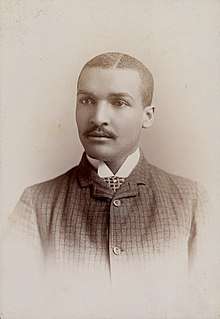

John Wesley Gilbert

John Wesley Gilbert (July 6, 1863[1] – November 18, 1923) was an American archaeologist, educator, and Methodist missionary to the Congo. Gilbert was the first graduate of Paine College, the first African-American professor of that school, and the first African-American to receive an advanced degree from Brown University.[2][3]

John Wesley Gilbert | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | July 6, 1863 |

| Died | November 19, 1923 |

| Education | A.B, A.M, Brown University |

| Occupation | Professor at Paine College, President of Miles College, Archaeologist |

| Spouse(s) | Osceola Pleasant Gilbert (married 1889) |

| Children | 4 |

Early life

Gilbert was born to slaves in Hephzibah, Georgia, though he grew up in nearby Augusta. He was named after John Wesley, the founder of Methodism.[4] Until he left Georgia, Gilbert "spent half the year on the farm and the other half in the public schools of the city of Augusta."[5] After finishing public school, Gilbert enrolled in the Augusta Institute (later the Atlanta Baptist Seminary, a predecessor of Morehouse College).[1] In 1884, he enrolled in the newly opened Paine Institute (later known as Paine College), which had been established as an "interracial" venture between the Methodist Episcopal Church, South and the Colored Methodist Episcopal Church.[6] In 1886, he was given financial assistance to transfer into the junior class of Brown University. There, he was among the first ten black students to attend the school and among the forty African-Americans to graduate from any northern university between 1885 and 1889.[1]

Gilbert received his bachelor's degree from Brown in 1888. He then moved back to Georgia, where in 1889 he married Osceola Pleasant, a graduate of Fisk University and the Paine Institute.[1]

Work in Greece

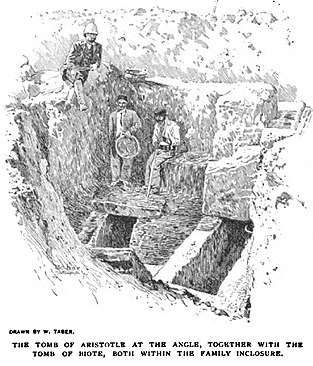

While at Brown, Gilbert received a scholarship to attend the American School of Classical Studies in Athens, Greece -- at the encouragement of Albert Harkness, a prominent classicist involved in the school's foundation.[7][8] He was the first African American to attend that school, and remained the only one to have done so through 1901.[9] During his time in the country, Gilbert was given an award for "excellence" in Greek.[9] He was there from 1890-1891 and conducted archaeological excavations on Eretria with John Pickard, producing the first map of Ancient Eretria. Their work supposedly uncovered the "tomb of Aristotle," a claim that was quickly disproven.[7]

For his work in Greece, Gilbert in 1891 became the first African-American to receive an advanced degree from Brown. He received his master's thesis on the topic of "The Demes of Attica" (now unfortunately lost). In 1897, Gilbert was honored with election to the American Philological Association.[7]

Work as an educator

In 1891, Gilbert returned to Augusta, Georgia and began to teach Greek, French, German, Latin, and Hebrew at his former school, Paine College.[1] His appointment caused an uproar, since he was the first black faculty member at Paine. Other faculty decried "the evil" of this "revolutionary measure."[10] His appointment was also important because of his classical education: as a Paine professor later put it, "this was to be a college, and to be a college, you had to teach Greek and Latin."[4] He was remembered at Paine most of all as an "an exacting teacher" who "would not tolerate weak excuses," since "he knew from personal experience that only diligence and plain hard work produced scholars."[10] He is supposed to have said: "If you would like to realize your own importance put your finger in a bowl of water, take it out, and look at the hole."[10] Students later recalled that

the exacting scholar corrected a startled student for his use of a Greek verb. The student, abashed, protested, “But that’s exactly the way it is in the textbook.” Gilbert, they report, replied, "Then the textbook is wrong. Bring it here." The textbook was wrong as Gilbert immediately pointed out to the publisher. It was changed in the next edition.[10]

In 1913, Gilbert was appointed the president of Miles College. He served in that post for one year before returning to Paine College.[1]

Work as a missionary

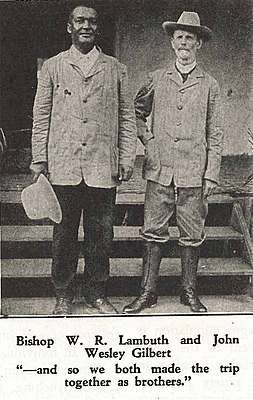

In 1911 and 1912, Gilbert undertook a mission to the Belgian Congo with Walter Russell Lambuth, a (white) bishop of the Methodist Episcopal Church, South. Gilbert believed that "Africa needs thousands of teachers, graduates of Atlanta, Fisk, Moorehouse, Paine, and similar institutions; for, besides possessing by nature the race instinct, they are better suited physically for work in Africa than their white brethren."[11] Similarly, Lambuth argued that southern Methodists were suited to successfully evangelize Africa: "We are born and brought up with black men. They understand us, and we understand them. We understand their good qualities and their bad qualities."[12] Lambuth and Gilbert cooperated well; Lambuth praised Gilbert's language skills, writing that his translations were "so well done that the Colonial Minister, upon my subsequent visit to Brussels, inquired who wrote the letters, and remarked that they were the most correct and elegantly expressed among those received at his office from one who was not a native of either France or Belgium."[13] Gilbert's passion for languages and sense of the “Southern Negro’s debt and responsibility to Africa” even led him to compile a vocabulary and grammar for Tetela, a language spoken in the area of their work.

Gilbert and Lambuth successfully established a church and school in the village of Wembo-Nyama.[14] This school would later educate Patrice Lumumba, the first prime minister of the Democratic Republic of the Congo and an icon of anticolonialism and pan-Africanism.[13] In its current form as the Patrice-Emery-Lumumba University of Wembo-Nyama, this school is supported by American Methodists to this day.[13] The mission of Gilbert and Lambuth was remembered as an exemplar of interracial partnership.[12] However, even from the beginning there were "persistent rumors that the Belgian government was not highly cordial to Gilbert’s return."[10] Rather than a joint mission of the (black) CME and (white) MECS, by the 1920s and 30s the Methodist missionaries in Wembo-Nyama were exclusively white.[4] Sylvia Jacobs argues that "probably the greatest obstacle was the Belgian government, which refused to issue permits to African Americans seeking to reside in the Belgian Congo" because of prior agitation against Belgian atrocities.[15]

Reception and legacy

Gilbert was ill by 1921 and died on 18 November 1923 in Augusta, Georgia. Soon after his death, The Spirit of John Wesley Gilbert was published as a kind of eulogy. The author outlined the "Gilbert program … in the following sentences: No two races can live together, interlarded, under the same laws, but with different race marks and proclivities, in anything like peace without a program of 'good will' and interracial understanding."[16]

Gilbert's contemporary reception and later legacy were complex. His beliefs in interracial partnership were controversial at the time. African-American newspapers and magazines -- including The Horizon, edited by W. E. B. Du Bois -- criticized his political views.[13] The Appeal wrote that Gilbert would "make the Afro-American … just as he was in the times of slavery, perfectly willing to accept the white man as massa," going on to write that "in the opinion of THE APPEAL, Rev. (?) Gilbert is a flunkey who deserves the contempt of every self-respecting Afro-American."[13] But Gilbert also had an immense positive influence as an educator and a role model, including on another prominent African American from Augusta, John Hope, the first black president of Morehouse College and one of the founding members of the Niagara Movement.[17]

Gilbert's alma mater, Paine College, dedicated a chapel in honor of him and Bishop Lambuth in 1968.[3] In 1941, the city of Augusta built a low-income housing complex across the street from Paine College.[18] In honor of Gilbert, the complex was named Gilbert Manor. The housing was closed in 2008 in order to make room for expansion of the Medical College of Georgia.[19]

References

- Lee, John W.I. Lee. "GILBERT, John Wesley". Database of Classical Scholars | Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey. Retrieved 2019-08-27.

- Mitchell, Martha (1993). "African Americans". Encyclopedia Brunoniana. Retrieved 2019-08-27.

- "Gilbert-Lambuth Memorial Chapel - Paine College". www.paine.edu. Retrieved 2019-08-27.

- Bielenberg, Aliosha (2018-03-08). "Scholar, Activist, or Religious Figure? John Wesley Gilbert's Reception and Legacy". Aliosha's Notes. Retrieved 2019-08-27.

- Culp, Daniel Wallace, ed. (1902). Twentieth century Negro literature; or, A cyclopedia of thought on the vital topics relating to the American Negro. Toronto: J. L. Nichols & Co. p. 190.

- Hildebrand, Reginald Francis. (1995). The times were strange and stirring : Methodist preachers and the crisis of emancipation. Durham: Duke University Press. ISBN 0822316277. OCLC 31708274.

- Lee, John W.I. (2017-08-01). "An African American Pioneer in Greece: John Wesley Gilbert and the American School of Classical Studies at Athens, 1890-1891". From the Archivist's Notebook. Retrieved 2019-08-27.

- Adelaide M. Cromwell, Martin Kilson, Apropos of Africa: Sentiments of Negro American Leaders on Africa from the 1800s to the 1950s, Routledge, 1969, pp 116.ISBN 0714617571, ISBN 978-0-7146-1757-2

- Henry F. Kletzing, et al. Progress of a Race, J. L. Nichols., 1903. pp. 520.

- Calhoun, Eugene Clayton (1961). Of Men who Ventured Much and Far: The Congo Quest of Dr. Gilbert and Bishop Lambuth. Atlanta, GA: Institute Press. pp. 16–17.

- Gilbert, John Wesley (1914). "The Southern Negro's Debt and Responsibility to Africa". In A. M. Trawick (ed.). The new voice in race adjustments: addresses and reports presented at the Negro Christian student conference, Atlanta, Georgia, May 14–18, 1914. New York: Student Volunteer Movement. pp. 129–133. Retrieved 2019-05-20.

- Kasongo, Michael O. (1998). "A spirit of cooperation in mission: Professor John Wesley Gilbert and bishop Walter Russell Lambuth" (PDF). Methodist History. 36 (4): 260–265.

- Brynn, Amanda; Bielenberg, Aliosha (2019-05-09). "How to Write Black Disciplinary History on Its Own Terms". eidolon. Retrieved 2019-08-27.

- "Gilbert, John Wesley (1865-1923)". Methodist Mission Bicentennial. 2018-01-02. Retrieved 2019-08-27.

- Jacobs, Sylvia M. (2002). "African Missions and the African-American Christian Churches". In Vaughn J. Walston; Robert J. Stevens (eds.). African-American experience in world mission: a call beyond community. Pasadena, CA: William Carey Library. pp. 30–47. ISBN 978-0-87808-461-6.

- Colclough, Joseph C. (1925). The spirit of John Wesley Gilbert. Nashville, TN: Cokesbury Press. pp. 29–30.

- Leroy Davis, A Clashing of the Soul, University of Georgia Press, 1998, pp 33. ISBN 0-8203-1987-2, ISBN 978-0-8203-1987-2

- Johnny Edwards "MCG plans memorial to Gilbert Manor namesake", Augusta Chronicle, January 29, 2009. Retrieved 01-29-2009.

- Stephanie Toone Neighbors now scattered about, Augusta Chronicle, January 1, 2009. Retrieved 01-28-2009