – Treaty Maps that Changed Qing's Northwestern Boundaries_Demarcating and Signposting". Npm.gov.tw. Retrieved 17 November 2018.

- "3. Участие казахов в «Шаңды жорық» («Пыльном походе») (1771 г.) — bibliotekar.kz - Казахская электронная библиотека". Bibliotekar.kz. Retrieved 17 June 2018.

- 1.05m, Система Управления Контентом author™, версия. "«Тарих» - История Казахстана - школьникам - Путешествие во времени - «Пыльный поход» — финал двухсотлетней войны*". Tarih-begalinka.kz. Retrieved 17 June 2018.

- "УЧАСТИЕ КАЗАХОВ В «ПЫЛЬНОМ ПОХОДЕ» (1771 г.) - Новости Казахстана на сегодня, последние новости мира". Altyn-orda.kz. Retrieved 17 June 2018.