John Jackson Dickison

John Jackson Dickison, known as J. J. Dickison (March 27, 1816 – August 20, 1902), was an officer in the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War. Dickison is mostly remembered as being the person who led the attack which resulted in the capture of the Union warship USS Columbine in the "Battle of Horse Landing". This was one of the few instances in which a Union warship was captured by land-based Confederate forces during the Civil War and the only known incident in U.S. history where a cavalry unit sank an enemy gunboat.[1] Dickison and his men were victorious in all of his raids against the Union troops in Florida, including his raid in Gainesville what is known as the Battle of Gainesville. Tragedy struck Dickison, when one of his sons, both of whom served under his command, was killed during a raid.

John Jackson Dickison | |

|---|---|

Then-Capt. John Jackson Dickison (1864) | |

| Nickname(s) | "The Swamp Fox" |

| Born | March 27, 1816 Monroe County, Virginia (now part of West Virginia) |

| Died | August 20, 1902 (aged 86) Okahumpka, Florida |

| Place of burial | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | 1862–1865 |

| Rank | |

| Commands held | |

| Battles/wars | American Civil War

|

| Other work | Adjutant General of Florida, author |

Early years

Dickison was born in Monroe County, Virginia (now part of West Virginia), and was raised in South Carolina. There Dickison received his primary and secondary education. He lived in Georgetown, where he became a successful businessman as a cotton merchant. Dickison joined the South Carolina Militia where he received his military training and was commissioned an officer in the cavalry. In 1845, he married Mary Elizabeth Ling and had two sons, Charles and R. L. Dickison. In 1857, Dickison moved to Ocala, Florida, where he purchased a plantation which he named "Sunnyside". His plantation was very successful and there he continued to flourish in his business.[2]

American Civil War

On December 12, 1861, Dickison was asked by the Confederate southern commanders if he would join them in their quest upon the outbreak of the American Civil War and he accepted. He was commissioned a Lieutenant under Captain John M. Martin and served in the Marion Light Artillery in Fort Clinch. On July 2, 1862, he was promoted to Captain and ordered to create and command a new cavalry unit, Company H of the Second Florida Cavalry. Dickison had returned from a successful raid and received the following recognition from Major General Sam Jones, his Commanding officer:[2][3]

I directed Captain Dickison, of the Second Florida Cavalry, who had just returned from a most successful raid east of the Saint John's, to endeavor to get in the rear, and concentrated on a large a force as I could at Newnansville. The enemy meetings, perhaps, more opposition than they had anticipated, fell back and were followed by Captain Dickison, who attacked them on the mainland, near Cedar Keys; and though his force was outnumbered five to one, the enemy retreated to Cedar Keys, after a sharp skirmish, leaving a portion of their dead on the field. Captain Dickison reports that he killed and wounded between sixty and seventy, and captured a few, with very slight loss on his part. I have heretofore frequently had occasion to report the gallant and valuable services of Captain Dickison and his command, and to present the captain, as I do now, to the favorable notice of the Government.

The Battle of Horse Landing

Lola Sánchez was moved to become a Confederate spy after her father was imprisoned by Union soldiers on false accusations that he was a Confederate spy. His residence, on the banks of the St. John's River opposite Palatka, Florida, was occupied by the Union forces. On May 21, 1864, Lola Sánchez overheard three Union officers discuss the plans that their unit had for a raid against the Confederate forces. The plan was to go into effect the next morning and consisted of a surprise attack on the Confederates while they slept with the aim of proceeding towards St. Augustine to "liberate" supplies for the Union Army.[4][5]

She decided that it was of utmost importance to notify Captain Dickison at Camp Davis, just a mile and a half from her home. Her sisters agreed to help by covering up her absence. Sánchez left her house that night and traveled, through the forest, alone on horseback. She reached the ferry and the ferryman minded her horse while she crossed the river. She came upon a Confederate picket and told him what she heard, however the picket was unable to leave his post and lent her his horse. She then proceeded to the camp where she met with Capt. Dickison. After the meeting she returned home, the whole event took an hour and a half, and her absence went unnoticed by the Union soldiers in her residence.[4][6]

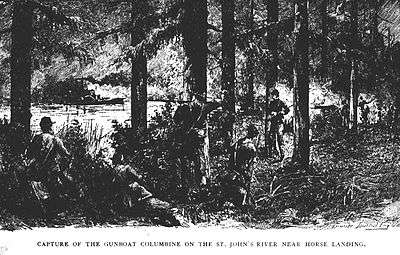

That night Dickison and his men crossed the St. Johns River and set a trap. They waited for the arrival of the Union transport and gunboat. On the morning of May 22, the Union forces plans were foiled when they were ambushed upon their arrival. At the exact moment necessary to succeed, Dickison raised his saber signaling his men to attack. The Confederate forces had placed artillery guns on the banks of the river and opened fire on the approaching Union gunboats. The skirmish which followed, officially known as the "Battle of Horse Landing", occurred south of St. Augustine. Union Colonel William H. Noble, commander of the 17th Connecticut Infantry, was wounded in the ambush and taken prisoner. The rest of the Union soldiers were either captured or killed. Dickison and his men captured the USS Columbine, a side-wheel steamer/gunboat under the command of Ensign Frank Sanborn. Sanborn made the following statement:[7]

After removing all the supplies and armament possible, they disabled and set the ship on fire. Of the 148 men aboard the Columbine, only 66 survived and the rest were killed. This was one of the few instances in which a Union warship was captured by land-based Confederate forces during the Civil War and the only known incident in US history where a cavalry unit sank an enemy gunboat.[1] The Confederates also captured a Union pontoon boat and renamed it The Three Sisters in honor of Lola Sanchez and her sisters.[5][6][8]

"The Battle of Gainesville"

During the months of June and July in 1864, Dickison and his men, which included his son Sergeant Charles Dickison, participated in several skirmishes with a Union force which was headed towards Palatka. On August 2, 1864, Dickison intercepted the contingent and forced them to surrender. He was not aware that some of the prisoners had concealed weapons. Without warning the prisoners exposed their weapons and opened fire. Dickison's son Charles was shot through the heart and fell from his horse mortally wounded.[2]

On August 17, 1864, Dickison was told that members of the Union Army had arrived at the town of Starke and that they had burned Confederate train cars. Dickison and his men then proceeded to head towards Gainesville to fight against the invading enemy in what would be known as Battle of Gainesville (not to be confused with the First Skirmish of Gainesville of February 14, 1864). Gainesville was held by the 75th Ohio Volunteer Mounted Infantry and members of the Company B of the 4th Massachusetts Cavalry.[9] They were caught totally unprepared by Cpt. Dickison and his men. The Union force was dispersed, but before they scattered into the woods they suffered 28 killed, 5 wounded and more than 200 captured.[2][10][11][12] The remaining Union forces in the north central Florida area withdrew to the garrisons at Jacksonville and St. Augustine. Gainesville would remain in Confederate control for the duration of the war. This however, did not keep some units from participating in minor raids.[13]

On October 24, 1864, a detachment of the 4th Massachusetts Cavalry returned to Gainesville to plunder. Dickison was alerted and made a swift attack which resulted in a 40 minute gunfight. Ten Union soldiers were killed and 23 were taken prisoners (this included eight men that were wounded).[10][11]

Final years and legacy

.jpg)

Dickison was captured near the town of Waldo and imprisoned. He was promoted to Colonel in May 1865, just a few days after the surrender of all CSA troops and paroled on May 20, 1865. Dickison helped Confederate Secretary of War John C. Breckinridge flee to Cuba. He provided Breckinridge with a boat; a lifeboat taken from the USS Columbine.[1][7] He continued to be active in CSA activities and was elected six times Commander of the Florida Division of United Confederate Veterans. In the late 1870s, he served as Florida's Adjutant General. Dickison wrote the Florida section of the 12 volume Confederate Military History.[14] Dickison and his wife Mary Elizabeth Dickison lived at Bugg Spring, in the town of Okahumpka, Florida, during the decades after the war. It was there that in 1889, Mrs. Dickison completed her book, "Dickison and His Men: Reminiscences of the War in Florida".[15][16]

In 1902, Dickison died in his home in Bugg Spring and is buried in Evergreen Cemetery, Jacksonville, Florida. A marker was placed on the site where Dickison and his men captured the USS Columbine by the Florida Confederation For The Preservation Of Historic Sites, Inc.[1] Another marker was placed at 1st St. NE & 3rd St. in the town of Gainesville in the location where the "Battle of Gainesville" took place.[17] There is also a marker in Waldo, Florida, where Camp Baker was located and where Dickison and his men bivouacked during the closing weeks of the conflict.[18] The Dickison cottage in Bugg Spring still stands and is now a private guest house.[15]

See also

References

- "Horse Landing Project". The Florida Confederation for the Preservation of Historic Sites website. Daytona Beach, FL: The Florida Confederation for the Preservation of Historic Sites, Inc. Archived from the original on 2011-07-28.

- Joseph E. Miller (April 14, 2010). "General J. J. Dickison (1816–1902)". Jacksonville Observer. Archived from the original on July 22, 2011. Retrieved June 1, 2011.

- George W. Davis, Leslie J. Perry, Joseph W. Kirkley, "February 13 1865. Action at Station 4, Fla", War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, series 1, vol.49, pp. 40–42, Washington: Government Printing Office 1897

- Rebecca M. Cuevas De Caissie (2011). "Hispanic Confederate Heritage – The Sanchez sisters". BellaOnline: Hispanic Culture Site. Retrieved June 1, 2011.

- William D. Chisolm (2008). "True heroine for the Confederacy to be honored". Columbia Star. Retrieved June 1, 2011.

- The Battle at Horse Landing; by Keith Kohl Archived 2011-09-28 at the Wayback Machine. Floridareenactorsonline.com. Retrieved on 2011-06-08.

- Roger Bull (December 18, 2005). "Waiting for the truth to surface". The Florida Times-Union. Retrieved June 1, 2011.

- "ST. Augustine in the Civil War"; BY: Gil Wilson. Drbronsontours.com. Retrieved on 2011-06-08.

- https://ehistory.osu.edu/books/official-records/065/0432

- Battle of Gainesville. Battleofolustee.org. Retrieved on 2011-06-08.

- "John Jackson Dickison (Capt. J.J. Dickison)". Sons of the Confederate Veterans website. Melbourne, FL: Sons of Confederate Veterans, Capt. J.J. Dickison Camp 1387. 2009.

- Alachua County Library. Heritage.acld.lib.fl.us. Retrieved on 2011-06-08.

- Detailed account of the battle Archived 2005-12-19 at the Wayback Machine. Floridareenactorsonline.com. Retrieved on 2011-06-08.

- Col. J. J. Dickison, Confederate Military History, a library of Confederate States Military History: Volume 11.2, Florida; Clement Anselm Evans, Ed. Perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved on 2011-06-08.

- Explore Southern History. Explore Southern History. Retrieved on 2011-06-08.

- Bugg Spring – Home of J.J. Dickison. Civilwarflorida.blogspot.com (2009-03-22). Retrieved on 2011-06-08.

- Florida Historical Markers Programs – Marker: Alachua. Flheritage.com. Retrieved on 2011-06-08.

- Dickison and His Men / Jefferson Davis' Baggage. Hmdb.org. Retrieved on 2011-06-08.

Further reading

- "JJ Dickison: Swamp Fox of the Confederacy"; by John Koblas; Publisher: North Star Press of St. Cloud, Inc.; ISBN 0-87839-149-5; ISBN 978-0-87839-149-3

- "Dickison and His Men: Reminiscences of the War in Florida" By: Mary Elizabeth Dickison (wife of J. J. Dickison) ; Publisher: San Marco Bookstore, Jacksonville, FL; 1st edition; ASIN: B0006EJRL8

- "Discovering the Civil War in Florida: A Reader and Guide"; by: Paul Taylor; Publisher: Pineapple Press; ISBN 978-1-56164-235-9; ISBN 978-1-56164-235-9; ASIN: 1561642355

- "Way Down Upon the Suwannee River: Sketches of Florida During the Civil War"; by: Gary Loderhose; Publisher: iUniverse; ISBN 0-595-15940-0; ISBN 978-0-595-15940-6

- "Touched by the Sun (Florida Chronicles)"; by: Stuart B McIver; Publisher: Pineapple Press; 1st edition; ISBN 978-1-56164-206-9; ISBN 978-1-56164-206-9; ASIN: 1561642061