John Blackwell (engineer)

John Blackwell MICE (c. 1775 – 1840) was an English civil engineer, known for his work as superintending engineer of the Kennet and Avon Canal under John Rennie and later as the canal company's resident engineer.

John Blackwell | |

|---|---|

| Born | 1775 |

| Died | 28 September 1840 (aged 64–65)[1] |

| Resting place | St Lawrence's Parish Church, Hungerford, Berkshire |

| Citizenship | English |

| Spouse(s) | Frances Cooper (married 1808–1840; her death) |

| Children | 5 (including Thomas Evans Blackwell) |

| Engineering career | |

| Discipline | Civil engineering |

| Institutions | Institution of Civil Engineers |

| Employer(s) | Kennet and Avon Canal Company |

| Projects | Caen Hill Locks (1806–1810), Crofton Pumping Station, Wilton Water (1836) |

| Signature | |

Career

Blackwell was employed as an engineer on the Kennet and Avon Canal in 1806, working primarily as site agent on the Caen Hill Flight in Devizes, Wiltshire.[2][3] While John Rennie designed the flight,[lower-alpha 1] it was likely that construction was undertaken by the Kennet and Avon Canal Company and its engineers.[2] In 1808, shortly before the completion of the flight, Blackwell moved to work with Rennie on Crofton Pumping Station.[2] The following year, the pair built the remaining locks on the canal—two pound locks Oakhill Down near Froxfield,[2] which replaced an earlier single deeper lock. Original plans would have seen the lock be the canal's only staircase, although this proposal was never seen through.[5]

Blackwell was appointed the company's resident engineer on 19 July 1814, with a salary of £300 (plus £50 expenses to cover a horse).[2][3] Blackwell subsequently undertook essential maintenance of the waterway, ensuring passage for fast boats could be made—allowing transport between London and Bristol in five days.[3]

In 1824, Blackwell was instructed to survey a railway link between the canal and Salisbury; he had previously surveyed a railway between the River Avon and the collieries at Coalpit Heath.[3] In his research, Blackwell travelled to the north of England to visit some of the early railway systems, but remarked that "no great improvements have been made, there are limits to their powers which are nearly approached". The canal company accepted his opinion, and the scheme was cancelled.[2] He later visited the Liverpool and Manchester and Cromford railways.[2]

In 1829, Caen Hill had gas lighting installed under Blackwell's supervision.[3]

In 1832, Blackwell met English engineer Isambard Kingdom Brunel, who described him as a "bigoted, obstinate, practical man."[6] The meeting came during Brunel's work on an alternative route to the Black Dog Turnpike near Claverton.[7] The canal company was concerned that the new road may cause the clay hillside to slip into the waterway. Brunel, in return, was disparaging of the canal's upkeep, was dismissive of Blackwell for suggesting a landslide might be caused by the new road, and said that past slips were "considerably assisted by the bad management of the canal". He felt that Blackwell refused to justify his concerns.[6] Brunel continued with the project, but once the project was complete, the road did indeed slip as predicted.[6]

Blackwell was inducted into the Institution of Civil Engineers in 1833.[8]

In the early 1830s, a huge programme of work was undertaken, including the conversion of numerous turf-sided locks on the Kennet Navigation into brick and masonry lock chambers.[3] In approximately 1834, Blackwell built Ufton Lock, a brand new lock on a dedicated cut near Ufton Nervet in Berkshire. The new cut, of approximately 600 yards (550 m), bypassed a section of meandering river. The lock only changed the navigation level by approximately 2 feet (0.61 m), and when the waterway was restored in the 20th century, the lock was deemed unnecessary and it was removed. Blackwell engineered a similar cut at Burghfield, although the cut both left and rejoined the river above Burghfield Lock and no rebuilding was required.[9]

One of Blackwell's later projects was Wilton Water. Initially, Crofton Pumping Station used water from natural springs. In 1836, Blackwell created the 8-acre (3.2 ha) spring-fed reservoir to provide a greater water supply.[10] Blackwell's sluices and outfall from the reservoir were given Grade II listed status in 1986.[11]

Personal life

Blackwell married Frances "Fanny" Cooper in Burbage, Wiltshire, on 23 August 1808. They had five children—Emma (born in Burbage in 1808),[12] Eliza (born in Great Bedwyn in 1811),[13] Harriet (born in Devizes in 1814),[13] Louisa (b. 1817) and Thomas Evans Blackwell (b. 1819). At the 1861 census, Emma, Eliza and Harriett were all living together in Bath in John Eveleigh's Beaufort Buildings.[13][14]

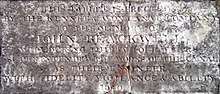

Blackwell died in Hungerford, Berkshire, on 28 September 1840.[15] He was buried in a vault in the churchyard at St Lawrence's Church in the town.[16] A memorial to Blackwell in the church reads:

IN MEMORY OF JOHN BLACKWELL, ESQ. C.E. FOR MANY YEARS A RESIDENT OF THIS TOWN, WHO DIED SEPT 28TH 1840, AGED 65 YEARS. AND OF FANNY, HIS WIFE; WHO DIED FEB 15TH 1840, AGED 56 YEARS. THEY DIED AT HUNGERFORD, AND WERE INTERRED IN A VAULT IN THE ADJACENT CHURCHYARD[1]

A plaque dedicated to Blackwell was erected on Prison Bridge, Devizes, after his death, reading:

"THIS TABLET IS ERECTED BY THE KENNET AND AVON CANAL COMPANY TO THE MEMORY OF JOHN BLACKWELL, WHO DURING THIRTY-FOUR YEARS SUPERINTENDED THE WORKS OF THE CANAL AS THEIR ENGINEER WITH FIDELITY, VIGILANCE, AND ABILITY"

Thomas became a civil engineer, and upon his father's death became engineer of the Kennet and Avon Canal. He emigrated to Canada in the 1850s.[17]

Footnotes

- Other sources[4] suggest it was Blackwell who designed the flight.

References

- "Church Monuments". www.hungerfordvirtualmuseum.co.uk. Hungerford Virtual Museum. Retrieved 30 October 2019.

- "John Blackwell". www.hungerfordvirtualmuseum.co.uk. Hungeford Virtual Museum. Retrieved 31 October 2019.

- Skempton, AW (2002). A biographical dictionary of civil engineers in Great Britain and Ireland (1. publ. ed.). London: Institution of Civil Engineers. p. 61. ISBN 9780727729392. Retrieved 16 July 2017.

- "Our place in history". www.claverton.org. Claverton Pumping Station. Retrieved 1 November 2019.

- Clew, Kenneth (1985). The Kennet & Avon Canal : an illustrated history (3rd rev. ed.). David & Charles. p. 73. ISBN 9780715386569.

- Maggs, Colin (2016). Isambard Kingdom Brunel : the life of an engineering genius. Stroud: Amberley Publishing. p. 61. ISBN 9781445640976.

- "History". Bathampton Village. 27 June 2015. Retrieved 31 October 2019.

- "John Blackwell - Graces Guide". www.gracesguide.co.uk. Grace's Guide.

- Allsop, Niall (1999). The Kennet & Avon Canal: A User's Guide to the Waterways between Reading and Bristol (4th ed.). Bath: Millstream. p. 48. ISBN 0948975288.

- "Timeline". Crofton Beam Engines. Kennet and Avon Canal Trust. Retrieved 31 October 2019.

- Historic England. "RESERVOIR OUTFALL AND SLUICES TO WILTON RESERVOIR WILTON RESERVOIR OUTFALL AND CANAL CROSSING LOCK, Grafton (1034022)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 31 October 2019.

- "Wiltshire baptisms index 1530-1917 Transcription". Find My Past. Wiltshire Family History Society. Retrieved 20 February 2018.

- "1861 England, Wales & Scotland Census Transcription". Find My Past. Wiltshire Family History Society. Retrieved 20 February 2018.

- "BEAUFORT WEST". British Listed Buildings. BritishListedBuildings.co.uk. Retrieved 20 February 2018.

- Kempton, AW (2002). A biographical dictionary of civil engineers in Great Britain and Ireland (1. publ. ed.). London: Institution of Civil Engineers. p. 61. ISBN 9780727729392. Retrieved 16 July 2017.

- "Berkshire Burial Index Transcription". Find My Past. Berkshire Family History Society. Retrieved 16 July 2017.

- "Water Supply for the Kennet and Avon Canal". The Butty (187): 16. 31 May 2009. Retrieved 16 July 2017.