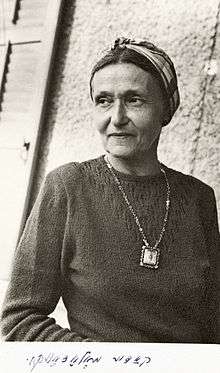

Kadia Molodowsky

Kadia Molodowsky (Yiddish: קאַדיע מאָלאָדאָװסקי — Kadie Molodovski; also: Kadya Molodowsky; May 10, 1894 in Byaroza – March 23, 1975 in Philadelphia) was a Russian-Jewish-born American poet and writer in the Yiddish language, and a teacher of Yiddish and Hebrew. She published six collections of poetry during her lifetime, and was a widely recognized figure in Yiddish poetry during the twentieth century.[1][2]

| |

| Born | May 10, 1894 Byaroza, Grodno Governorate, Russian Empire |

| Died | March 23, 1975 (aged 80) Philadelphia, United States |

| Language | Yiddish |

| Citizenship | Russian Empire, Poland, United States |

| Notable works | Poetry collections: Kheshvendike nekht: lider Dzshike gas and others |

| Spouse | Simcha Lev |

Molodowsky first came to prominence as a poet and intellectual in the Yiddish literary world while living in Warsaw, in newly independent Poland, during the interwar period.[3][4] Some of her more playful poems and stories were set to music and sung in Yiddish schools throughout the world.[5] She was also known for novels, dramas, and short stories. In 1935 she emigrated to the United States, where she continued publishing works in Yiddish.[3] She also went on to found and edit two international Yiddish literary journals, היים Heym (Home) and סבֿיבֿה Svive (Milieu).[6][7]

Biography

Born in the shtetl of Byaroza-Kartuskaya (now Byaroza), in the Grodno Governorate of the Russian Empire (present-day Belarus), Molodowsky was educated at home in both religious and secular subjects.[4] While her father, a teacher in a traditional Jewish elementary school (cheder), instructed her in the Hebrew Pentateuch, her paternal grandmother taught her Yiddish; with private tutors she studied secular subjects in Russian, including geography, philosophy, and world history.[2] Molodowsky's mother ran a dry goods story and, later, a factory for making rye kvass.[2]

Molodowsky finished high school at 17 years of age.[2] After then obtaining her teaching certificate in Byaroza, she studied Hebrew pedagogy under Yehiel Halperin in Warsaw, in 1913–1914, and, in the latter part of that period, instructed children there who had been displaced during the First World War.[2] In 1916 she followed Halperin to Odessa, where he had moved his course to escape the war front.[6] In Odessa, Molodowsky taught kindergarten and elementary school.[2]

In 1917, upon attempting to return to her hometown, she was trapped in Kiev, where she remained for several years; she lived through the pogroms that occurred there in 1919.[2]

While living in Kiev, Molodowsky was influenced by the Yiddish literary circle around David Bergelson,[8] and, in 1920, published her first poems, in the Yiddish journal Eygns (Our Own).[6] In 1921, she married the scholar and journalist Simcha Lev, and together they settled in Warsaw, now in independent Poland.[2]

In Warsaw, Molodowsky published her first book of poetry, Kheshvndike nekht (Nights of Heshvan), in 1927, followed by several others, including Dzshike gas (Dzshike Street), in 1933.[2][8] Throughout her years in Warsaw she taught Yiddish in secular elementary schools run by the Central Yiddish School Organization (Tsentrale Yidishe Shul-Organizatsye; TSYSHO); she also taught Hebrew in the evenings at a Jewish community school.[6]

Molodowsky emigrated to the United States in 1935 and settled in New York City, where her husband joined her not long after.[2] Among her works in the post-World War II period, she is especially noted for her collection Der melekh David aleyn iz geblibn (Only King David Remained; 1946), poems written in response to the Holocaust, including one of her best known poems, "Eyl Khanun" (Merciful God), composed in 1945.[7]

From 1949 to 1952 Molodowsky and her husband lived in Tel Aviv, in the new state of Israel, where she edited the Yiddish journal Di Heym (Home),[7] published by the Working Women's Council (Moetzet Hapoalot).[9] In late 1952 Molodowsky resigned her editorship of Heym, and she and her husband returned to New York.[10]

Back in 1943 Molodowsky had co-founded the Yiddish journal, Di Svive (Milieu), in New York, publishing seven issues through 1944;[7] around 1960 she revived the journal (under the same title) and continued to edit it until near the time of her death.[3] Her autobiography, Fun Mayn Elter-zeydns Yerushe (From my great-grandfather’s inheritance), appeared in serialized form in Svive from March 1965 to April 1974.[2]

In 1971, Molodowsky was honored as a recipient of the Itzik Manger Prize for Yiddish letters.[1]

Molodowsky's husband, Simcha Lev, died in New York City in 1974. In frail health, she moved to Philadelphia to be near relatives, and died in a nursing home there, on March 23, 1975.[11]

Poetry collections

- Kheshvendike nekht: lider. Vilna: B. Kletskin, 1927[6]

- Dzshike gas. Warsaw: Literarishe Bleter, 1933[6]

- Freydke. Warsaw: Literarishe Bleter, 1935[6]

- In land fun mayn gebeyn. Chicago: Farlag L. M. Shteyn, 1937[6]

- Der melekh dovid aleyn iz geblibn. New York: Farlag Papirene Brik, 1946[6]

- Likht fun dornboym. Buenos Aires: Farlag Poaley Tsion Histadrut, 1965[6]

Works in English translation (or bilingual editions)

- Paper Bridges: Selected Poems of Kadya Molodowsky (1999). Text in Yiddish and English translation, on facing pages. Translated and edited, and with an introduction by Kathryn Hellerstein. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. ISBN 9780814328460. Preview online

- A House with Seven Windows: Short Stories (2006). Translation by Leah Schoolnik, of A Shtub mit Zibn Fentster, first published in 1957. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press. ISBN 9780815608455

References

- "Kadya Molodowsky (1894-1975)." Jewish Heritage Online Magazine. Excerpt from: Kathryn Hellerstein, "Introduction," in Paper Bridges: Selected Poems of Kadya Molodowsky (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1999). Retrieved 2016-04-16.

- Hellerstein, Kathryn (20 March 2009). "Kadya Molodowsky." Jewish Women: A Comprehensive Historical Encyclopedia. The Jewish Women's Archive. Retrieved from www.jwa.org 2016-04-16.

- Klepfisz, Irena (1994). "Di Mames, dos Loshn / the Mothers, the Language: Feminism, Yidishkayt, and the Politics of Memory." Bridges. Vol. 4, no. 1, p. 12–47; here: p. 34.

- Braun, Alisa (2000). "(Re)Constructing the Tradition of Yiddish Women's Poetry." Review of Paper Bridges: Selected Poems of Kadya Molodowsky, by Moldowsky and Kathryn Hellerstein. Prooftexts. Vol. 20, no. 3, p. 372-379; here: p. 372.

- Liptzin, Sol, and Kathryn Hellerstein (2007). "Molodowsky, Kadia." Encyclopaedia Judaica. 2nd ed. Detroit: Macmillan Reference USA. Vol. 14, p. 429-430.

- Hellerstein, Kathryn (2 September 2010). "Molodowsky, Kadia." YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe. Retrieved 2016-04-16.

- Hellerstein, Kathryn (2003). "Kadya Molodowsky." In: S. Lillian Kremer (Ed.), Holocaust Literature. Vol. 2. New York: Routledge. p. 869-873; here: p. 870.

- Frieden, Ken. "Yiddish literature." Section: "'Modern Yiddish Literature: Yiddish Women Writers." Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 2016-04-16.

- Rojanski, Rachel (2012). "Yiddish Journals for Women in Israel: Immigrant Press and Gender Construction (1948-1952)." In: Marion Aptroot, Efrat Gal-Ed, Roland Gruschka, & Simon Neuberg (Eds.), Jiddistik heute / Yiddish Studies Today. Düsseldorf: Düsseldorf University Press. p. 585- 602; here: p. 590. ISBN 9783943460094. Article available online from the university's digital repository as a PDF file; retrieved 2016-04-16.

- Hellerstein, Kathryn (1999). "Introduction." In: Paper Bridges: Selected Poems of Kadya Molodowsky (pp. 17-51). Detroit: Wayne State University Press. p. 46.

- Hellerstein (1999), "Introduction," Paper Bridges, p. 50.

External links

- Guide to the Papers of Kadia Molodowsky. YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, RG 703