George Combe

George Combe (21 October 1788 – 14 August 1858) was a Scottish lawyer and the leader and spokesman of the phrenological movement for over 20 years. He founded the Edinburgh Phrenological Society in 1820 and wrote the influential study The Constitution of Man (1828). Combe was trained in Scots law and had an Edinburgh solicitor's practice. After his marriage in 1833, Combe devoted himself in later years to promoting phrenology internationally.[1]

George Combe | |

|---|---|

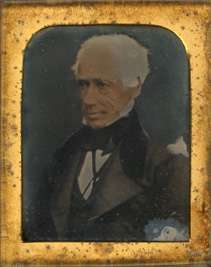

George Combe, 1836 by Daniel Macnee | |

| Born | 21 October 1788 |

| Died | 14 August 1858 (aged 69) Moor Park, Farnham, Surrey |

| Nationality | British |

| Known for | phrenology |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | phrenology writer |

Early life

George Combe was born in Edinburgh, the son of George Combe, a prosperous brewer in the city, and the elder brother of Andrew Combe. After attending the High School of Edinburgh and the University of Edinburgh, Combe entered a lawyer's office in 1804; and, in 1812, he began his own practice.

The Combe family lived together in a large home at 25 Northumberland Street in the New Town until at least 1833.[2]

The Phrenological Society

In 1815, the Edinburgh Review contained an article on the system of "craniology" devised by Franz Joseph Gall and Johann Gaspar Spurzheim, which was denounced as "a piece of thorough quackery from beginning to end." When Spurzheim came to Edinburgh in 1816, Combe was invited to a friend's house, where he watched Spurzheim dissect a human brain.[1] Impressed by this demonstration, he attended the second series of Spurzheim's lectures. Investigating the subject for himself, he became satisfied that the fundamental principles of phrenology were true — namely, "that the brain is the organ of mind; that the brain is an aggregate of several parts, each subserving a distinct mental faculty; and that the size of the cerebral organ is, caeteris paribus, an index of power or energy of function."

In 1820, Combe helped to found the Phrenological Society of Edinburgh, which in 1823 began to publish a Phrenological Journal. Through his lectures and writings, Combe drew public attention to phrenology in Continental Europe and the United States, and in his native United Kingdom.[1]

Debate with Hamilton

Combe began to lecture at Edinburgh in 1822, and published a Manual called Elements of Phrenology in June 1824. He took private tuition in elocution; contemporaries described him as clever and opinionated. Combe's discussions had an air of confidentiality and rather theatrical urgency. Converts came in, new societies sprang up, and controversies began. A second edition of the Elements, 1825, was attacked by Francis Jeffrey in the Edinburgh Review for September 1825. Combe replied in a pamphlet and in the journal. Sir William Hamilton delivered addresses to the Royal Society of Edinburgh in 1826 and 1827 attacking the phrenologists. A sharp controversy followed, including challenges to public disputes and mutual charges of misrepresentation, in which Spurzheim took part. The correspondence was published in the fourth and fifth volumes of the Phrenological Journal.[3]

Social interests: schools, prisons and asylums

In 1836, Combe stood for the chair of Logic at Edinburgh, against two other candidates, Sir William Hamilton and Isaac Taylor;[4] Hamilton won with 18 votes, against 14 for Taylor.[3] In 1838 Combe visited the United States and studied the treatment of criminals there. He initiated a programme of public education on chemistry, physiology, history and moral philosophy.

Combe sought to improve the provision of public education, advocating a national system of non-sectarian education.[5] He helped to set up a school in Edinburgh run on the principles of William Ellis, and did some teaching there himself on phrenology and physiology.[3] It was prompted by the London Birkbeck School, which had opened on 17 July 1848.[6][7][8] Combe was a significant figure in taking the view that the state should be involved with the educational system. His ideas were supported by William Jolly, an inspector of schools, and noted by Frank Pierrepont Graves.[9]

Combe was seriously concerned about prison reform. With the assistance of William A. F. Browne, he opened a debate about the introduction of humane treatment of psychiatric patients in publicly funded asylums.

Later life

John Ramsay L'Amy WS FRSE (son of James L'Amy) trained under Combe at his offices at 25 Northumberland Street in Edinburgh's New Town.[10][11]

In 1842, Combe delivered a course of 22 lectures on phrenology in the Ruprecht Karl University of Heidelberg, and he travelled much in Europe, inquiring into the management of schools, prisons and asylums.

On retirement, Combe lived in a substantial, elegant terraced townhouse, 45 Melville Street, in Edinburgh's West End.[12] He was revising the 9th edition of the Constitution of Man when he died at Moor Park, Farnham in August 1858. He is buried in the Dean Cemetery in Edinburgh against the north wall of the original section.[13]

Works

In 1817 his first essay on phrenology appeared in The Scots Magazine, soon followed by a series of papers on the same subject in the Literary and Statistical Magazine. These were collected and published in 1819 in book form as Essays on Phrenology, which in later editions became A System of Phrenology.

Combe's most popular work, The Constitution of Man, appeared in 1828, but was widely denounced as a materialist and atheist. He argued in the book: "Mental qualities are determined by the size, form and constitution of the brain; and these are transmitted by hereditary descent".

Combe was part of an active Edinburgh scene composed of people thinking about the nature of heredity and its possible malleability, such as Lamarck proposed. Combe himself was no Lamarckian, but in the decades before the publication of Darwin's Origin of Species, the Constitution was probably the single most important vehicle for the dissemination of naturalistic progressivism in the English-speaking world.[14]

His Answers to the Objections Urged Against Phrenology published in 1838 was followed in 1840 by Moral Philosophy and in 1841 by Notes on the United States of North America. Combe's Phrenology Applied to Painting and Sculpture came in 1855. The culmination of Combe's autobiographical philosophy appears in "On the Relation between Science and Religion", first publicly issued in 1857. Combe moved into the economic arena with a pamphlet on The Currency Question (1858). A fuller phrenological approach to political economy was set out later by William Ballantyne Hodgson.

Family

In 1833, Combe married Cecilia Siddons, a daughter of the actress Sarah Siddons and sister of Henry Siddons, author of Practical Illustrations of Rhetorical Gesture and Action (1807). She brought him a fortune and a happy – though childless – marriage, preceded by a phrenological check for compatibility. A few years later, he retired from work as a lawyer in comfortable circumstances.[3]

The large, simple headstone on Combe's grave in Dean Cemetery, Edinburgh lies against the north wall of the original cemetery, backing onto the first northern extension. Cecilia Siddons is buried with him.

Bibliography

- George Combe (1828), The Constitution of Man Considered in Relation to External Objects. J. Anderson jun. (reissued by Cambridge University Press, 2009; ISBN 978-1-108-00413-8)

- George Combe (1830), A System of Phrenology Edinburgh: J Anderson. Full Text Available at archive.org

- George Combe (1857), On the Relation Between Science and Religion. Maclachlan and Stewart (reissued by Cambridge University Press, 2009; ISBN 978-1-108-00451-0)

- Wright, Peter (August 2005). "George Combe—phrenologist, philosopher, psychologist (1788–1858)". Cortex. 41 (4): 447–451. doi:10.1016/s0010-9452(08)70185-0. PMID 16042021.

- Kaufman, M. H. (October 1995). "Circumstances surrounding the examination of the skull and brain of George Combe (1788–1858) advocate of phrenology". Proceedings of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh. 25 (4): 663–674. PMID 11608956.

- Sait, J. E. (1976). "The Combe collection in the National Library of Scotland". The Bibliotheck. 8 (1–2): 53–54. PMID 11634646.

- De Giustino, D (1972). "Reforming the commonwealth of thieves: British phrenologists and Australia". Victorian Studies. 15: 439–61. PMID 11678098.

- Walsh, A. A. (July 1971). "George Combe: a portrait of a heretofore generally unknown behaviorist". Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences. 7 (3): 269–278. doi:10.1002/1520-6696(197107)7:3<269::AID-JHBS2300070305>3.0.CO;2-6. PMID 11609418.

Notes

- "George Combe – Encyclopedia". www.theodora.com. Retrieved 23 September 2016.

- "Edinburgh Post Office annual directory, 1832-1833". National Library of Scotland. p. 39. Retrieved 18 February 2018.

- Stephen 1887.

- . Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

- Charles William Bardeen (1901). A Dictionary of Educational Biography. Harvard University. C.W. Bardeen.

- . Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

- "Surgeons' Square from The Gazetteer for Scotland". Retrieved 18 February 2018.

- Archer, R. L. (Richard Lawrence) (1921). Secondary education in the nineteenth century. University of California Libraries. Cambridge University Press.

- Miller, John T. (1922). Applied character analysis in human conservation. University of California Libraries. R. G. Badger.

- Biographical Index of Former Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh 1783–2002 (PDF). The Royal Society of Edinburgh. July 2006. ISBN 978-0-902-198-84-5.

- Edinburgh and Leith Post Office Directory 1832-33

- Edinburgh and Leith Post Office Directory 1857-8

- Find a Grave. Retrieved 5 July 2020.

- Jenkins, Bill (2015). "Phrenology, heredity and progress in George Combe's Constitution of Man". The British Journal for the History of Science. 48 (3): 455–473. doi:10.1017/S0007087415000278. PMID 25998794.

- Attribution

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to George Combe. |