John Douglas Woodward

John Douglas Woodward (July 12, 1846 – June 5, 1924), usually simply J.D. or Douglas Woodward, was an American landscape artist and illustrator.[2] He was one of the country's "best-known painters and illustrators".[4] He produced hundreds of scenes of the United States, Northern Europe, the Holy Land, and Egypt, many of which were reproduced in popular magazines of the day.

Life

Woodward was born on July 12, 1846[8] in Middlesex Co., Virginia, the son of John Pitt Lee Woodward and Mary Mildred Minor Woodward. The family moved while he was still very young and he spent his childhood in Covington, Kentucky, where J.P.L. Woodward became a successful hardware merchant. By 1861, at the age of 15[3] or 16,[2] he had begun studying art under the German painter T.C. Welsch in nearby Cincinnati, Ohio.[8] The family had Confederate sympathies and fled to Canada during the American Civil War. In 1863, though, John travelled to New York City where he studied until 1865 at Cooper Union and the National Academy of Design. He exhibited his first painting at the Academy in 1867.[3]

Initially he tried to earn a living as a landscape artist, taking his inspiration from the countryside of Virginia. (His family had settled in Richmond after the war ended in 1865.) However, he found it impossible to earn a living from fine art alone and was drawn to book illustration. In 1871, he received his first commission from Hearth and Home magazine, which took him on a sketching tour of the South; these drawings appeared as wood engravings in the magazine.[3]

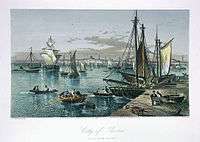

From 1872-3, he travelled extensively as one of the primary illustrators for D. Appleton & Company's series Picturesque America,[9][10] whose many engravings were based on sketches or watercolor paintings done on site. Woodward's drawings and paintings illustrated the sections on "Mackinac",[11] the "South Shore of Lake Erie",[12] the "Valley of the Connecticut",[13] "Boston",[14] the "Valley of the Housatonic",[15] the "Valley of the Genesee",[16] the "Eastern Shore",[17] "Lake Memphremagog",[18] "The Upper Delaware",[19] and the "Water-falls at Cayuga Lake".[20] His Connecticut Valley, from Mount Tom;[21] Boston, from South Boston;[7] and Quebec[22] were the basis for three of its steel engravings. The work was a major influence on the growth of American tourism and on its conservation and preservation movements.[23] It was massively popular and sold more than 100 000 copies by 1880.[23] During this period, Woodward also met and befriended Harry Fenn, another important illustrator on the project, despite the two working in different areas of the country.[24]

Appleton also employed him from 1874–5 to produce series on the Hudson River and the Transcontinental Railroad for its Art Journal. In 1875, Woodward married Maria Louise Simmons. He also produced illustrations for "A Century After: Picturesque Glimpses of Philadelphia".[3]

For Appleton's Picturesque Europe series, Woodward was sent to northern and eastern Europe. His work did not appear in the first volume of the series, which dealt with the British Isles. In the second and third volumes, his drawings and paintings illustrated the sections on "Old German Towns",[25] "Norway", "Norway (The Sogne Fjord, Nord Fjord, Romsdal)", "Sweden", "Dresden and the Saxon Switzerland", "Constantinople", "Russia", and "The Danube".[26] His Romsdalhorn and Bosphorus, Constantinople, were the basis for two of their steel engravings.[26]

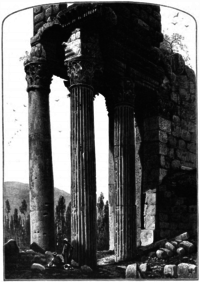

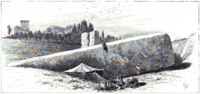

The sketches that formed the basis of Picturesque Palestine were compiled during Woodward and Fenn's two joint tours of Egypt and the Levant in the winters of 1877–78 and 1878–79. The two trips are documented in his correspondence with Woodward's wife and his mother. The pair received special permission to sketch inside and under the Mosque of Omar (the Dome of the Rock), although Woodward compared the streets of Jerusalem with the "dirtiest alleys of Baltimore". Oppressed by the heat, glare, and barrenness, the best he could say about the shore of the Dead Sea was "I suppose it is not so bad it couldn't be worse". Nazareth was "the worst",[2] while he was most impressed by the Syrio-Roman ruins at Baalbek.[27] In 1879, he returned to New York and spent much of the next three years readying the illustrations for print.[3] The works were hugely successful, with Woodward and Fenn earning $10 000 a year each in royalties on the Holy Land volumes.[2]

From 1882, he provided illustration for The Century Magazine and several books of poetry and, financially secure, was now able to devote more time to painting landscapes in oils and watercolors. He moved to Paris and Pont-Aven in France with his wife for most of 1883. They returned to New York in 1884, and Woodward continued over the coming years to paint pictures and provide illustrations for books (including Kingsley's "Song of the River" in 1887 and Tennyson's Bugle Song in 1888) and for journals such as The Century Magazine, Scribner's, and Harper's. He focused wholly on painting after the 1895 death of his father left him with a large inheritance.[3]

Between 1898 and 1901, Woodward and his wife traveled in Italy and Switzerland. In 1905, they settled in New Rochelle, New York, a popular art colony.[8] He sold paintings out of his studio[28] until his death on June 5, 1924.[8]

Legacy

Shrine Mont, owned by the Episcopal Diocese of Virginia, holds many of Woodward's original watercolors.[2] His correspondence is maintained as the collection "An Artist Abroad in the Seventies" at the State Library's Archives Division in Richmond, Virginia.[8]

References

Citations

- Pict. Pal., I.

- Ackerman (1994), p. 258.

- Rainey (2009).

- Joseph Pennell, cited in Rainey.[3]

- Pict. Pal., II, p. 469.

- Pict. Pal., II, p. 473.

- Pict. Amer. (1874), p. 233.

- Haverstock (2000).

- Pict. Amer. (1872).

- Pict. Amer. (1874).

- Pict. Amer. (1872), pp. 279–291.

- Pict. Amer. (1872), pp. 510–549.

- Pict. Amer. (1874), pp. 61–96.

- Pict. Amer. (1874), pp. 229–252.

- Pict. Amer. (1874), pp. 288–317.

- Pict. Amer. (1874), pp. 353–369.

- Pict. Amer. (1874), pp. 395–413.

- Pict. Amer. (1874), pp. 451–456.

- Pict. Amer. (1874), pp. 471–476.

- Pict. Amer. (1874), pp. 477–481.

- Pict. Amer. (1874), p. 80.

- Pict. Amer. (1874), p. 384.

- CSHSC.

- Ackerman (1994).

- Pict. Eur. (1878), p. 409–431.

- Pict. Eur. (1879).

- Ackerman (1994), p. 262.

- Ackerman (1994), p. 265.

Bibliography

- Picturesque America; or, The Land We Live In. A Delineation by Pen and Pencil of the Mountains, Rivers, Lakes, Forests, Water-falls, Shores, Cañons, Valleys, Cities, and Other Picturesque Features of Our Country. With Illustrations on Steel and Wood, by Eminent American Artists, Vol. I, New York: D. Appleton & Co., 1872.

- Picturesque America; or, The Land We Live In. A Delineation by Pen and Pencil of the Mountains, Rivers, Lakes, Forests, Water-falls, Shores, Cañons, Valleys, Cities, and Other Picturesque Features of Our Country. With Illustrations on Steel and Wood, by Eminent American Artists, Vol. II, New York: D. Appleton & Co., 1874.

- Picturesque Europe: A Delineation by Pen and Pencil of the Natural Features and the Picturesque and Historical Places of Great Britain and the Continent. Illustrated on Steel and Wood by European and American Artists, Vol. II, New York: D. Appleton & Co., 1878.

- Picturesque Europe: A Delineation by Pen and Pencil of the Natural Features and the Picturesque and Historical Places of Great Britain and the Continent. Illustrated on Steel and Wood by European and American Artists, Vol. III, New York: D. Appleton & Co., 1879.

- Picturesque Palestine, Sinai, and Egypt, Div. I, New York: D. Appleton & Co., 1881.

- Picturesque Palestine, Sinai, and Egypt, Div. II, New York: D. Appleton & Co., 1881.

- Picturesque Palestine, Sinai, and Egypt, Div. III, New York: D. Appleton & Co., 1881.

- Picturesque Palestine, Sinai, and Egypt, Div. IV, New York: D. Appleton & Co., 1883.

- "1872–74 Book: Picturesque America or The Land We Live In", Cedar Swamp Historical Society Collection, Long Island University, retrieved 26 September 2015.

- Ackerman, Gerald M. (1994), "John Douglas Woodward", American Orientalists, Paris: Mame for ACR, pp. 258–265, ISBN 2-86770-078-7.

- Haverstock, Mary Sayre (2000), "John Douglas Woodward", Artists in Ohio, 1787-1900: A Biographical Dictionary, Kent State University Press, p. 967, ISBN 9780873386166.

- Rainey, Sue (17 June 2009), "Drawn to Nature: John Douglas Woodward's Career in Art", Resource Library.

Further reading

- Rainey, Sue. J.D. Woodward's Wood Engravings of Colorado and the Pacific Railways, 1876-1878 (1993 Journal of the American Historical Print Collectors, Vol. 18, No. 2, pp. 2–12).

- Rainey, Sue & Stein, Roger B. Shaping the Landscape Image, 1865-1910: John Douglas Woodward (University of Virginia Press, 1997).

External links

- "John Douglas Woodward", Artcyclopedia.

- "John Douglas Woodward", artnet.

- "John Woodward", askART.