Justine Siegemund

Justine Siegemund or Siegemundin (26 December 1636 – 10 November 1705) was a renowned Silesian midwife whose Court Midwife (1690) was the more read, but not the first, female-published German obstetrical manual.[1]

Justine Siegemund | |

|---|---|

Justine Siegemundin | |

| Born | 26 December 1636 |

| Died | 10 November 1705 (aged 68) |

| Other names | Justine Dittrichs |

| Occupation | German writer |

Early life

She was born the daughter of Elias Diettrich, a Lutheran minister, in Rohnstock (now Roztoka), in former silesian Duchy of Jawor on December 26, 1636. Her father died in 1650, when she was aged fourteen. In 1655, she married Christian Siegemund, an accountant, but the marriage was childless. However, it lasted for forty-two years, and Christian Siegemund provided considerable support to his wife during her professional career, although they may have lived apart from 1673. Siegemund's childlessness should have technically disqualified her from her profession, as only childbearing midwives were supposed to be able to practice.

Early career: 1656–1672

At twenty, Justine Siegemund suffered considerably at the hand of incompetent midwives who wrongly assumed that she was pregnant. Her experience motivated her to educate herself about obstetrics, and she practiced herself for the first time in 1659, when she was asked to assist a case of obstructed labour related to a misplaced infant arm. Until 1670, she provided free midwifery services to peasant and poor women in her local area, although she also gradually diversified her client base to include women from merchant and noble families.

Professional midwife: 1670–1701 sqq.

Given her thriving midwife practice and expanding client base, Siegemund was called upon when a cervical tumour threatened Luise Duchess of Legnica, which she successfully removed, after male physicians called on her professional services. However, sexist professional animosities were never far away. In 1680, Martin Kerger, her former supervisor, turned on her and accused her of unsafe birthing practices. Unfortunately for Kerger, his own colleagues at the Frankfurt on Oder medical faculty sided with Siegemund instead, and it did not help that Kerger's own statements demonstrated that he lacked her practical experience-based professional knowledge of women's reproductive and infant anatomies and childbirth.

His groundless allegations did not affect Siegemund's professional employment opportunities, and in 1670 she was named the "city midwife" of Legnica/Lignitz. Her expertise and dexterity caught the attention of Frederick William, Elector of Brandenburg who appointed her as his court midwife termed the Chur-Brandenburgische Hof-Wehemutter in Berlin in 1683. She also served as royal midwife for Frederick III's sister Marie-Amalie, Duchess of Saxony-Zeitz, and delivered four of her children. At the court of August the Strong, she assisted Saxon Electress Eberhardine to give birth to her son, Frederick August II (1696). At the same time, she attended other births within the Berlin area.

While in the Netherlands, Mary II of Orange (1662–1694) suggested that Siegemund should author a textbook training manual for midwives. Siegemund had probably already started to compile the Court Midwife, however.

Siegemund rarely used early pharmaceuticals or surgical instruments within her practice. By the time that she died on November 10, 1705 in Berlin, Justine Siegemund had birthed almost six thousand two hundred infants, according to the Berlin deacon that presided over her funeral.

The Court Midwife (1690)

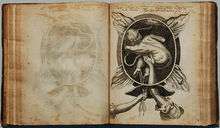

In 1689, Siegemund travelled from the Hague to Frankfurt on Oder, and submitted her draft manual to the Frankfurt on Oder medical faculty, which approved her medical documentation. She had incorporated embryological and anatomical engravings from Regnier de Graaf (1641–1673) and Govard Bidloo (1649–1713), which enhanced its practical utility. From April to June 1689, she protected her intellectual property stake in the volume through gaining printing privileges from the Electors of Brandenburg and Saxony, as well as the Holy Roman Emperor.

In Leipzig, she had to endure yet another bout of male professional jealousy when Andreas Petermann (1649–1703) charged her with similar offences to those that Kerger had already advanced, but given his own comparative professional inexperience, Siegemund once again was able to surmount this challenge to her professional reputation.

Based on careful notes that she had made during her deliveries she published an authoritative obstetrical text titled the Court Midwife (actually Die Kgl. Preußische und Chur-Brandenburgische Hof-Wehemutter) in 1690. It discusses its topics in the form of a dialogue between Justine (herself) and Christina, a pupil.[2] The Court Midwife was systematic and evidence-based in its presentation of possible childbirth complications, including problems like poor presentations, umbilical cord problems, and placenta previa and their management. In the textbook Siegmundin presented a solution to the delivery of a shoulder presentation, in those days often catastrophic situation leading to the death of the baby and potentially the mother. She worked out a two-handed intervention to rotate the baby in the uterus securing one extremity by a sling. She also is credited (along with François Mauriceau) of finding a method to deal with a hemorrhaging placenta previa by puncturing the amniotic sac.[3]

After Siegemund's death, the Court Midwife went through numerous republications, including Berlin (1708), Leipzig (1715,1724), with modifications that included corroborative male gynecological citations and accounts of the Kerger and Petermann cases when it was republished in 1723, 1741, 1752 and 1756.

Works

- Die königl[ich-]preußische und chur-brandenb[urgische] Hof-Wehe-Mutter : das ist: ein höchst nöthiger Unterricht von schweren und unrecht stehenden Gebuhrten, in einem Gespräch vorgestellet, wie nemlich durch göttlichen Beystand, eine wohl-unterrichtete Wehe-Mutter mit Verstand und geschickter Hand dergleichen verhüten, oder wanns Noth ist, das Kind wenden könne ; mit einem Anhange heilsamer Arzney-Mittel und ... Controvers-Schriften vermehret .... Berlin : Rüdiger, 1723 Digital edition of the University and State Library Düsseldorf.

Bibliography

- Waltraud Pulz: «Nicht alles nach der Gelahrten Sinn geschrieben» – Das Hebammenanleitungsbuch von Justina Siegemund. Zur Rekonstruktion geburtshilflichen Überlieferungswissens frühneuzeitlicher Hebammen und seiner Bedeutung bei der Herausbildung der modernen Geburtshilfe. München 1994. (Münchner Beiträge zur Volkskunde. Bd. 15.)(vorher Phil. Diss. München 1992.)

- Lynne Tatlock: "Speculum Feminarum: Gendered Perspectives on Obstetrics and Gynecology in Early Modern Germany" Signs: 17 (Summer 1992): 725–740.

- Waltraud Pulz: "Aux origines de l'obstétrique moderne en Allemagne (XVIe - XVIIIe siècle): accoucheurs contre matrones?" In: Revue d'histoire moderne et contemporaine 43 (1996), pp. 593–617.

- Waltraud Pulz: "Gewaltsame Hilfe? Die Arbeit der Hebamme im Spiegel eines Gerichtskonflikts (1680–1685)". In: Rituale der Geburt. Eine Kulturgeschichte. Hg. v. Jürgen Schlumbohm [u.a.] München 1998. (Beck'sche Reihe. 1280.) pp. 68–83, 314–318.

- Lynne Tatlock (translator): The Court Midwife: Chicago: University of Chicago Press: 2005: ISBN 0-226-75709-9

References

- "La sage-femme aux petites mains | Prendre corps". corpsgir.hypotheses.org. Retrieved 2015-12-12.

- Speert, Harold (1973). Iconographia Gyniatrica. F. A. Davis. p. 74. ISBN 0-8036-8070-8.

- Who Named It?. "François Mauriceau". Retrieved 2008-12-20.