Jones-Miller Bison Kill Site

The Jones-Miller Bison Kill Site, located in northeast Colorado, was a Paleo-Indian site where Bison antiquus were killed using a game drive system and butchered. Hell Gap complex bones and tools artifacts at the site are carbon dated from about ca. 8000-8050 BC.[1][2][nb 1]

Geography

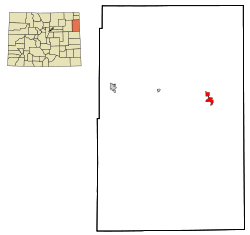

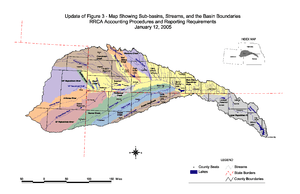

The Jones-Miller site is located in Yuma County, Colorado, 10 miles from the town of Laird in the Republican River basin.[3] The grassland site is located at a 18 inches (46 cm) deep draw that drains into an Arikaree River tributary.[4]

History

Background

Within the Denver Basin, prehistoric time periods are traditionally identified as: Paleo-Indian, Archaic and Ceramic (Woodland) periods.[5] The Denver basin is a geological definition of a portion of the Colorado Piedmont from Colorado Springs to Wyoming and west to Kansas and Nebraska. The Palmer Divide, with elevations from 6,000 to 7,500, is a subsection of that area that separates the South Platte River watershed from that of the Arkansas River.[6] It runs perpendicular to the Rocky Mountains and divides the Denver metropolitan area from the southern Pikes Peak area.[7]

The period immediately preceding the first humans coming into Colorado was the Ice Age Summer of about 16,000 years ago. Large mammals, such as the mastodon, mammoth, camelops, giant sloths, cheetah, bison antiquus and horses roamed the land. There were a few Paleo-Indian cultures, distinctive by the size of the tools they used and the animals they hunted. People in the first Paleo-Indian period, the Clovis complex period, had large tools to hunt the megafauna animals.[8]

By 11,000 years ago (9,000 BC), the climate warmed and lakes and savannas receded. The land became drier, food became less abundant, and as a result of the giant animals became extinct. Receding and melting glaciers created the Plum and Monument Creeks, created the Castle Rock mesas and unburied the Rocky Mountains.[8] People adapted by hunting smaller mammals and gathering wild plants to supplement their diet.[9] A new cultural complex was born, the Folsom tradition, with smaller projectile points to hunt smaller animals.[8][10] Aside from hunting smaller mammals, people adapted by gathering wild plants to supplement their diet.[9]

The Lindenmeier Site, the largest known Paleo-Indian Folsom site,[11] contained artifacts of the Paleo-Indians who lived and hunted in the present Fort Collins area approximately 11,000 years ago. Some of the artifacts are identified from people of the Folsom tradition, named for the Folsom Site in New Mexico, and identified as such by the Folsom points used for hunting the large, now extinct Bison antiquus. They likely also gathered food in the area, such as seeds, nuts and seasonal fruits. They were nomadic people, following the bison herds, and camping many places each year.[12][13]

Paleo-Indian Folsom site

Robert Jones, Jr., a rancher in the Wray, Colorado area, found bones and projectile points near his home in 1972. Jack Miller, a local anthropologist, performed a test site excavation and found bones and Paleo-Indian artifacts. Dennis Stanford, an archaeologist at the Smithsonian Institution, was contacted and a full-scale excavation of the Jones Miller site was performed between 1973 and 1978[14] of what is primarily a bison kill site. Waldo Rudolph Wedel said in 1986 that it was the "most carefully studied bison kill" site.[3]

Archaeologists learned how early native people may have hunted large prey from the artifacts at the 98 by 66 feet (30 by 20 m) Jones-Miller site. Remains of 300 bison were found in an arroyo, or draw, above the Arikaree River basin. It was believed that the bison were strategically driven into an area difficult for the bison to traverse and easier to kill on three occasions. Because many of the animals were nursing calves, it is estimated that the kills occurred in late fall or winter.[2][14][15][nb 2] The bones from the bison kill were piled into many stacks, indicating that there were several butcher sites.[2]

Artifacts found at the site include Hell Gap complex projectile points and flakes, knives, scrapers and tools made of bone.[2] While there is little evidence to determine the extent to which Paleo-Indians practiced religion, artifacts grouped together at the Jones-Miller site are like that of historic northern Plains people's medicine post ceremony where, among the bison bones were placed a projectile point, dog remains and an antler flute.[15] The practice is similar to that of the Cree and Assiniboine people. The site is dated at 10,020 +/- 320 years before present, or about 8000 BC. It is the only Hell Gap (Wyoming) site in Colorado.[16]

Collection

The collection of artifacts from the Smithsonian Institution's excavation in the 1970s was donated to the Denver Museum of Nature and Science in 1997. The collection, called the "Jones-Miller Hell Gap Bison Kill Site Collection," contains bison bones, projectile points and stone tools.[17]

Notes

- Kipfer states that the site is dated about 8000 BC; Gibbon and Ames state the site is carbon dated to about 8050 BC

- The Manitoba Archaeological Society estimated the event occurred in the fall; Gibbon and Ames - and Cassells - described it as a winter kill.

References

- Kipfer, p. 266.

- Gibbon, Ames, p. 401.

- Wedel, p. 65.

- Gibbon, Ames, pp. 400-401.

- Nelson, pp. 7, 65.

- Nelson, pp. 7, 21, 33.

- Nelson, Laubach.

- Waldman, 5.

- Griffin-Pierce, p. 130.

- Johnson, p. 30.

- Gantt, 1.

- Buccholtz, Chapter 1.

- Local History Archive.

- Cassells, p. 79.

- Folsom Traditions 9,000 - 8,000 BC.

- Cassells, pp. 79-80

- Colwell, Nash, Holen, PT75.

Bibliography

- Buccholtz, C.W. (1997) [1983] Rocky Mountain National Park: Tales, Trails and Tribes. University Press of Colorado. Retrieved 9-19-2011.

- Cassells, E. Steve. (1997) [1983] The Archaeology of Colorado. Boulder: Johnson Press. ISBN 1-55566-193-9.

- Colwell, Chip; Nash, Stephen E.; Holen, Steven R. (2010) Crossroads of Culture: Anthropology Collections of the Denver Museum of Nature & Science. Boulder: University Press of Colorado.

- Folsom Traditions 9,000 - 8,000 BC. Manitoba Archaeological Society. 1998. Retrieved 9-28-2011.

- Gantt, Erik M. The Claude C. and A. Lynn Coffin Lindenmeier Collection. Colorado State University. Retrieved 9-19-2011.

- Gibbon, Guy E.; Ames, Kenneth M. Archaeology of Prehistoric Native America: An Encyclopedia. 1998. ISBN 0-8153-0725-X.

- Griffin-Pierce, Trudy. (2010). The Columbia Guide to American Indians of the Southwest. New York:Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-12790-5.

- Johnson, Kirk R.; Raynolds, Robert G. (2006). "Ancient Denvers: Scenes from the Past 300 Million Years of the Colorado Front Range". Fulcrum Publishing for Denver Museum of Nature and Science. ISBN 1-55591-554-X.

- Kipfer, Barbara Ann. (2000). Encyclopedic Dictionary of Archaeology. New York:Plenum Publisher. ISBN 0-306-46158-7.

- Local History Archive: A Tour of the Lindenmeier/Folsom Site (partial transcription of September 1, 1980 recorded talk) Fort Collins Public Library. Retrieved 10-15-2007.

- Nelson, Michael; Laubach, Tony. Where Is That? Explaining The Different Regions of Colorado. The Denver Channel. October 27, 2009. Retrieved 9-28-2011.

- Nelson, Sarah M. (2008). Denver: An Archaeological History. Boulder, CO: University Press of Colorado. ISBN 978-0-87081-935-3.

- Wedel, Waldo Rudolph. (1986) Central Plains Prehistory: Holocene Environments and Culture Change in the Republican River Basin. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-4729-X.

Further reading

- Davis, L.; Wilson, M. (editors). (1978) Bison Procurement and Utilization: A Symposium. Memoir no. 14. Lincoln: Plains Anthropologist.

- Frison, G.C. (1971). The Buffalo Pound in Northwestern Plains Prehistory: Cite 48CA302. American Antiquity. 36:77-91.

- Frison, G.C. (1991). Prehistoric Hunters of the High Plains. 2nd. edition. San Diego: Academic Press.

- Stanford, D.J. (1974). Preliminary Report on the Excavation of the Jones-Miller Hell Gap Site, Yuma, Colorado. Southwestern Lore. 40(3-4):29-36.

- Stanford, D.J. (1978). The Jones-Miller Site: An Example of Hell Gap Bison Procurement Strategy. In Bison Procurement and Utilization: A Symposium, edited by L. Davis and M. Wilson, pp. 90–97. Memoir no. 14. Lincoln: Plains Anthropologist.