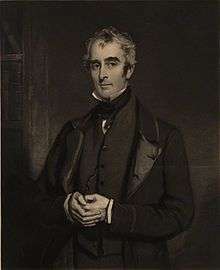

John Gibson Lockhart

John Gibson Lockhart (12 June 1794 – 25 November 1854) was a Scottish writer and editor. He is best known as the author of a biography of his father-in-law Sir Walter Scott, which has been called the second most admirable in the English language, after Boswell's Life of Johnson.

Early years

Lockhart was born on 12 June 1794[1][2] in the manse of Cambusnethan House in Lanarkshire to Dr John Lockhart, who transferred in 1796 to Glasgow, and was appointed minister, and his wife Elizabeth (d. 1834), daughter of Margaret Mary Pringle and Reverend John Gibson, minister of St Cuthbert's, Edinburgh.[3] His mother was a woman of considerable intellectual gifts.[4]

Lockhart attended Glasgow High School, where he showed himself clever rather than industrious. He fell into ill-health, and had to be removed from school before he was 12; but on his recovery he was sent at this early age to the University of Glasgow, and displayed so much precocious learning, especially in Greek, that he was offered a Snell exhibition at Oxford. He was not yet 14 when he entered Balliol College, Oxford, where he acquired a great store of knowledge outside the regular curriculum. He read French, Italian, German and Spanish, was interested in antiquities, and became versed in heraldic and genealogical lore.[4]

Blackwood's magazine and marriage

In 1813 he took a first class in classics in the final schools. For two years after leaving Oxford he lived chiefly in Glasgow before settling to the study of Scots law in Edinburgh, where he was elected to the Faculty of Advocates in 1816. A tour on the continent in 1817, when he visited Goethe at Weimar, was made possible by the publisher William Blackwood, who advanced money for a translation of Friedrich Schlegel's Lectures on the History of Literature, which would not be published until 1838.[4]

Edinburgh was then the stronghold of the Whig party, whose organ was the Edinburgh Review; and it was not till 1817 that the Scottish Tories found a means of expression in Blackwood's Magazine. After a somewhat hum-drum opening, Blackwood suddenly electrified the Edinburgh world by an outburst of brilliant criticism. John Wilson (Christopher North) and Lockhart had joined its staff in 1817. Lockhart shared in the caustic and aggressive articles that marked the early years of Blackwood; but his biographer Andrew Lang denied he was responsible for the virulent articles on Coleridge and on "The Cockney School of Poetry" of Leigh Hunt, Keats and their friends. Lockhart has been accused of the later Blackwood article (August 1818) on Keats, but he did show appreciation of Coleridge and Wordsworth.[4]

In 1818 the young man attracted the notice of Sir Walter Scott. He married Scott's eldest daughter Sophia in April 1820. Five years of domesticity followed, with winters spent in Edinburgh and summers at a cottage at Chiefswood, near Abbotsford, where Lockhart's child John Hugh was born; second son Walter and daughter Charlotte were born later in London and Brighton.[4]

In 1820 John Scott, the editor of the London Magazine, wrote a series of articles attacking the conduct of Blackwood's Magazine, and making Lockhart chiefly responsible for its extravagances. A correspondence followed, in which a meeting between Lockhart and John Scott was proposed, with Jonathan Henry Christie and Horace Smith as seconds. A series of delays and complicated negotiations resulted early in 1821 in a duel between Christie and John Scott, in which Scott was killed.[4]

Lockhart had called Keats a "vulgar cockney poetaster," due to what Lockhart considered to be Keats' relative lack of literary education. History, however, has tended to regard Keats as among the finest poets in English history.

Literary contributions

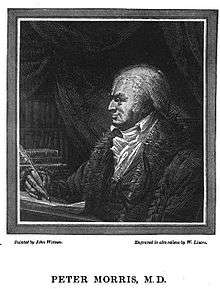

Between 1818 and 1825 Lockhart worked indefatigably. In 1819 Peter's Letters to his Kinsfolk appeared, and in 1822 he edited Peter Motteux's edition of Don Quixote, to which he prefixed a life of author Miguel de Cervantes. Four novels followed: Valerius in 1821, Some Passages in the Life of Mr. Adam Blair Minister of Gospel at Cross Meikle in 1822, Reginald Dalton in 1823 and Matthew Wald in 1824. However, his strength did not lie in novel writing. He also contributed to Blackwood translations of Spanish ballads, which in 1823 were published separately.[4]

In 1825 Lockhart accepted the editorship of the Quarterly Review, which had been in the hands of Sir John Taylor Coleridge since William Gifford's resignation in 1824.[4]

At this time he was living at 25 Northumberland Street in Edinburgh's New Town. In 1825 he sold the house to Andrew and George Combe.

As the next heir to the Scotland property belonging to his unmarried half-brother, Milton Lockhart, he was sufficiently independent. In London he had social success, and was recognised as an editor. He contributed largely to the Quarterly Review himself, particularly biographical articles. He showed the old, railing spirit in an article in the Quarterly against Tennyson's Poems of 1833. He continued to write for Blackwood,[4] producing for Constable's Miscellany Vol. XXIII in 1828 a controversial Life of Robert Burns. Snyder wrote of it, "The best that one can say of it today...is that it occasioned Carlyle's review. It is inexcusably inaccurate from beginning to end, at times demonstrably mendacious, and should never be trusted in any respect or detail."

Later works

Lockhart undertook the editorial supervision of Murray's Family Library, which he opened in 1829 with a History of Napoleon.[4]

However, his major work, and the one for which he is known, is the Life of Sir Walter Scott (7 vols, 1837–1838; 2nd ed., 10 vols., 1839). This biography included the publishing of a great number of Scott's letters. Thomas Carlyle assessed it in a criticism contributed to the London and Westminster Review (1837). Lockhart's account of the business transactions between Scott and the Ballantynes and Constable caused an outcry; and in the discussion that followed he showed bitterness in his pamphlet The Ballantyne Humbug handled. The Life of Scott has been called, after Boswell's Life of Samuel Johnson, the most admirable biography in the English language. The proceeds, which were considerable, Lockhart resigned for the benefit of Scott's creditors.[4]

His later years

Lockhart's later life was saddened by family bereavement, resulting in his own breakdown in health and spirits. His eldest son (the suffering "Hugh Littlejohn" of Scott's Tales of a Grandfather) died in 1831; Scott in 1832; Anne Scott in 1833; his wife Sophia in 1837; and the surviving son, Walter Scott Lockhart, in 1853. Resigning the editorship of the Quarterly Review in 1853, he spent the next winter in Rome, but returned to England without recovering his health; and being taken to Abbotsford by his daughter Charlotte, who had become Mrs James Robert Hope-Scott. He died there on 25 November 1854. He was buried in Dryburgh Abbey near the grave of Sir Walter Scott.[4]

Freemasonry

Like his father-in-law he was a Freemason although he was initiated in a different Edinburgh Lodge - Lodge Canongate Kilwinning, No. 2, on 26 January 1826.[5]

Legacy

Robert Scott Lauder painted two portraits of Lockhart, one of him alone, and the other with Charlotte Scott.

The composer Hubert Parry set one of Lockhart's poems to music, "There is an old belief", as part of his collection of six choral motets, Songs of Farewell.[6] The pieces were first performed at a concert at the Royal College of Music on 22 May 1916. The song/poem was later sung at the composer's funeral in St Paul's Cathedral on 23 February 1919.[7][8]

References

- https://www.nrscotland.gov.uk/research/learning/hall-of-fame/hall-of-fame-a-z/lockhart-john-gibson

- Rogers, Charles (1877). Genealogical Memoirs of the Family of Sir Walter Scott

- Matthew, H. C. G.; Harrison, B., eds. (23 September 2004), "The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography", The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, pp. ref:odnb/16904, doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/16904, retrieved 18 November 2019

-

- History of the Lodge Canongate Kilwinning, No.2, compiled from the records 1677-1888. By Alan MacKenzie. 1888. P.24.

- Shrock, Dennis (2009). Choral Repertoire. Oxford University Press, USA. ISBN 9780195327786. Retrieved 26 August 2018.

- Dibble, Jeremy (1992). C. Hubert H. Parry: His Life and Music. Clarendon Press. p. 496. ISBN 9780193153301.

- Keen, Basil (2017). The Bach Choir: The First Hundred Years. Routledge. pp. 96–7. ISBN 9781351546072. Retrieved 28 August 2018.

- Andrew Lang, The Life of J. G. Lockhart, 2 vols., London and New York, 1897

- Alfred William Pollard, The Life of Scott, 1900

External links

| Library resources about John Gibson Lockhart |

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: John Gibson Lockhart |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: John Gibson Lockhart |

- Works by John Gibson Lockhart at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about John Gibson Lockhart at Internet Archive

- Portrait, with wife (daughter of Walter Scott), by Robert Scott Lauder at the National Gallery of Scotland

- Photograph of John Gibson Lockhart at National Galleries of Scotland

- Lodge Canongate Kilwinning, No. 2. (Edinburgh)