John Chapman (general)

Major General John Austin Chapman, CB, DSO & Bar, OBE (15 December 1896 – 19 April 1963) was a professional soldier in the Australian Army. Joining the army in 1913, he served as a junior officer during the First World War and saw action on the Western Front. After the war he was appointed to a number of staff and teaching positions prior to the outbreak of the Second World War. Appointed chief of staff, 7th Division, he served during the Syrian Campaign in 1941 before taking up important staff positions in Australia. He retired from the army in 1953 after 41 years of service and died in Sydney in 1963 at the age of 67.

John Austin Chapman | |

|---|---|

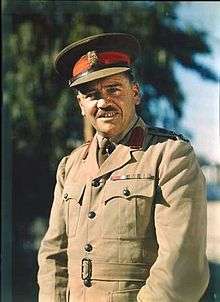

Brigadier John Chapman, 1942 | |

| Born | 15 December 1896 Braidwood, New South Wales |

| Died | 19 April 1963 (aged 66) Mosman, New South Wales |

| Buried | Northern Suburbs cemetery, Sydney |

| Allegiance | Australia |

| Service/ | Australian Army |

| Years of service | 1913–1953 |

| Rank | Major General |

| Service number | VX13844 |

| Commands held | Central Command (1950–51) Deputy Chief of the General Staff (1944–46) |

| Battles/wars | First World War

Second World War

|

| Awards | Companion of the Order of the Bath Distinguished Service Order & Bar Officer of the Order of the British Empire Mentioned in Despatches (2) Legion of Merit (United States) |

Early life

John Austin Chapman was born on 15 December 1896 in Braidwood, New South Wales, the son of Austin Chapman, the Braidwood representative on the New South Wales Legislative Assembly. He attended Christian Brothers schools in Sydney and Melbourne before entering Royal Military College, Duntroon in 1913.[1]

Military career

First World War

Upon graduation from Duntroon in 1915, Chapman was commissioned as a lieutenant in the Australian Army. Volunteering for the Australian Imperial Force (AIF), his first assignment was to 30th Battalion,[1] then being raised in New South Wales and destined for Egypt. The battalion duly embarked for Egypt in November 1915 and would remain there for several months, undertaking guard duties at the Suez Canal. Part of 8th Brigade, which was subordinate to the 5th Division, the battalion was transferred to the Western Front in July 1916 along with the rest of the division.[2]

Chapman, now a captain, was wounded due to a gas attack in November, and this necessitated his evacuation to England for treatment. He returned to the battalion in May 1917 as adjutant and served in this capacity until October. Promoted to major, he was attached to the Australian Corps and 5th Division headquarters. During the Hundred Days Offensive, he was acting brigade major of 8th Brigade. He was awarded the Distinguished Service Order (DSO) for his actions of 28 August 1918, when he carried out a reconnaissance of the front lines under heavy fire.[1] He was also appointed an Officer of the Order of the British Empire for his services while attached to divisional headquarters during the latter stages of the war.[3]

Interwar period

Chapman remained in the army after the cessation of hostilities, returning to Australia in June 1919. He married the following October, to Helena Mary de Booten, originally from Chile. The couple would go on to have four children.[1]

From 1919 to 1930, Chapman was posted to a series of staff appointments. He attended Staff College at Camberley in England from 1930 to 1933. He was then chief instructor at the Small Arms School in Randwick, Sydney from 1934 to 1938[1] before returning to Camberley in November with his wife to take up an instructor position, the first soldier from a British Dominion to do so.[4]

Second World War

Still in England when the Second World War broke out in September 1939, he was posted to the British 52nd (Lowland) Infantry Division as a staff officer but returned to Australia in January 1940, having been promoted to lieutenant colonel. Based in Melbourne, he was responsible for training at army headquarters before transferring to the reformed AIF in April 1940.[1] Promoted to colonel, he was chief of staff to Major General John Lavarack, the commander of 7th Division.[5] Commencing on 8 June 1941, the division participated in the two-month-long Syrian Campaign against the Vichy French during which Chapman earned a recommendation for a Bar to his DSO. This was duly gazetted and awarded in 1944.[6]

After the conclusion of the Syrian Campaign, Chapman was promoted to temporary brigadier and became responsible for the AIF Base Area in the Middle East. He later returned to Australia as deputy adjutant and Quartermaster General, based in Brisbane. Promoted to major general in September 1942, he was appointed as Deputy Chief of the General Staff in October 1944. He served in this capacity until March 1946.[1]

Postwar career

From May 1946, Chapman was based in Washington, D.C. as the army representative on the Australian Joint Service Mission to the United States.[7] After completing his four-year term in the United States (and being awarded a Legion of Merit), he had a spell as General Officer Commanding, Central Command before commencing his final post of Quartermaster General and member of the military board in February 1951. He was honoured with an appointment as Companion of the Order of the Bath in 1952.[1]

Later life

Chapman retired in December 1953 after 41 years of service in the army.[8] He died of cancer at his home in Mosman on 19 April 1963, survived by two sons and a daughter. His wife had predeceased him in 1961. He was buried with military honours in Northern Suburbs cemetery, Sydney.[1]

Notes

- Thompson, 1993, p. 403

- "30th Battalion". Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 5 June 2012.

- "OBE – John Austin Chapman". Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 5 June 2012.

- "Australian Officer's Appointment: English Staff Post". Sydney Morning Herald. 24 October 1938. Retrieved 5 June 2012.

- Long, 1953, p. 341

- "Bar to DSO – John Austin Chapman" (PDF). Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 5 June 2012.

- "General Chapman for Washington". The Courier Mail. 21 February 1946. Retrieved 5 June 2012.

- "Army's Top QM Retires". Morning Bulletin. 15 December 1953. Retrieved 5 June 2012.

References

- Long, Gavin (1953). Australia in the War of 1939–1945. Series 1 – Army: Volume II – Greece, Crete and Syria. Canberra, Australia: Australian War Memorial.

- Thompson, Roger C. (1993). Chapman, John Austin (1896–1963) in Australian Dictionary of Biography. Melbourne, Australia: Melbourne University Press.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to John Chapman (general). |