Karl Schmidt-Rottluff

Karl Schmidt-Rottluff (Karl Schmidt until 1905; 1 December 1884 – 10 August 1976) was a German expressionist painter and printmaker; he was one of the four founders of the artist group Die Brücke.

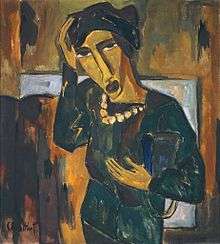

(c. mid-1910s)

Life and work

Schmidt-Rottluff was born in Rottluff, nowadays a district of Chemnitz, on 1 December 1884. He attended the humanistische gymnasium (classics-oriented secondary school) in Chemnitz, where he befriended Erich Heckel. He enrolled in architecture at the Sächsische Technische Hochschule in Dresden in 1905, following in Heckel's footsteps, but gave up after one term.[1] Whilst he was there, however, Erich Heckel introduced him to Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and Fritz Bleyl. They all passionately shared similar artistic interests and used architecture as a front to study art behind it. They founded Die Brücke in Dresden on 7 June 1905, with the aim of creating a style that was uncompromising and denouncing of all traditions. Its first exhibition opened in Leipzig in November of the same year.[2]

In 1906, Schmidt added his native town of Rottluff to his surname. He spent the summer of that year on the island of Alsen with Emil Nolde, where he convinced him to join Die Brücke. Being known as a loner of the group, Schmidt-Rottluff spent the summers on the coast at Dangast, near Bremen from 1907 to 1912.

From 1905 to 1911, during the group's Dresden stay, Schmidt-Rottluff and his fellow group members followed a similar path of development, and were heavily influenced by the styles of Art Nouveau and Neo-impressionism. Schmidt-Rottluff’s works stood out from his peers because of their balance of composition and simple form, which together served to exaggerate their flatness. He spent 1910 painting some of his most infamous landscape works that received recognition and fame. In December 1911, he and the other members of Die Brücke moved from Dresden to Berlin.[1]

The group was dissolved in 1913, largely due to the artist's independent moves to Berlin and a systemic shift in artistic direction from each individual member. Schmidt-Rottluff began to adopt more subdued coloring and placed greater emphasis in his pictures on draughtsmanship, which featured dark, contrasting lines between shapes rather than juxtaposing colors, which had previously been the norm. Around 1909 he was instrumental in reviving the woodcut as a beloved and usable medium. From 1912 to 1920, he adopted a much more angular style in his woodcuts and experimented with carved wood sculptures.

Schmidt-Rottluff served as a soldier on the Eastern Front from 1915 until 1918, but these experiences never heavily reflected in his artwork. At the end of the war he became a member of the Arbeitsrat für Kunst in Berlin, which was an anti-academic, socialist movement of German artists during the German Revolution of 1918–19. Schmidt-Rottluff’s angular, contrasting style became more colorful and looser in the early 1920s, and by the mid-1920s he began to evolve into flat shapes with gentle outlines. Through this development he remained committed to landscape painting as a whole.

The rewards and honors Schmidt-Rottluff received after World War I, as Expressionism gained recognition in Germany, were stripped from him after the rise to power of the Nazi Party. He was expelled from the Prussian Academy of Arts in 1933, two years after his admission[3] In 1937, 608 of Schmidt-Rottluff's paintings were seized from museums by the Nazis and several of them shown in exhibitions of "degenerate art". By 1941, he had been expelled from the painters guild and banned from painting. Much of his work was lost in the destruction of his Berlin studio in World War II, where he briefly returned to Rottluff afterwards to recover.[1] His reputation was gradually rehabilitated after the war. In 1947, Schmidt-Rottluff was appointed professor at the University of Arts in Berlin-Charlottenburg, where he would go on to exhibit a great influence on the new generation of German artists. An endowment made by him in 1964 provided the basis for the Brücke Museum in West Berlin, which opened in 1967 as a repository of works by members of the group.[3] He was a prolific artist, with 300 woodcuts, 105 lithographs, 70 etchings, and 78 commercial prints described in Rosa Schapire's Catalogue raisonné.

He died in Berlin on 10 August 1976.

Gallery of works

Schmidt-Rottluff, Seehofsallee in Sierksdorf, date unknown; from poster on an information table in Chemnitz

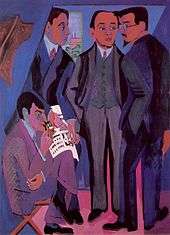

Schmidt-Rottluff, Seehofsallee in Sierksdorf, date unknown; from poster on an information table in Chemnitz Kirchner, Artist community, (1926/27) oil on canvas; painted after the Die Brücke years. (Schmidt-Rottluff on the right, with glasses.)

Kirchner, Artist community, (1926/27) oil on canvas; painted after the Die Brücke years. (Schmidt-Rottluff on the right, with glasses.)

Collections

Schmidt-Rottluff's works are included in the collections of, among others, the Museum of Modern Art, New York; the Neue Galerie, New York; the Los Angeles County Museum of Art; the High Museum of Art, Atlanta, GA[4]; and the Muscarelle Museum of Art, Williamsburg, VA.[5] The Museum am Theaterplatz in Chemnitz has a large collection of work from Schmidt-Rottluff.[6]

In 2011, the Neue Nationalgalerie returned two paintings by Schmidt-Rottluff, a 1920 self-portrait and a 1910 landscape titled Farm in Dangast, to the heirs of Robert Graetz, a Berlin businessman who was deported by the Nazis to Poland in 1942. A German government panel, led by former constitutional judge Jutta Limbach, had previously ruled that the loss was almost certainly a result of Nazi persecution and the paintings should be returned.[7] Schmidt Rottluff's esteemed Self Portrait with Monocle is now in the Staatliche Museum.

Art market

In 1997, £925,500 was paid for Schmidt-Rottluff's Dangaster Park (1910) at Sotheby's in London.[8] At a 2001 Phillips de Pury auction, British art dealer James Roundell bought Schmidt-Rottluff's The Reader (1911) for $3.9 million.[9] The top price ever paid at auction for a work by Schmidt-Rottluff was almost $6 million for Akte im Freien – Drei badende Frauen (Outdoor Nudes – Three Bathing Women) (1913) at Christie’s in London in 2008.[7]

See also

- Letter from Adolf Ziegler about the Nazi seizure of work

- Departure from the Akademie der Künste

Notes and references

- Carey, Frances; Griffiths, Anthony (1984). "Karl Schmidt-Rottluff". The Print in Germany 1880–1933. London: British Museum Publications. p. 123. ISBN 0-7141-1621-1.

- Grisebach, Lucius (2003). "Schmidt-Rottluff [Schmidt], Karl". Oxford Art Online. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- Karl Schmidt-Rottluff Museum of Modern Art, New York.

- "Frauenkopf (Head of a Woman)". High Museum of Art. Retrieved 2019-04-11.

- "Melancholie, (woodcut)". Curators at Work VI. Muscarelle Museum of Art. 2016. Retrieved 20 Jun 2018.

- Elizabeth Zach (July 27, 2012), In Germany, an Unlikely Art Hub Honed by Enthusiasm New York Times.

- Catherine Hickley (November 18, 2011), Berlin Will Return Paintings to Auschwitz Victim’s Heir Bloomberg.

- Souren Melikian (October 25, 1997), Great Substitution Game Generates High Stakes and Huge Profits International Herald Tribune.

- Carol Vogel (November 6, 2001), First Art Auction of Season Indicates a Healthy Market New York Times.

External links

- Schmidt-Rottluff's Cats