Joint Expeditionary Base Fort Story

Joint Expeditionary Base-Fort Story, commonly called simply Fort Story is a sub-installation of Joint Expeditionary Base Little Creek–Fort Story, which is operated by the United States Navy. Located in the independent city of Virginia Beach, Virginia at Cape Henry at the entrance of the Chesapeake Bay,[1] it offers a unique combination of features including dunes, beaches, sand, surf, deep-water anchorage, variable tide conditions, maritime forest and open land. The base is the prime location and training environment for both Army amphibious operations and Joint Logistics-Over-the-Shore (LOTS) training events.

| Fort Story | |

|---|---|

| Part of Joint Expeditionary Base Little Creek-Fort Story | |

| Virginia Beach, Virginia | |

Command Logo | |

| Coordinates | 36.9273°N 76.0164°W |

| Type | Army Base |

| Site information | |

| Controlled by | |

| Site history | |

| In use | 1914–present |

The base includes 1,451 acres (5.9 km²) of sandy trails, cypress swamps, maritime forest, grassy dunes and soft and hard sand beaches. The western beaches are wide, gently sloped and washed by the waters of the Chesapeake Bay. Eastern beaches are exposed to the rougher waters of the Atlantic surf.

History

Installation history

- World War I

Fort Story became a military installation in 1914 when the Virginia General Assembly gave the land to the U.S. Government "to erect fortifications and for other military purposes". The base was named for Major General John Patten Story (1841-1915), a noted coast artilleryman of his day. During World War I, Fort Story was integrated into the Coast Defenses of Chesapeake Bay, which also included Fort Monroe (the headquarters)[2] and Fort Wool. Fort Story remained a Coast Artillery Corps post until after World War II. The initial armament was modest. Two "emergency" batteries of rapid-fire guns were emplaced at Fort Story with weapons taken from other forts. Battery A had two 6-inch (152 mm) M1900 guns moved from Fort Monroe, and Battery B had two 5-inch (127 mm) M1900 guns moved from Fort Andrews near Boston. In 1919 the 6-inch guns were returned to Fort Monroe, while the 5-inch guns were removed from service as part of a general retirement of 5-inch guns from the Coast Artillery.[3][4]

- Between the wars

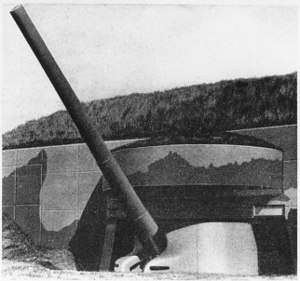

After World War I, Battery Pennington, consisting of four 16-inch (406 mm) M1920 howitzers, was emplaced at Fort Story in 1922, along with a three-gun antiaircraft battery of 3-inch (76 mm) M1917 guns. The 16-inch howitzer had a barrel length of 25 calibers; the contemporary 16-inch gun M1919 had a 50-caliber barrel. With the improved weapon location at Fort Story and a range advantage over Fort Monroe's 12-inch guns of 24,500 yards (22,400 m) versus 18,400 yards (16,800 m), the 16-inch weapons could engage attacking warships long before they could come within range of Fort Monroe.[3][5] Fort Story was the only location to receive these howitzers, though a few other harbor defenses received the longer 16-inch guns in the 1920s.[6] At Fort Story, the new weapons were not accompanied by smaller-caliber rapid-fire guns until 1942.[3] In 1924, the coast defense command was designated a Harbor Defense Command and entered a period of post-war inactivity which lasted until the beginning of World War II. Following regimentation of the Coast Artillery Corps, the Harbor Defenses of Chesapeake Bay were garrisoned by the 12th Coast Artillery Regiment of the regular army,[7] with the 246th Coast Artillery Regiment as the Virginia National Guard component.[8] In 1932 the 12th Coast Artillery was effectively redesignated as the 2nd Coast Artillery, continuing as the garrison of Chesapeake Bay.[9] In May 1928, the first battle practice of units of the coast artillery was held since the end of World War I. A battalion of 8-inch (203 mm) railway guns fired at "hostile" ships 16,000 yards out to sea; the 1st Battalion of the 12th Coast Artillery and the 52nd Coast Artillery (Railway) participated.[10]

A 1922 map shows positions for a 12-inch (305 mm) Batignolles railway gun and a 14-inch (356 mm) M1918 railway gun; these were probably for trials rather than operational weapons. The Batignolles mount was a French design used with 12-inch guns to produce US-made railway artillery during World War I.[11] The 14-inch gun M1918 was a developmental weapon that did not see active service;[12] the 14-inch M1920 railway gun was eventually deployed instead, though not at Fort Story.[13]

- World War II

In 1941, prior to the United States entering World War II, more land was acquired at Fort Story. Following the American entry into World War II two four-gun batteries of 155 mm (6.1 in) guns were deployed at Fort Story; circular concrete "Panama mounts" were built to improve their firing positions. These were a stopgap until three 6-inch (152 mm) gun batteries were completed at the fort in 1943.[3] In addition to the 16-inch (406 mm) howitzers, four 16-inch ex-Navy Mark II guns were installed at Fort Story during World War II as Battery Ketcham (originally Battery 120) and Battery 121. These batteries were casemated against air attack; the howitzers also received gunhouses for splinter protection. The 16-inch howitzers were split into Battery Pennington and Battery Walke for fire control purposes; they had previously been Pennington A and B.[14] These guns, along with matching batteries located at Fort John Custis on Cape Charles and batteries at Fort Monroe on Old Point Comfort, were used to guard the entrance to Chesapeake Bay against an attack by hostile naval forces.[15]

The batteries that existed during World War II at Fort Story included:[3][15]

| Name | No. of guns | Gun type | Carriage type | Years active |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ketcham (Battery 120) | 2 | 16-inch (406 mm) Navy MkIIMI gun | barbette M4 | 1943–1948 |

| Battery 121 | 2 | 16-inch (406 mm) Navy MkIIMI gun | barbette M4 | 1943–1948 |

| Pennington | 2 | 16-inch (406 mm) howitzer M1920 | barbette M1920 | 1922–1947 |

| Walke | 2 | 16-inch (406 mm) howitzer M1920 | barbette M1920 | 1922–1947 |

| Worcester (Battery 224) | 2 | 6-inch (152 mm) gun M1900 | pedestal M1900 | 1941–1947 |

| Cramer (Battery 225) | 2 | 6-inch (152 mm) gun M1903 | shielded barbette T2-M2 | 1943–1948 |

| Battery 226 | 2 | 6-inch (152 mm) gun T2-M1 | shielded barbette M4 | 1943–1949 |

| Anti-Motor Torpedo Boat (AMTB) 19/Examination battery | 2 | 3-inch (76 mm) gun M1902 | pedestal M1902 | 1942–1945 |

| AMTB 21 | 4 | 90 mm (3.54 in) gun | two fixed T3/M3, two mobile | 1943–1945 |

| AMTB 22 | 4 | 90 mm (3.54 in) gun | two fixed T3/M3, two mobile | 1943–1950 |

| Battery 155 (1) | 4 | 155 mm (6.1 in) gun | Panama mounts | 1942–194? |

| Battery 155 (2) | 4 | 155 mm (6.1 in) gun | Panama mounts | 1942–194? |

In 1944, Fort Story began to transition from a heavily fortified coast artillery garrison to a convalescent hospital for returning veterans. By the time of its closing March 15, 1946, the hospital had accommodated more than 13,472 patients.

- Post World War II

In 1946, after World War II, the first amphibious training at Fort Story began with the arrival of the 458th Amphibious Truck Company and Army DUKWS. Fort Story was officially transferred to the Transportation Training Command, Fort Eustis, and designated a Transportation Corps installation for use in training amphibious and terminal units in the conduct of Logistics-Over-The-Shore operations.

Following World War II, coast defense guns and the Coast Artillery Corps were considered obsolete, and Fort Story's guns were scrapped by 1949.[3]

Fort Story was declared a permanent installation on December 5, 1961.

Historic features

Joint Expeditionary Base Fort Story has three historic sites. The Cape Henry Memorial Cross marks the location where the Jamestown Settlers first landed in 1607. The Old Cape Henry Light was the first lighthouse authorized and built by the Federal Government. At the Battle of the Virginia Capes Monument, there is a statue of French Admiral François Joseph Paul, comte de Grasse to commemorate the famous sea battle on September 5, 1781 which prevented the British from reaching Yorktown during the American Revolutionary War.

Also of historical interest, the new Cape Henry Lighthouse was completed in 1881 and is still maintained by the US Coast Guard as an active coastal beacon. The passenger station built in 1902 and served by the original Norfolk Southern Railway was restored late in the 20th century and is used as an educational facility by the Army.

The coast defense weapons were removed in 1948 and their large casemated gun emplacements and former ammunition bunkers are currently used for storage.

An Army Nike missile battery was located at Fort Story from 1958 to 1974 (sites N-25/N-29).[16]

At 7.35pm on Saturday 30 November 2019, a Master-at-arms was killed at Gate 8, a 24 hour entry, when a civilian pickup truck was driven into a security vehicle at the gate. Both victims were taken to Sentara Virginia Beach General Hospital, where the sailor died of his injuries.[17]

Current utilization

Command structure

As a result of a 2005 Base Realignment and Closure recommendation, Fort Story operations were transferred to the United States Navy. On October 1, 2009, Fort Story and Naval Amphibious Base Little Creek merged, and Fort Story officially became Joint Expeditionary Base Little Creek Fort Story.[18][19]

Tenants

The following organizations were present at Joint Expeditionary Base Fort Story in 2009:

- AAFES

- 11th Transportation Battalion

- Army Reserve Center

- U.S. Army School of Music

- Directorate of Training and Doctrine

- FORSCOM Logistics Training Cluster, Saltwater Annex

- U.S. Marine Corps Security Cooperation Group

- Naval Special Warfare Group 2 Ranges

- Navy Explosive Ordnance Disposal Training and Evaluation Unit Two

- Navy Explosive Ordnance Disposal Expiditionary Support Unit Two

- Naval Undersea Warfare Center

- Shipboard Electronic Systems Evaluation Facility

- NATO Communication Logistical Activity

See also

References

- Area map Archived 2009-04-14 at the Wayback Machine

- Stanton, Shelby L. (1991). World War II Order of Battle. Galahad Books. p. 478. ISBN 0-88365-775-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fort Story at FortWiki.com

- Fort Monroe at FortWiki.com

- Berhow, Mark A., Ed. (2015). American Seacoast Defenses, A Reference Guide, Third Edition. McLean, Virginia: CDSG Press. p. 61. ISBN 978-0-9748167-3-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Berhow 2015, pp. 227–228.

- Gaines, William C., Coast Artillery Organizational History, Regular Army regiments, 1917-1950, Coast Defense Journal, vol. 23, issue 2, p. 10

- National Guard Coast Artillery regiment histories at the Coast Defense Study Group

- Gaines regular army, p. 5

- Staff, "Coast Defense Guns Boom Again In First Mock Battle Since War", San Bernardino Daily Sun, San Bernardino, California, Saturday 2 June 1928, Volume LXII, Number 94, page 3.

- Miller, H. W., LTC, USA (1921), Railway Artillery, Vols. I and II, vol. I, pp. 197–225

- Miller vol. I, pp. 367–380

- Berhow 2015, pp. 216, 223.

- Battery Pennington at FortWiki.com

- Harbor Defenses of Chesapeake Bay at cdsg.org

- "Hampton Roads Area - Fort Story". American Forts Network. Retrieved 30 June 2020.

- Navy: Master-At-Arms killed by gate runner, Courtney Mabeus, Navy Times, 2019-12-01

- JEBLC Home Page

- JEBLC History