Joshua James (lifesaver)

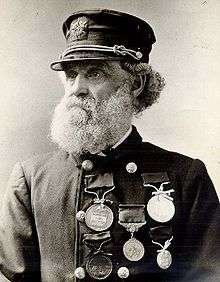

Joshua James (November 22, 1826 – March 19, 1902) was an American sea captain and a U.S. Life–Saving Station keeper. He was a famous and celebrated commander of civilian life–saving crews in the 19th century, credited with saving over 500 lives from the age of about 15 when he first associated himself with the Massachusetts Humane Society until his death at the age of 75 while on duty with the United States Life–Saving Service. During his lifetime he was honored with the highest medals of the Humane Society and the United States. His father, mother, brothers, wife, and son were also lifesavers in their own right.[1]

Joshua James | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | November 22, 1826 Hull, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Died | March 19, 1902 (aged 75) |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Awards | |

James was a recipient of the Gold Lifesaving Medal, awarded by the United States Government, along with four medals, a Certificate, and numerous monetary awards from the Massachusetts Humane Society.

Early life and education

Joshua James was born on November 22, 1826, in Hull, Massachusetts. He was the seventh of ten children to Esther Dill, who of Hull, Massachusetts, and William James who had emigrated from Dokkum, the Netherlands as a young man. Little is known of William James' early life except that he was a soldier in the Dutch Army before running away and becoming a sailor. In time he made his way to America, landing in Boston, where he earned a living as a sailor on numerous small schooners that provided paving stones to the city.[2] Eventually he made his home in Hull and via frugality became the owner of his own schooner and engaged in the paving-stone business for himself.

Esther Dill was the daughter of Nathaniel and Esther (Stoddard) Dill, of Hull, both descended from the early English colonists. Her great-grandfather, John Dill, who "for a number of years," was the skipper of the boat which supplied the market at Oliver's Dock [Boston] with fresh fish." Three of Esther's uncles, Daniel, John, and Lemeul, a "famous drummer," served in the Continental Army under George Washington during the Revolutionary War. Another uncle, Samuel, appears to have died in the Maine wilderness while serving with General Benedict Arnold's expedition against Quebec in 1775. Esther's father, Nathaniel (1756-179?), occasionally mustered as a fifer, spent most of his Revolutionary War service at Boston Harbor forts, but also appears to have served in the Continental Army early in the War. One of Esther's brothers, Nathaniel, lost his life aboard the 32-gun wooden frigate USS Boston during its engagement and capture of the 22-gun French corvette Berceau in 1800 at the end of the Quasi-War with France, while another, Caleb, died on a military expedition to Canada during the War of 1812. Esther Dill was the only girl in a family of seven children and was sixteen at the time of her marriage to William James in 1808.[2] Not long after Joshua's birth, about 1829, William James purchased the Dill home by the sea along present-day James Avenue in Hull. He was a Lutheran, and it was his custom to read from the Bible he brought with him from the Netherlands. When his children were old enough they were required to read every morning in English from the King James version of the Bible. During Joshua's childhood, there were occasional Methodist itinerant preachers who visited Hull as they had for decades. There was no church building save a one-room schoolhouse prior to construction of a Town Hall in 1848.

He was described by his elder sister Catherine that he had a thoughtfulness and reserve that distinguished him from other children. He was the favorite of his father, beloved by his brothers, idolized by his sisters.[2] Joshua was a great reader from childhood on, preferring historical and scientific books, notably astronomy. His preference for practical literature is most likely due in part to his parents, whose strict religious views largely guided the children's choice of reading. Esther Dill prohibited the reading of novels and fiction of all kinds, and forbade the neighbors lending her children novels. On one occasion she destroyed a beautiful and expensive copy of The Children of the Abbey that she found in the hands of one of her daughters.[2]

On April 3, 1837, at the age of 10, Joshua witnessed a pivotal event in his life; he was an eye-witness to the death of his mother and a baby sister in the shipwreck and sinking of the schooner Hepzibah[A] in Hull Gut, only a half-mile from safe harbor. Mrs. Ester James was returning from a visit to Boston in the Hepzibah, a paving-stone hauling vessel owned by her son (his brother) Rainier James. As they were passing through the treacherous Hull Gut, a sudden squall threw the vessel on her beam; the Hepzibah filled and sank before Mrs. James and her baby, who were in the cabin, could be rescued.[1] This event was no doubt influential in shaping Joshua's life. His older sister by five years, Catherine, took over the raising the family after the death of their mother.[2]

At a very early age Joshua began to go to sea with his father and his elder brothers, Rainer and Samuel. There his fondness for astronomy stood him in good stead, and he soon became an expert navigator. His father in later years was fond of relating incidents illustrative of Joshua's good seamanship and the confidence reposed in him by other sailors. William James continued in the paving-stone trade between Hull and Boston until cobblestones were replaced by more modern paving materials. At one time he had a large contract for filling in the west end of Boston, and owned a fleet of twelve vessels of from 50 to 125 tons burden.[2] It was his practice to give each of his sons on reaching the majority age of 25 a complete outfit for the business, including a new schooner. Joshua, with his deep love of the sea and his early training on his father's and brothers' vessels, was a natural seaman, and with such an outfit provided by his father, entered business for himself, lightering and freight-carrying. Captain Joshua James, as he now came to be called, continued in his chosen profession until his appointment as keeper of the Point Allerton Life–Saving Station in 1889.[2]

Career

Joshua's lifesaving activities began on December 17, 1841, when he was just 15 years old. Five years after the death of his mother and sister, Joshua James leaped aboard a surfboat manned by volunteers from the local chapter of the Massachusetts Humane Society at Hull heading toward the ship Mohawk which was being "hammered shapeless" off Allerton Beach at Harding's Ledge. He would continue to save lives for the next six decades as a member of the Massachusetts Humane Society and later the U.S. Life–Saving Service .

By 1886 he was involved in so many rescues that the Humane Society struck a special silver medal for "Brave and faithful service of more than 40 years." The report said, "During this time he assisted in saving over 100 lives."[1] However, many records of his early rescues were lost when the archives of the Massachusetts Humane Society were destroyed in the Great Boston Fire of 1872.

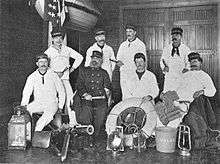

Appointment as U.S. Life–Saving Service keeper

In 1889 the U.S. Life–Saving Service established Point Allerton Station at Hull, Massachusetts. James was 62 years old, seventeen years past the mandatory retirement age of 45 for a federal appointment with the new U.S. Life–Saving Service. Due to his unequaled lifesaving record, considerable petitioning by townspeople of Hull and his allies in the service Congress made a special provision to allow him to be appointed as keeper of the new station. Under the question on the form calling for past experience qualifying him for the position he wrote "fisherman."[1]

Significant rescues

Hurricane of 1888

The hurricane of 1888 came in the guise of a northeast gale and snowstorm accompanied by extremely high tides, and 100 mph (155 km/h) winds created tremendous surf conditions. The snow and sleet in the early part of the storm gave way to rain. Early in the day of November 25, 1888, Captain James and a few hardy beachmen climbed to the top of Telegraph Hill, where through nearly blinding snow and wind they observed five schooners and one coal barge anchored off an area southeast of Boston called Nantasket, attempting to ride out the storm.[4] With the intensity of the storm growing and sensing that it was only a matter of time before some of the ships at anchor yielded to the storm, Captain James notified his volunteers to be ready for service, and about two o'clock ordered patrols all along the ocean shore.[2]

The beach patrols had hardly begun when the schooner Cox and Green was discovered broadside to the beach. When Captain James judged the seas too heavy to risk launching a rescue boat, the beach apparatus was called upon. With the assistance of local residents Captain James and his men rescued the entire crew by rigging a breeches buoy to the stricken schooner.[4] This was to be the first rescue of an extraordinary 36 hours during which 28 Hull volunteers would work in five crews to save 29 lives along the town's shores.

No sooner than the last crewman from the Cox and Green was safely ashore the schooner Gertrude Abbott had struck some rocks about one-eighth mile to the east of the Cox and Green and was too far out to reach with the line and breeches buoy.[5] Because night was approaching, the incoming tide was very high and the storm increasing in fury, Captain James decided the best course was to wait until low tide the next day. He ordered the surfboat R.B. Forbe brought on the beach abreast of the Gertrude Abbott and a bonfire lit on a bluff so the stricken vessel could be kept in view.[4][B] During the evening, weather and sea conditions deteriorated so much that between 8:00 pm and 9:00 pm the crew chose to row out to the Gertrude Abbott during the night. Knowing that the conditions were extremely dangerous, Captain James told the men that only volunteers would be taken for the rescue attempt; all the men volunteered.

They launched the surfboat R.B. Forbe through the breaking waves and rowed to the wrecked Gertrude Abbott with two of the crew bailing constantly to keep the boat from swamping. After desperate rowing the R.B. Forbe maneuvered under the ship's bow and a line was heaved from the surf boat to the schooner, and as the smaller craft was lifted by the cresting waves the eight sailors leaped one by one from the rigging into the surfboat. With 17 men aboard, they began the hazardous return journey to shore. Between rescuers and survivors, the R.B. Forbe was overcrowded, leaving little room to work the oars. The overcrowding also made the boat even more difficult to manage. Within two hundred yards of the beach, the R.B. Forbe struck a rock, rolled one gunwale deep under water, and began taking on seawater. The occupants quickly shifted their position and succeeded in righting the boat. One surfman was washed out of the boat by a wave, but was reclaimed by his comrades before the sea carried him away. The surfboat was buffeted along at the mercy of the waves and struck rocks a number of times. With most of the oars lost or broken, the men managed with the few oars left to steer the R.B. Forbe toward the shore so that the waves might push her in. Captain James admonished everyone to stick to the boat as long as possible. Finally near shore the R.B. Forbe was thrown upon some hidden rocks and completely wrecked. The occupants promptly jumped out and scrambled to shore and safety.[4] The schooner's crew were immediately taken to a neighboring house and cared for. For the rescue that Captain James himself called "miraculous," all nine surfmen were awarded the Treasury Department's U.S. Gold Lifesaving Medal, the highest possible award.[6][7][8][C]

Because the storm continued, Captain James ordered the surfmen to maintain a patrol along the beach to watch for more wrecks. At 3:00 a.m. word came of a third wreck, of the schooner Bertha F. Walker. This time the vessel had sunk and seven crewmen were stranded in her rigging. As the surfboat R.B. Forbe had been wrecked in the rescue of the Gertrude Abbott, volunteers had to drag a second surfboat, the Robert G. Shaw four miles overland with the help of horses to the site of the wreck. At dawn, James and the rescuers were able to launch the second boat from the protected launch at Pemberton Point, but faced a six and a half mile row in difficult seas to reach the Bertha F. Walker and save the seven men in her rigging, who were in danger of perishing of exposure.

Just as they landed ashore with the seven men from the Bertha F. Walker, word came of two more shipwrecks, the H. C. Higginson and the Mattie E. Eaton. In addition to Joshua and his crew of the Massachusetts Humane Society, the crew of the U.S. Life–Saving Service station at North Scituate and Cohasset had also gone to the rescue of the H. C. Higginson. Captain James and his volunteers had to pull their beach cart with rescue equipment nine miles overland through snow and slush to get to the wreck site. Efforts to fire lines out to the H. C. Higginson failed due to debris fouling the lines, and the Cohasset and Scituate crews left the wreck site, so it was necessary to launch the untested surfboat, the Nantasket.[D]

The rescue was extremely dangerous because the waves were breaking around the wrecked H. C. Higginson. Captain James took the Nantasket out twice. The first attempt failed after forty-five minutes of rowing when the boat hit rocks that knocked two holes in it, making it necessary to return to shore to make temporary repairs using lead patches. On the second attempt, the Nantasket was rowed close enough to the schooner for the men to throw a line on board the H. C. Higginson. The first sailor to be rescued was in the mizzen rigging; he came cautiously down the shrouds, tied the line around his body, leaped overboard into the sea, and was hauled into the surf boat. Four other sailors in the fore rigging, exhausted from their long exposure, had to work their way with great difficulty into the main rigging. There they fastened lines to themselves and in turn jumped into the breaking waters and were hauled one by one into the Nantasket. Once in the surf boat, they were taken safely to the shore, where the half-starved and half-frozen men were quickly conveyed in carriages to the home of Selectman David O. Wade of Hull. Not all of the crew of the H. C. Higginson were so fortunate. Three lost their lives: the captain and one sailor were washed overboard in the night and a third man died in the rigging from exposure.

By the time they were able to reach the site of the Mattie E. Eaton, the wreck had come so far up on the shore that her crew was able to get off on their own. The brigantine Alice was abandoned at sea, but late on the 26th the vessel had come ashore. Two salvors had gone aboard and needed to be rescued when their dory was swept away. Captain James and his crew took the would-be salvors off the wrecked Alice. The Alice was the last rescue of the Hurricane of 1888.

For his work at the scene of six wrecks during a two-day period and rescuing 29 people, Joshua James was awarded gold medals by both the Massachusetts Humane Society and the U.S. Life–Saving Service.[9] James' United States Gold Lifesaving Medal is now in the collection of the United States Coast Guard Museum at the United States Coast Guard Academy in New London, Connecticut. The U.S. Life–Saving Service also awarded eleven gold and four silver medals to the other volunteers for their heroic efforts. The 1888 storm led to the construction of the Point Allerton U.S. Life–Saving Station one year later.[10]

Hurricane of 1898

The storm started quietly on the evening of the 26th of November 1898 with a light but strengthening wind. Within hours the winds had grown to hurricane proportions and was creating havoc all along the coast. The winds raged all through the night of the 26th, all day on the 27th, and did not subside until the 28th. Some 36 hours after the storm had started winds were clocked at up to 72 mph in Boston and were probably even stronger along the coast to the southeast on Cape Cod.

At about 3:00am surfman Fernando Bearse who was on patrol spotted a schooner about a quarter mile from land directly in front of the station. With the surf pounding hard and the wind blowing strong it was decided against launching the surfboat. Around 6:30 am the Henry R. Tilton had swept westward and was now within range of the Lyle gun. Captain James' first two shots were unsuccessful, but the third shot landed within reach of the crew on board who quickly secured the whip line to the foremast twenty feet above the deck. After bringing the first sailor ashore the rescuers realized that the Henry R. Tilton was still drifting toward shore. After each transfer of a crewmen from ship to shore the rescuers had to reset the lines. The men handling the lines had to wade out into the water and were standing dangerously close to the breaking waves. From time to time the sea would engulf the men and equipment. It took over three hours with a mixed crew of U.S. Life-Saving men and Humane Society volunteers to bring all seven crew members of the Henry R. Tilton to safety. Back at the Point Allerton Station, Louisa James and the wives of the other surfmen had lit fire in the station's stove, laid out blankets, hot drinks and cared for the surviving crew of the Henry R. Tilton. After enduring 15 hours of riding out the storm the crew of the Henry R. Tilton could finally feel safe.[10]

At about the time Captain James and his crew completed their rescue of the Henry R. Tilton, word came that Coal Barge No. 1 of the Consolidated Coal Company was coming ashore about three-quarters of a mile west of their location on Toddy Rocks. The storm had blown down telephone, telegraph, and electrical lines in front of the Point Allerton station making it impossible to drag out the station's second beach rescue apparatus. Joshua James conferred with his son Osceola James, who was Captain of the Hull chapter of the Massachusetts Humane Society on the best course of action. The two agreed that Osceola would send some of his men to Massachusetts Humane Society's Station #18 to retrieve the Hunt Gun stored there and Osceola would rent some horses to bring the rest of the equipment. The rest of the men went to the wreck site.[E][11]

At about 11:00 pm the two crews reached the wreck site and set up the Massachusetts Humane Society's beach apparatus. While they were firing shots from the Hunt Gun, they realized that Coal Barge No. 1 was about to break up. Both keepers called for volunteers to wade out into the surf. The volunteers tied lines to their waists and walked out amidst debris to get as close to the vessel as possible. While they were wading out to the stranded barge, the pilothouse broke free from the vessel and rode the waves toward the shore. Close to shore the waves slammed the pilothouse to pieces, tossing its passengers into the surf. The volunteers already in the water rushed to grab the survivors before the rip current could drag them away. With the surfmen holding on to the sailors they waited for waves to carry them to a point on the beach where they could scramble to safety.

On the morning of the 27th, Captain James using his spy glass spotted a predetermined distress signal at Boston Light on Little Brewster Island. The U.S Life–Saving crew and four volunteers launched the Humane Society's surfboat #17, Boston Herald from Stony Beach.[12] En route Captain James spotted the steam tug Ariel and arranged to be towed as close as possible to Great Brewster Island. After being brought as close as possible to the island, the surfmen rowed the Boston Herald through the breaking surf and came alongside the schooner Calvin F. Baker. Five survivors were retrieved. At 3:00 am on the 26th the Calvin F. Baker had run aground on the island and remaining eight crew members were forced into the bow rigging. They would remain in the rigging for the next thirty hours. During that time the First Mate and Second Mate could not hold on and fell into the water and drowned. The Steward froze to death in place. His body was carried down to the surf boat by the rescuers. After rowing the Boston Herald back through the breaking surf and to Stony Beach, the survivors of the Calvin F. Baker warmed themselves in front of the fire with fourteen other lucky survivors at the Point Allerton Station.[F][13]

Houses were blown over and washed away all along the coast from Cape Cod to Portland, Maine. The coastline was littered with the wrecks and wreckage of dozens of vessels large and small, smashed or sunk by the fierce winds and seas. In Provincetown harbor alone over 30 vessels were blown ashore or sunk. Damage along Boston's south shore and Cape Cod was probably the worst. Telegraph lines were brought down, railways washed out, and even the low scrub trees of Cape Cod were blown away. In Scituate, the coastline was permanently altered when mountainous waves cut a new inlet from the sea to the North River, closed the old river mouth and reversed the flow of part of the river.

As with the hurricane of 1888 there were numerous brave rescues in an extraordinary 36 hours, during which the crew of the Point Allerton station and volunteers from Hull would save 41 lives along the town's shores.

The schooner Ulrica

On December 15, 1896, a northeast storm with gale-force winds and heavy snow struck the Massachusetts coast. The Ulrica, a three-masted schooner with a load of plaster southbound for Hoboken, New Jersey was caught in the storm. The ship turned for Boston Harbor to ride out the storm. When the winds shredded her sails she ended up dropping both of her anchors off Hull near Nantasket beach. Her anchors failed to hold and at about 8:00 am on December 16, 1896, she was observed aground by a patrolling surfman from the Point Allerton Station who promptly reported the wreck. News of a ship in trouble had already been telephoned to the station and Captain James accepted the railroad's offer to transport the rescuers the two and a half miles to the wreck site. One surfman was left behind to obtain horses and bring the beach cart to the scene.

On arrival at the wreck site, they found very heavy seas breaking over the Ulrica forward of the mizzen mast. The crew had taken refuge in the aft house and the mizzen rigging. Concerned that the crew was in great danger Captain James decided not to wait for the beach cart and retrieved the Nantasket from the Massachusetts Humane Society which was housed nearby. A mixed crew of seven Life–Saving Service men and six volunteers from the Humane Society launched the large surfboat only to be hurled back to the beach twice by the strong waves. The third launch attempt was successful, but progress was slow due to the strong current. At one point about halfway to the wreck a large wave struck the Nantasket astern, throwing Captain James out of the boat. He caught an oar as the boat passed him and was hauled back aboard the Nantasket.

In the interim the beach cart had arrived and it was decided to try the breeches buoy to effect a rescue. Two shots from the Lyle Gun were fired across the Ulrica, but the crew was too cold to retrieve the line. The third shot fell close enough for the crew to grab the line, but because of the crew's exhausted state they were unable to make the line fast high enough in the rigging. Under these conditions Captain James thought it was too dangerous to use the breeches buoy and decided to make another attempt using the surfboat.

Once more with a mixed crew of seven Life–Saving Service men and five volunteers from the Humane Society, they attached the surfboat to the hawser via the traveler block and fastened the other line to the stern of the surfboat. Using a combination of oars and hand hauling on the hawser and aided by men on shore controlling the stern line. They managed to bring the Nantasket to the Ulrica. All seven crew members of the Ulrica were brought safely to shore and were taken to Seafoam House to recover before being taken to the Station. For this difficult rescue Captain James received the silver medal from the Massachusetts Humane Society.[14][15][16][G]

Known rescues

- December 17, 1841, assisted in the rescue of twelve crewmen of the Mohawk.[17][18][19]

- October 10, 1844, assisted in the rescue of eight crewmen of the brig Tremont.[20][21][22]

- December 9, 1845, assisted in the rescue of crew of the Massasoit.[23]

- April 1, 1850, assisted in the rescue of crew of the brig L'Essai.

- April 1, 1850, assisted in the rescue of crew of the Delaware.[24]

- March 2, 1857, assisted in the rescue of crew of the brig Odessa.

- December 23, 1870, assisted in the rescue of the crew of schooner William R. Genn.[24]

- March 15, 1873, assisted in the rescue of the crew of the Helene.[24]

- February 1, 1882, assisted in the rescue of the crew of the Bucephalus.[24]

- February 1, 1882, assisted in the rescue of the crew of the Nellie Walker.[24]

- Date unknown 1883 assisted in the rescue of the crew from the schooner Sara Potter.[24]

- February 17, 1884, assisted in the rescue the crew of the brig Swordfish.[24]

- December 1, 1885, assisted in the rescue of the crew of the brig Anita Owen.[24][25]

- January 9, 1886, assisted in the rescue of the captain of the Millie Trim, but was unable to save the rest of the crew.

- November 26, 1886, assisted in the rescue of the crew from the schooner Bertha F. Walker.[26][27][28]

- November 26, 1886, assisted in the rescue of the crew from the schooner H.C. Higgins.[29]

- December 25, 1888, assisted in the rescue of nine men from the schooner Gertrude Abbott.[7][30][31][32]

- November 25, 1888, assisted in the rescue of the crew from the schooner Cox and Green.[25][30]

- November 5, 1891, assisted in the rescue of the crew from the schooner Clara S. Cameron.[33]

- August 26, 1892, attempted rescue of the steamer W.S. Slater, no crew members were found[34][35]

- February 19, 1893, assisted in the rescue of seven crewmen from the schooner Enos Phillips.[36][37]

- February 22, 1893, opened the station to take in the crew of the Glenwood who abandoned their wrecked vessel off Hardings Ledge.

- April 8, 1894, assisted in the rescue of seven men from the schooner Mary A. Hood.[38][39]

- December 16, 1896, assisted in the rescue of the crew from the schooner Ulrica.[40][41][42]

- December 16, 1896, assisted in the rescue of the crew from the Modesty.[43]

- February 2, 1898, assisted in the rescue of the crew from the schooner Albert Crandall.

- November 27, 1898, assisted in the rescue of four men from the schooner Virginia.[44]

- November 27, 1898, assisted in the rescue of one survivor from the Able E. Babcock.[44][45]

- November 27, 1898, assisted in the rescue of five survivors from the schooner Calvin F. Baker.[45][46]

- November 27, 1898, assisted in the rescue of seven men via breeches buoy from the Henry R.Tilton.[44][46]

- November 27, 1898, opened the station to a family whose home was threatened by the storm.

- November 27, 1898, assisted in the rescue of three men from the beached Coal Barge No. 1.

- November 27, 1898, assisted in the rescue of five men from the beached Coal Barge No. 4.

- November 28, 1898, assisted in the rescue of three men from Black Rock after loss of their vessel Lucy A. Nichols.

- November 28, 1889 assisted in the rescue of seventeen survivors of the wreck of the tug H.F. Morse.

- November 27, 1898 assisted in the rescue of four men from the schooner Virginia[47]

- February 25, 1900, assisted in the attempted rescue of the Keystone, no survivors.[48]

- February 25, 1900, assisted in the rescue of five men from the Otto.[49][50]

- October 7, 1901, assisted in the rescue of five men from the schooner Columbia.[51]

Possible rescues

It is very likely that Joshua James led or participated in the following rescues.

Offices

- 1876, appointed keeper of 4 Massachusetts Humane Society life–boats at Stony Beach, Point Allerton, Nantasket Beach, Gun Rock Cove and a mortar station at Gun Rock Cove.[53]

- October 22, 1889, James took the oath of office as keeper of the U.S. Life–Saving Station at Point Allerton.

At 62, James passed all of the physical examinations with no difficulty and eleven years later at 73 he repeated the act.[H] During the thirteen years he was keeper of the Point Allerton station he and his crew saved 540 lives and $1,203,435.00 worth of estimated value of ships and cargo.

Death

The dramatic death of Joshua James occurred on March 19, 1902. Two days earlier all but one the Monomoy Point Life–Saving Station crew perished in a rescue attempt, drowned by the panicked victims of a ship wreck they were attempting to save. The tragedy affected Joshua deeply and convinced him of the need for even more rigid training of his own crew. At seven o'clock the morning of March 19, with a northeast gale blowing, James called his crew for a drill and to test a new self-bailing, self-righting surfboat. For more than an hour the 75-year-old man maneuvered the boat through the boisterous sea. He was pleased with the performance of the boat and the crew. Upon grounding the boat he sprang onto the wet sand, glanced at the sea and stated, "The tide is ebbing" and then fell dead on the beach from a heart attack.

Joshua was buried with a lifeboat for a coffin. A second lifeboat made of flowers was placed on his grave. His tombstone bears the Massachusetts Humane Society seal and a Biblical inscription from John 15:13, "Greater love hath no man than this — that a man lay down his life for his friends."[54] The superintendent of the U.S. Life–Saving Service, Sumner Increase Kimball, said of him:

Here and there may be found men in all walks of life who neither wonder or care how much or how little the world thinks of them. They pursue life's pathway, doing their appointed tasks without ostentation, loving their work for the work's sake, content to live and do in the present rather than look for the uncertain rewards of the future. To them notoriety, distinction, or even fame, acts neither as a spur nor a check to endeavor, yet they are really among the foremost of those who do the world's work. Joshua James was one of these.[1]

Despite his frugal habits Joshua James was practically destitute at the time of his death leaving his invalid wife and children with insufficient support.[55][I] A grateful public did not forget Joshua James' lifelong efforts, and $3,733 was raised and given to Mrs. Louisa James.[56][J]

Captain James is buried in the Hull Village Cemetery in his hometown of Hull, Massachusetts. In addition to his tombstone, there is a monument to him in Hull.

Legacy

James is honored every year at his grave-site on May 23, Joshua James Day, by the Hull Life–Saving Museum at the former Point Allerton Lifesaving Station. His house built in 1850 still stands in Hull, Massachusetts and is marked as having been his home.[57] The Point Allerton station also still stands, but is no longer in use.

In 2003, the Coast Guard created the Joshua James Ancient Keeper Award to honor the Coast Guard personnel with the most seniority in rescue work and the highest record of achievement.[58]

USCGC James (WMSL-754), the fifth National Security Cutter, was named in honor of his life and dedication to saving lives.[59] The cutter's sponsor is James' great great niece, Charlene Benoit. She is the great grand daughter of Joshua James', brother Samuel James.[60]

There is a small memorial park in honor of Captain James in Hull, Massachusetts.

Captain James' Gold Lifesaving Medal is in the collection of the United States Coast Guard Museum at the Coast Guard Academy in New London, Connecticut.

Awards and decorations

United States Government

Massachusetts Humane Society awards

- Bronze Lifesaving Medal from the Massachusetts Humane Society for the rescue of the crews of the Delaware and L'Essai on Toddy Rocks on April 1, 1850.

- Certificate to Joshua James for his persevering efforts in rescuing the officers and crew of Ship Delaware, wrecked on Toddy Rocks, March 2, 1857.

- Special Silver Lifesaving Medal: 1886 from the Massachusetts Humane Society for, "brave and faithful service of more than 40 years". During this time he assisted in saving over 100 lives.

- Gold Lifesaving Medal from the Massachusetts Humane Society for the rescue of 29 persons from five different vessels during the period of November 25 through 26th 1888.

- Silver Lifesaving Medal from the Massachusetts Humane Society for the rescue of the crew from the schooner Ulrica on December 16, 1896.

Personal life

In 1859, when he was 32, James married 16-year-old Louisa Francesca Lucihe of Hull. Six of their ten children reached adulthood. Three girls and one boy died in infancy or childhood. Their surviving son, Osceola James born in 1865, became a sailor and master of the steamers Myles Standish and Rose Standish. Osceola was captain of the Hull volunteers and stations of the Massachusetts Humane Society, 1889-1928. He also received the Gold Lifesaving Medal of the U. S. Government and achieved an exceptional record of saving lives from imperiled vessels in Boston Harbor.

Children of Joshua James and Louisa Francesca Lucihe, all born in Hull

- Louisa Zulette (James) Pope (1859-1945)

- Jesse Gazella (1861-1863)

- Peter Lucihe (1863-1864)

- Osceola Ferdinand (1865-1928)

- Edith Gertrude (James) Galiano (1868-1941)

- Bertha Coletta (1870-1962)

- Estelle F. (1873-1878) and Roselle Francesca (1873-1959) - Twins.

- Genevieve Eudola (1879-1955)

- Winona Lucihe (1886-1895)

See also

- United States Life-Saving Service

- United States Lighthouse Service

- United States Coast Guard

- Point Allerton Lifesaving Station

- Pea Island Life-Saving Station

- Port Orford Lifeboat Station Museum

- Sleeping Bear Point Coast Guard Station Maritime Museum

- Chicamacomico Life–Saving Station

- Marcus Hanna (lighthouse keeper)

- Ida Lewis (lighthouse keeper)

- Dunbar Davis

- Portland Gale

- 1888 Atlantic hurricane season

Notes

- Footnotes

- ^ A woman's name of Hebrew origin meaning "my delight is in her".[62]

- ^ It was a common practice to light a bonfire close to any shipwreck that could not be rescued immediately. This was done to let the surfmen have enough light to see the shipwreck, help keep the watching surfman warm, and let the survivors of the shipwreck know that they had not been abandoned.

- ^ The station's surfboat was destroyed by a huge wave during the rescue. Joshua James was in the boats on all five trips, Osceola James, Alonzo L. Mitchell, John L. Mitchell, and Louis F. Galiano were in four of the five boat crews, and the eighteen others in trips of lesser number. It is also noteworthy that four members of the James family, four members of the Galiano family, and ten of the Mitchell family were members of the crew.[6]

- ^ The Nantasket was built by Joshua's brother Samuel. It was a very large surfboat specially built for the sea and surf conditions around Hull; its design and construction were untested.[30]

- ^ After Joshua James transferred to the U.S Life–Saving Service, his son Osceola succeeded him as the Massachusetts Humane Society Keeper for Hull until 1928.[63]

- ^ While a rescue was in progress, the wives of surfman would gather at the station, stoke a roaring fire in the stove, set out blankets and dry clothing, and prepare hot beverages. When the survivors and rescuers arrived, the women would then tend to them by treating any injuries and hypothermia. Without the action of the wives, shipwrecked sailors who survived the initial rescue and their rescuers could have died from untreated hypothermia or other injuries.[64]

- ^

- ^ In theory a person could remain with the U.S. Life–Saving Service forever, as long as they passed the annual physical.[55]

- ^ In 1882 a limited compensation was put into force whereby a widow would receive one year's pay if a lifesaver was killed in the line of duty.[55]

- ^ Sumner Increase Kimball had lobbied Congress unsuccessfully from 1876 to 1914 to provide a pension for the Service. The lack of a pension was unfair to those who served in all kinds of weather and with a very real chance of serious injury or death only to be dismissed or forced to resign due to injury or infirmities of advancing age.[67]

- Citations

- "Captain Joshua James, USLSS", Personnel, U.S. Coast Guard Historian's Office

- Kimball, Spencer, Joshua James, Life–Saver, American Unitarian Association, 1909, Boston, MA, at 7, 8, 12, 15, 17-19, 23, 25, 52, and 53.

- http://site.mawebcenters.com/hulllifesavingmuseum1/index.html

- Joshua James sworn statement of January 5, 1889.

- New York Times, November 27, 1888

- http://www.uscg.mil/history/awards/25NOV1888.asp%5B%5D

- New York Times, November 27, 1888

- Annual Reports of the United States Life–Saving Service 1889 Pg.63

- Shanks, Ralph and York, Wick, pp 47–50

- Galluzo, p 127

- Galluzo, p 120, pp 128–130

- Galluzo, p 14

- Galluzo, p 15

- Boston Globe December 17, 1896.

- U.S. Lifesaving Station Point Allerton, Wreck Report for January 8, 1897.

- U.S. Lifesaving Station Point Allerton Log for December 16, 17, 18, 1891.

- Robert W. Haley (Wreck & Rescue - Volume 1, Number 4)Brave Men of Hull

- The Boston Daily Advertiser, December 18 and 20, 1841

- Patriot, December 18 and 20, 1841

- Smith, Jr., Storms and Shipwrecks In Boston Bay and the record of The Life Savers of Hull, Privately Printed, Boston, 1918. Pg 22

- The Boston Daily Advertiser, October 14, 1844

- Patriot, October 14, 1844

- Smith, Jr., Storms and Shipwrecks In Boston Bay and the record of The Life Savers of Hull, Privately Printed, Boston, 1918. Pg 27

- Smith, Jr., Storms and Shipwrecks In Boston Bay and the record of The Life Savers of Hull, Privately Printed, Boston, 1918. Pg 34

- New York Times, December 3, 1885

- New York Times article, November 27, 1888

- Smith, Jr., Storms and Shipwrecks In Boston Bay and the record of The Life Savers of Hull, Privately Printed, Boston, 1918. Pg 40

- United States Live-Saving Service Annual Report 1889, Pg 62.

- New York Times Pg.8, November 29, 1888

- Smith, Jr., Storms and Shipwrecks In Boston Bay and the record of The Life Savers of Hull, Privately Printed, Boston, 1918. Pg 39

- United States Live-Saving Service Annual Report 1889, Pg 62

- Kimball, Spencer, Joshua James, Life–Saver, American Unitarian Association, 1909, Boston, Massachusetts, Pg 39, 40.

- U.S. Lifesaving Station Point Allerton Log for November 6, 1891

- U.S. Lifesaving Station Point Allerton Log, August 26, 1892

- U.S. Lifesaving Station Point Allerton, Wreck Report for August 26, 1892

- U.S. Lifesaving Station Point Allerton Wreck Report, February 19, 1893

- U.S. Lifesaving Station Point Allerton Log entry, February 20, 1893

- U.S. Lifesaving Station Point Allerton Log, April 8, 1894

- Boston Globe, Page 1 April 9, 1894

- U.S. Lifesaving Station Point Allerton, Log entry for December 16, 17, 18 and January 1896

- .S. Lifesaving Station Point Allerton, Wreck Report January 8, 1897

- The Boston Post, December 17, 1896.

- U.S. Lifesaving Station Point Allerton, Wreck Report for December 16, 1898

- U.S. Lifesaving Station Point Allerton, Wreck Report for November 27, 1898

- Boston Globe, Pg. 2, December 4, 1898

- U.S. Lifesaving Station Point Allerton Log, December 1, 1898

- U.S. Lifesaving Station Point Allerton, Wreck Report for December 22, 1900

- U.S. Lifesaving Station Point Allerton Log, February 25, 1900

- U.S. Lifesaving Station Point Allerton, Wreck Report for February 25, 1900

- U.S. Lifesaving Station Point Allerton Log entry February 25, 1900

- U.S. Lifesaving Station Point Allerton, Wreck Report for October 7, 1901

- Smith, Jr., Storms and Shipwrecks In Boston Bay and the record of The Life Savers of Hull, Privately Printed, Boston, 1918. Pg 38

- Kimball. Joshua James: Life–Saver. Boston, Massachusetts: American Unitarian Association. p. 39.

- https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=John+15%3A13&version=KJV

- Noble, p 56

- United States Life–Saving Service Annual Report 1902, Pg 14

- U.S. Coast Guard site, with photographs of house (accessed January 13, 2008)

-

"Garde Arts Center to host 'Finest Hours' screening, panel discussion". Norwich Bulletin. 2016-02-29. Archived from the original on 2016-03-01. Retrieved 2016-02-29.

The panel discussion will be moderated by Harriet Jones, business editor of WNPR Connecticut Public Radio, and will include Tony Falcone, artist and personal friend of Bernard Webber; Jack Downey, U.S. Coast Guard retired and first recipient of the Joshua James Ancient Keeper award; Lt. Daniel Tavernier, commanding officer, U.S. Coast Guard Station New London; and Cmdr. Andrew Ely, chief of response, U.S. Coast Guard Sector Long Island Sound.

- "Acquisition Update: Keel Authenticated for the Fifth National Security Cutter". US Coast Guard Acquisition. 2013-05-17. Retrieved 2014-05-09.

- "Keel Authenticated for Ingalls Shipbuilding's Fifth National Security Cutter". Huntington Ingalls Industries, Inc. 2013-05-17. Retrieved 2014-05-09.

- http://www.uscg.mil/history/awards/GoldLSM/25NOV1888.asp

- http://www.thinkbabynames.com/meaning/0/Hepzibah

- Noble, p 201

- Shanks and York, pp 125–128

- Means, The American Neptune, Vol. XXXVII, No. 2, 1977. Peabody Museum, Salem, MA, 1977

- Galluzo, p 201

- Noble, pp 56–57

- References used

- "Captain Joshua James, USLSS". Personnel. U.S. Coast Guard Historian's Office. Retrieved 23 April 2014.

- Carlson, A.E. "Joshua James — Lifesaver." Coast Guard Public Information Division pamphlet, 1959.

- Galluzo, John J. (2007). They Had To Go Out ... True Stories Of America's Coastal Life–Savers From The Pages Of "Wreck & Rescue Journal". Avery Color Studio, Inc., Gwinn, Michigan. ISBN 978-1-892384-39-3.

- Joshua James sworn statement January 5, 1889.

- Kimball, "Joshua James, Life–Saver", American Unitarian Association, Boston, Massachusetts, 1909

- Means, The American Neptune, Vol. XXXVII, No. 2, 1977. Peabody Museum, Salem, Massachusetts, 1977

- Means, Dennis R. SAND ENOUGH The Legacy of Capt. Joshua James of Hull, Massachusetts, The Means Library, Weymouth, Massachusetts, 2012, 2013, ISBN 978-0-615-74935-8

- Noble, Dennis L. (1994). That Others Might Live: The U.S. Life–Saving Service, 1878–1915. Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, Maryland. ISBN 978-1-55750-627-6.

- Shanks, Ralph; Wick York (1996). The U.S. Life–Saving Service, Heroes, Rescues and Architecture of the Early Coast Guard. Petaluma, California: Costaño Books. ISBN 978-0-930268-16-9.

- Smith, Jr., Storms and Shipwrecks In Boston Bay and the record of The Life–Savers of Hull, Privately Printed, Boston, 1918.

Further reading

- Kimball, Sumner (1909). "Joshua James: Life–Saver". Boston: American Unitarian Association. Retrieved May 1, 2014.

- Furlong, Lawrence (1800). "The American Coast Pilot: Third Edition" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on August 10, 2004. Retrieved August 10, 2004.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Joshua James. |

- Hull Life–Saving Museum (accessed May 9, 2011)

- U.S. Coast Guard Historian (accessed April 17, 2011)

- Boston Shipwrecks

- Massachusetts Humane Society

- Nautical Chart 13270, Boston Harbor

- Boston Harbor and Approaches(accessed June 21, 2011)

- Coast Pilot 1 Chart 13270 - (Chapter 11)(accessed April 21, 2011)

- U.S. Life–Saving Service Heritage Association

- Joshua James at Find a Grave