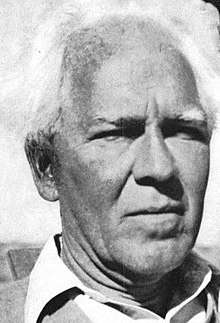

John Moynihan Tettemer

John Moynihan Tettemer (1876–1949) was the author of I Was a Monk: The Autobiography of John Tettemer, a 1951 account of his life as a Passionist monk and member of the Roman Catholic priesthood.[1][2]

John Moynihan Tettemer | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | May 16, 1876 St. Louis, Missouri, U.S. |

| Died | May 14, 1949 Los Angeles County, California, U.S. |

| Nationality | American |

| Other names | Father Ildefonso, C.P. |

| Occupation | Roman Catholic priest, actor, autobiographer |

| Known for | I Was a Monk: The Autobiography of John Tettemer (Knopf, 1951), and an uncredited role as the priest, Montaigne, in the 1937 Academy Award-winning film, Lost Horizon |

| Spouse(s) | Ruth Elizabeth Roberts |

Formative years

Born in St. Louis, Missouri on May 16, 1876, John M. Tettemer was a son of Hanora Moynihan, a native of County Kerry, Ireland who had emigrated to America with her parents as a child, and Harvey J. Tettemer, a New Jersey native and manufacturer who became "the first man to bring shoe machinery west of the Mississippi river," according to historian Walter Barlow Stevens.[3][4] Per Tettemer:[5]

My parents made a fine combination. My father, Harvey Tettemer, was Pennsylvania Dutch and Presbyterian. My mother, Nora Moynihan, was County Kerry Irish Catholic, from Cloughnareeny, a place not important or even large enough for sophisticated maps of the world to show....

Mother had come to America with her father and many brothers when she was fourteen years old.... She was a born story-teller. Her mother was a Connor of County Cork; telling us tales of Roderick, last high King of Ireland, she made us feel that it was exciting, but no cause for thinking ourselves better than anyone else....

The atmosphere of our home was strongly religious.... My first record of a game is playing priest and hearing my playmates' confessions through the cane bottom of an overturned chair. The oldest brother, Harvey, would play at saying Mass and rigged up an altar in the back parlor, with candles and flowers and such linens as he could beg or remove surreptitiously from Mother's linen cupboard.... I was his altar boy. My duty was to swing the censer, made of a tin can containing hot water, which I replenished whenever the steam ("smoke") died down.

His family experienced a brief period of financial difficulty when competitors to his father's business began operating in St. Louis. As a result, his mother took a job "as forewoman of the sewing girls" in a factory nearby. In addition, his father was able to obtain an unsecured loan from Morris Levi, a Jewish businessman in St. Louis. Tettemer would later recall that "Father used the incident to instill in us some understanding of a people that had experienced harsh tribulations throughout its history, and to lay on us the precept of judging men as individuals and children of God, not accepting ready-made, often prejudiced estimates."[6]

During his early childhood years, John Tettemer's older sister, Mary, passed away. Sometime around this time, he also developed a speech defect which made it challenging for him "to pronounce certain combination of consonants." He later observed that this caused him to be "shy and silent," becoming even more so when teased by his siblings and other children. "I would listen like a small ghost to a story being told, or would lose myself in some book." His discomforts made him "sensitive to emotional appeals, in music, in tales of heroism and pathos, and to beauty in color," and "equipped [him] with a spontaneous sympathy for the feelings of others, whether human beings or animals, and with a sense of the utter wrongness of doing anything that may hurt." Although the defect lessened as he entered school, the condition had left its mark. The "fear of it ran deep and I became adept at substituting easier words for those which were difficult for me."[7]

Educated in the parochial schools of St. Louis (St. Bridget's), John Tettemer excelled at grammar and mathematics,[8] and was deemed ready for his First Communion by 1885.[9] During summer breaks, he resided on the Montgomery County, Missouri farm of an aunt and uncle "about ninety miles from St. Louis," where he "rode horseback full-tilt over the countryside," and helped with grain threshing. After completing his schooling at St. Bridget's at the age of 14, he engaged in "a supplementary year of English, Latin, algebra, and geometry." His father then helped him obtain a job with the John L. Boland Book & Stationery Company, "the largest wholesale bookstore west of Chicago," for which he was paid $15 per month to assist with office work and run errands. After several years in that role, he "was promoted to wholesale billing," where he assisted with the company's nationwide invoicing, a job he later noted had honed his powers of concentration. Ultimately, he left that job due to burdensome overtime hours. He then found similar work with the William A. Orr Shoe Company, a firm managed and partly owned by his father.[10]

While recuperating at home from a cold at the age of 16, his mother gave him several religious books to read, including Alban Butler's The Lives of Saints which, he later said, "aroused in [him] a burning desire to do something with [his] own life that would have worth." At this juncture, he began reading only books which were religious in nature, "especially longer biographies of the saints," and became increasingly enthralled by the life stories of monks, whom he had come to believe were "the only ones who comprehended the true meaning of existence." This, is turn, inspired him to increase his attendance at church services. Sometime around this time, his 19-year-old sister, Nora, with whom he had shared an interest in entering the religious life, fell ill with a severe cold; she died from pneumonia just a few weeks later.[11]

Religious life

John Moynihan Tettemer subsequently "entered the Passionist Order of Monks in 1894," according to the Sydney Morning Herald, "and made his theological studies in Rome, where he was ordained by Cardinal Respighi in 1901."[12][13] Given the religious name of "Father Ildefonso, C.P.," (also reported in newspapers as "Father Alphonso"), he was assigned to the Passionist Monastery in Normandy, Missouri (known officially as "Our Lady of Good Counsel," but sometimes also referred to as "the Little Rome of the West"). The first Passionist monastery to be established west of the Mississippi River, it had been dedicated on June 7, 1891.[14] John Tettemer later explained his decision:[15]

I chose [the Passionist Order] for two particular reasons. I learned that it was the strictest and most contemplative of any of the modern orders which sprang up so numerously in the Church after the Counter-Reformation, and that it retained to a remarkable degree the monastic spirit and customs of the more ancient orders. Moreover, it maintained the original fervor of spirit of its founding, and strict observance of the rule.

In 1907, he was appointed as director of the International College in Rome[16][17] and, in 1914, was appointed Consulator General of the Passionist Order.[18] Per Tettemer:[19]

In the spring of 1914, while still rector of the monastery in Kansas, I received a cablegram from Rome announcing my election, at the General Chapter then in session, to the office of Consulator General of the Order. This is the second highest office in the order, the general being the head.

I was only thirty-eight years of age, and this was big and unexpected news. The consulator, or assistant general, is usually chosen among the older, more experienced members of the order, after long years of service in successive offices.... My duties [in Rome] would be more of an advisory nature, as the general and his four consultors ... formed the executive body that ruled the order. I would be consulted and would render my vote in all important matters pertaining to governing the order, but would have none of that detail work involving harassing decisions and the giving of orders, which I never found easy....

I stayed a day or two with my mother [in St. Louis], and then said a last good-by to her. My term of office was to be six years; she was already in her seventies and she really knew this time that she could hardly expect to see me again....

My father had died a year or two before, at the age of about seventy-six. He had been knocked down by an automobile as he was crossing the street, and his hip-bone fractured. The bone would not knit at his age, and he was an invalid in a wheelchair for six months.... I was permitted once or twice in that time to visit him, but when pneumonia supervened as a delayed result of the shock of the accident, I was not present.

....As my father had been a leading Catholic layman of St. Louis, a great concourse of priests and laymen attended the funeral in the parish church. My brother and I said our Masses for Father at the two side-altars while the solemn requiem was being celebrated at the high altar, with the sanctuary crowded with priests.

After decades of religious training and service in one of the most austere branches of his church, he began to suffer health problems, and was ordered by his physician to take time away from his job to rest. During his recuperation, as he reflected on his life's direction, he developed an appreciation for contemplative practice, and when writing his autobiography later in life, described what had happened to him during this time:

My own native mind had had little opportunity to assert itself in the preceding years, as it had been too occupied with studying and teaching the ideas of others.... During my 'quiet time,' realizing this, I allowed my mind total freedom to open to the riddle of the mystery of existence, which had marked the birth of my philosophic mind at the age of twenty or thereabouts and always had held a fascination for me in the years between.... A new faculty of knowing seemed to be born in me, in the quiet stillness yet intense activity of consciousness within me. I seemed to touch the heart of reality, the very essence of existence, with a directness, an immediacy, rendering all my former knowledge false and illusory.[20]

As a result, he requested release from his church obligations in 1916, a release which was subsequently granted by Rome. After leaving the priesthood, he then embarked on a more traditional journey.[21]

Family and spiritual community

On Friday, July 1, 1921, Hanora Tettemer, the 79-year-old widowed mother of Rev. John M. Tettemer, died in St. Louis. The St. Louis Post-Dispatch reported in its July 3 edition that the she had suffered a stroke the previous Tuesday, and that "[s]olemn high mass [would] be sung at St. Paul's Church in Pine Lawn by her son, the Rev. Joseph H. Tettemer, the pastor," on Monday, July 4.[22] This same funeral notice also mentioned that the Rev. John M. Tettemer was "stationed in Rome, where he is a member of one of the Roman Catholic congregations."

Still active religiously during the 1920s, the Right Reverend John M. Tettemer, Auxiliary Bishop of the Liberal Catholic Church, was one of several celebrants at the opening ceremonies of the Theosophical Society in America's convention in Chicago, Illinois in August 1926. Among those in attendance were theosophist and women's rights activist Annie Besant.[23]

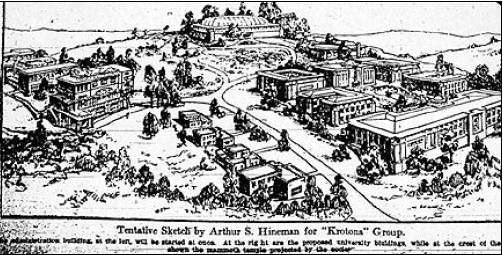

John M. Tettemer then also officiated at the 1927 wedding of Susan L. Warfield, of Hollywood, to the Right Reverend Irving S. Cooper, Regionary Bishop of the Liberal Catholic Church in the United States and a lecturer for the Theosophical Society in America. The ceremony was held in the open-air amphitheater at Krotona. (One of the three most important centers of learning for Theosophical Society members during the 20th century, Krotona was located in Ojai, California.) Among those in attendance were Annie Besant and her protege, the philosopher Jiddu Krishnamurti.[24]

Before the decade was out, John M. Tettemer also became a family man. In 1928, he wed Ruth Elizabeth Roberts (1905-1982), a native of Great Britain and, in 1934, began to make a new life with her in California in "the mountains behind Beverly Hills," according to the foreword to his book, I Was a Monk.[25] Their three children were born between 1931 and 1935.[26]

That same year (1928), The Right Reverend John Tettemer was based at St. Alban's cathedral in Los Angeles, but also officiated at church functions throughout California, including administering the rite of confirmation at St. Raphael's Liberal Catholic Church in Oakland.[27]

Business and creative work

When filing an application for a U.S. Passport in 1921, Tettemer stated that he was planning a trip both for his health and “to import American manufactured goods & raw materials to Europe.”[28]

From 1937 to 1943, he was cast in three uncredited film roles in Hollywood. In 1937, he performed the role of the priest, Montaigne, in the Academy Award-winning film, Lost Horizon. In 1942 and 1943, respectively, he played a "Salvation Army Worker" and "Minister" in "Syncopation" and "The Leopard Man." According to the Internet Movie database, IMDB, his last name was spelled as "Tettener" on the cast rosters of those films.[29] A 1940 edition of The Pittsburgh Press revealed more about how he became involved in the motion picture industry:[30]

A handsome, white-haired man, dressed like a clergyman, stood on a crowded platform and delivered an opening invocation for a national political convention. The delegates and gallery guests were extras hired for Frank Capra's "Meet John Doe" ... part of the script written by Robert Rlskin. But there seemed to be something especially real about it. When a sequence of shots had been made, a bystander went over to the benign-looking speaker and said, "Were you ever a preacher or a priest? With that face, and the way you talked, you certainly" An actress interrupted: "I don't know who you are, but I wanted to say that that was a marvelous job. You had me praying, too." "Thanks," said the elderly man. "Character parts like that seem to be rather easy for me, I was a Tibetan monk in "Lost Horizon." My name's John Tettemer." The actor usually doesn't go into much detail about himself because there's so much to tell. For example, he recently completed an autobiography.... His publishers wired they'd hold the manuscript until he could write a second volume bringing his life up to date. It happens that John Tettemer has been a monk, a priest, a teacher of priests, a specialist in canon law and theology for two colleges of cardinals, and assistant general (or vice chancellor) of the Papal College in Rome. It was in 1918 that he asked to be released from his vows. Plunged suddenly into the practical world, Tettemer taught Latin, French and mathematics. He found a few pupils in chess; then he learned bridge and taught that. In muddled Europe after the war, he tried the import-export business, did well, bought a couple of inventions which he brought to America and couldn't sell. He spent a year reading proof for an encyclopedia, tried mining and oil reclamation, and launched an advertising agency in Denver. The latter did all right until his partner absconded with all the assets. Tettemer came to California, ran a filling station, managed apartment houses, began tutoring college students, bought a small corner of the old Raymond Hitchcock estate near Hollywood and now lives there with his wife. Acting was about the only thing he hadn't tried, and he wasn't considering it when he had lunch with friend, John Burton, who was playing in "Lost Horizon," in 1937. Frank Capra spotted him and suggested a test for the Grand Lama role. But Tettemer appeared much too robust to be that saintly ancient; he became the monk who had been a pupil of Chopin. Much of his part had to be cut out, but Capra sought him again for "Meet John Doe," and there's little doubt that Hollywood's greatest scholar will have plenty of character roles after this if he wants 'em. Ever since leaving Rome, Tettemer has continued to explore all philosophies. It doesn't seem to have been the panicky groping of a disillusioned, bewildered man. He says he has the utmost sympathy with all religions “because each is effort to give form to faith." Occasionally Tettemer visits his old friends in the Passionist monastery at Sierra Madre, where he spent 25 years....

A U.S. Census worker described Tettemer's 1940 occupation as "writer and tutor."[31] According to the Los Angeles Times, "When John Moynihan Tettemer died in 1949 at the age of 73, he left the manuscript of an unfinished autobiography. Most of it he had written in a tiny adobe house on the desert near Victorville." This manuscript was then "edited by an old friend, Janet Mabie, after his death," and published by Knopf in 1951.[32] The book went on to become a selection for spirituality-based book clubs, as well as the subject of sermons by religious leaders of various denominations.[33]

Nicknamed "John the Divine" by his friends, Tettemer was an "expert athlete [and] equally skillful chess-player [who] was as much at home with people as with solitude," according to Jean Burden, the woman who wrote the foreword to his book.[34] "Expert mountain-climber, skater, skier, and tennis-player, chess enthusiast, voracious reader of everything new in non-fiction and anything exciting in murder mysteries, a stickler for accuracy and for the correct use of words, vigorous individualist and champion of justice and American democracy ... [who loved God through his fellow men" was how Tettemer was described by John Burton in the introduction to Tettemer's autobiography.[35]

Death and burial

John Moynihan Tettemer died in Los Angeles County, California on May 14, 1949. He was then buried at that county's Westwood Memorial Park.[36] Slightly more than three decades later, his widow, Ruth Elizabeth (Roberts) Tettemer, followed him in death, and was also laid to rest at the Westwood Memorial Park.[37] Their daughter-in-law, Susan (Cronyn) Tettemer (1934-2004), the daughter of actress Jessica Tandy and stepdaughter of actor Hume Cronyn, was then also laid to rest at the same cemetery following her passing in 2004.[38]

References

- Tettemer, John Moynihan. I Was a Monk: The Autobiography of John Tettemer. [1st ed.] New York: Knopf, 1951.

- "Bookman's Notebook: 25 Years a Monk." Los Angeles: The Los Angeles Times, October 8, 1951.

- John M. Tettemer (John Moynihan Tettemer), in U.S. Passport Applications. Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, 1921.

- Stevens, Walter Barlow. Centennial History of Missouri (the center state), one hundred years in the Union (1820-1921), Vol. 5. St. Louis, Missouri and Chicago, Illinois: The S. J. Clarke Publishing Company, 1921.

- Tettemer, John. I Was a Monk, pp. 4-6.

- Tettemer, John. I Was a Monk, pp. 9-10.

- Tettemer, John. I Was a Monk, pp. 10-11, 34.

- Tettemer, John. I Was a Monk, p. 11.

- Los Angeles Times.

- Tettemer, John. I Was a Monk, pp. 16-23.

- Tettemer, John. I Was a Monk, pp. 25-26, 34.

- The Rev. John Tettemer, in "Liberal Catholic Church." Sydney: The Sydney Morning Herald, May 24, 1926.

- Rev. John Tettemer, in "News of City Churches." St. Louis, Missouri: St. Louis Post-Dispatch, May 9, 1903.

- Carbonneau, C.P., Father Robert. "NY Times Passionist History Pt. 1 (1886-1923),", in The Passionist Heritage Newsletter, Vol. 18, Issue 2.Historical Commission of the Province of St. Paul of the Cross (Eastern U.S.A): Fall 2001.

- Tettemer, John. I Was a Monk, p. 28.

- Rev. John Tettemer, in "Honored." St. Louis, Missouri: St. Louis Post-Dispatch, August 23, 1907.

- DeMarco, Frank. "John Tettemer's experience." I of my own knowledge: retrieved online April 2, 2018.

- "John Moynihan Tettemer." C. W. Leadbeater: retrieved online April 2, 2018.

- Tettemer, John. I Was a Monk, p. 11, pp. 213-215.

- Tettemer, John. I Was a Monk.

- Tettemer, John. I Was a Monk.

- "Mrs. Hanora Tettemer Dies: Mother of Two Priests to Be Buried at Pine Lawn." St. Louis: St. Louis Post-Dispatch, July 3, 1921.

- "'Boy Messiah' Avoids Initial Meet of Cult: Young Hindu at Chicago Is at Hotel as Ceremony of Order Opened: Plans Speech Later: Morning Theosophist Meet Extremely Colorful as Rites Observed." San Bernardino, California: San Bernardino Sun, August 30, 1926.

- Ross, Joseph E. Krotona, Theosophy & Krishnamurti 1927-1931: Archival Documents of the Theosophical Society's Esoteric Center, Krotona, in Ojai California, vol. 5, p. 11. Ojai, California: Krotona Archives, 2011.

- Burden, Jean. "Foreword," in I Was a Monk: The Autobiography of John Tettemer. [1st ed.] New York: Knopf, 1951, p. xi.

- Tettemer, John M. and Ruth, et. al., in U.S. Census (Los Angeles, California). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, 1930 and 1940.

- Rt. Rev. John M. Tettemer. Oakland, California: Oakland Tribune, January 26 and 28, 1928.

- U.S. Passport Applications.

- "Lost Horizon" (1937), "Syncopation" (1942), and "The Leopard Man" (1943). IMDb: retrieved online, April 2, 2018.

- "Prayer By Ex-Priest Stirs Screen Extras: Invocation in Picture Brings Queries and Hollywood's Greatest Scholar Is Revealed As Former Theologian." Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: The Pittsburgh Press, September 14, 1940.

- U.S. Census.

- Los Angeles Times.

- "Unity Minister, Wife, Will Be Honored Tonight." Santa Cruz, California: Santa Cruz Sentinel, January 23, 1953.

- Burden, Jean. "Foreword," in I Was a Monk, p. x.

- Burton, John. "Introduction," in I Was a Monk: The Autobiography of John Tettemer. [1st ed.] New York: Knopf, 1951, p. xiv.

- John Moynihan Tettemer. Find A Grave: retrieved online, April 2, 2018.

- Ruth Elizabeth Tettemer. Find A Grave: retrieved online May 1, 2018.

- Susan Cronyn Tettemer. Find A Grave: retrieved online May 1, 2018.

External resources

- "Apostolic Succession of the Old Catholic Church of BC" (list of Bishops and Consecrators). British Columbia, Canada: The Old Catholic Church of BC.

- Krotona Institute of Theosophy. Ojai, California.

- Tettemer, John Moynihan. I Was a Monk: The Autobiography of John Tettemer. [1st ed.] New York: Knopf, 1951 (online version provided via the Hathi Trust Digital Library, University of Michigan).

- The Theosophical Society in America. Wheaton, Illinois.

Filmography

According to the American Film Institute, John Tettemer was credited with performances in these films:

- "Lost Horizon" (credited as Montaigne, directed by Frank Capra), 1937.

- "Meet John Doe" (credited as cleric at John Doe rally, directed by Frank Capra), 1941.

- "Syncopation" (credited as Salvation Army worker, directed by William Dieterle), 1942.

- "The Leopard Man" (credited as the minister, directed by Jacques Tourneur), 1943.

External links