Great Bedwyn

Great Bedwyn is a village and civil parish in east Wiltshire, England. The village is on the River Dun about 4.5 miles (7.2 km) southwest of Hungerford, 14 miles (23 km) southeast of Swindon and 6 miles (9.7 km) southeast of Marlborough.

| Great Bedwyn | |

|---|---|

View eastwards from Great Bedwyn showing river, canal and railway | |

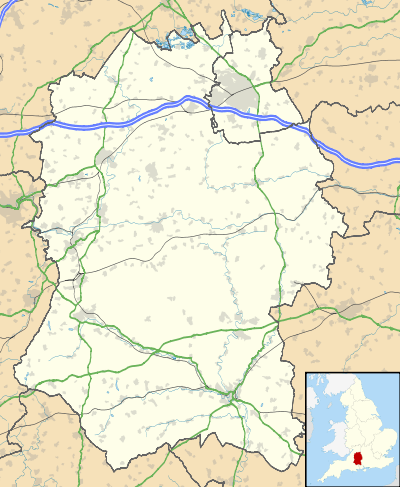

Great Bedwyn Location within Wiltshire | |

| Population | 1,353 (2011 census)[1] |

| OS grid reference | SU278645 |

| Civil parish |

|

| Unitary authority | |

| Ceremonial county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | Marlborough |

| Postcode district | SN8 |

| Dialling code | 01672 |

| Police | Wiltshire |

| Fire | Dorset and Wiltshire |

| Ambulance | South Western |

| UK Parliament | |

| Website | Parish Council Great Bedwyn |

The Kennet and Avon Canal and the Reading to Taunton line both follow the Dun and pass through the village. Bedwyn railway station is at Great Bedwyn and is the terminus of the rail commuter service via Reading and London Paddington.

The parish lies within the North Wessex Downs Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. It includes the hamlets of Crofton and St Katharines, together with Tottenham House and part of its estate, Tottenham Park.

History

Romans

A Roman road between Cirencester and Winchester crosses the parish, with Crofton on its route.[2] Castle Copse, south of Great Bedwyn village, is the site of a Roman villa.[3]

'Bedanheafeford', the Battle of Bedwyn

The battle of 'Bedanheafeford' between Aescwine of Wessex and King Wulfhere of Mercia in 675 is alleged to have been fought near Great Bedwyn.[4] The battle was originally recorded in the 675 AD entry of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle.[5]

A.H. Burne interpreted 'Biedanheafde' as an early version of Bedwyn, the derivation of the name being "the head of the Bieda" or "Beda", a stream running through the Bedwyns.[6] However placename interpretation is tenuous evidence for the battlefield location; the site of the battle has also been claimed for Beedon in Berkshire, and elsewhere.

The discovery of a number of skeletons at Crofton in 1892 by J.W. Brooke was later used to substantiate a local battlefield location. An account of the battle of Bedwyn was published by local historian Maurice Adams in 1903.[7] However, only excavation of these graves will confirm if they contain battlefield victims.

Brooke recorded that "I cannot assign any period to them, but the field over them is paved with flint weapons. On one visit I observed children building miniature castles with human femur and tibiae." In a letter to Maurice Adams, B.H. Cunningham described the graves, five to seven in number, "radiating from a common centre like the spokes of a wheel". Unfortunately he had made no notes of his finds and was writing from memory. Mrs M.E. Cunnington's study of Saxon grave sites in Wiltshire noted that there was no evidence to support the belief that the Crofton site contained Saxon graves.[8] Nearby finds consisted only of a La Tène earthenware pot. As the graves are within the site of a causewayed camp this is not surprising. Maurice Adams would not have known about the Crofton camp as it was undiscovered until an aerial survey in 1976.

Given the lack of evidence, Maurice Adam's confidence in a Bedwyn battlefield site cannot be shared. Until more substantial evidence about the Crofton graves can be gathered, there is no reason to suggest that the Bedwyn location, for an obscure 7th century battle, is anything more than a myth.

Reference in the will of King Alfred the Great

_-_BL_Stowe_MS_944%2C_f_30v.jpg)

The last will and testament of King Alfred the Great contains reference to Bedwyn. Describing his elder son Edward's inheritance he writes "And I grant him the land at Cannington and at Bedwyn and at Pewsey ..."[10] The Bedwyn of King Alfred was a large estate, whose territory included the modern parishes of Great and Little Bedwyn, Grafton, and Burbage. Bedwyn continues to enjoy an enduring royal pedigree. It belonged to the crown in 788, when part of the estate was granted to a crown servant called Bica. King Alfred's descendants held the estate until it was granted to Abingdon Abbey by King Edgar in 968. However the estate was recovered by King Athelred a few years later, and was recorded as a crown estate in the Domesday survey of 1086.[11] Although most of the estate had passed into private hands by the end of the mediaeval period, the execution of Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset, in 1552 resulted in the temporary return of much of Bedwyn to the crown. The disastrous finances of his descendants resulted in the great sale of 1929, and much of the former Bedwyn estate was purchased by the Crown Estate. They remain one of the largest landowners in modern Bedwyn.

Religious sites

Church of St. Mary

The Church of England parish church of Saint Mary the Virgin has 12th-century origins.[12] Beneath the church are substantial remains of a Saxon church begun in AD 905. In the chancel is a memorial to Sir John Seymour, father of King Henry VIII's wife Jane Seymour. The church is designated as a Grade I listed building,[13] and a 14th-century limestone cross in the churchyard is Grade II*.[14]

Thomas Willis (1621–1675), the great Oxford physician and natural philosopher, was born at Great Bedwyn on 27 January 1621 and was baptized on 14 February at the church.[15]

Church of St. Katharine

Built by T.H. Wyatt in 1861 as the estate church for Tottenham House. Grade II* listed.[16]

Canal and railway

The Kennet and Avon Canal was opened from Hungerford to Great Bedwyn in 1799, and from Great Bedwyn to Devizes in 1809.[2] There are four locks in the parish: Burnt Mill Lock and Bedwyn Church Lock near the village, and two of the Crofton flight to the southwest.

In 1862 the Great Western Railway built the Berks and Hants Extension Railway from Hungerford to Pewsey and Devizes, closely following the north bank of the canal, with a station named Bedwyn at Great Bedwyn. There are regular services to Reading and London Paddington, and the station is a railhead for Marlborough which is served by buses that connect with the trains.

Schools

A National School was built in Church Street, Great Bedwyn in 1835[18] and extended in 1856, becoming a Church of England primary school in 1963. The school moved to a new building on the outskirts of the village in 1994.[19]

In the northwest of the parish, a church school was opened at St Katharine's in 1865 and continues in use.[20]

The National School at East Grafton, opened in 1846, was used by children from Crofton; this school closed in 2011.[21]

Local government

The civil parish elects a parish council. It is in the area of Wiltshire Council unitary authority, which performs all significant local government functions.

In 1895 the southern portion of Great Bedwyn parish (south of the railway, including Wolfhall and East Grafton) became a new parish called Grafton.[2] Wolfhall was transferred to Burbage parish in 1988.[22]

Parliamentary representation

Great Bedwyn was a parliamentary borough which elected two Members of Parliament (MPs) to the House of Commons from 1295[2] until 1832, when the borough was abolished by the Great Reform Act.

The parish now falls within the Devizes constituency.

References

- "Parish population 2011". Neighbourhood Statistics. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 11 March 2015.

- "Victoria County History – Wiltshire – Vol 16 pp8-49 – Great Bedwyn". British History Online. University of London. Retrieved 27 November 2015.

- Historic England. "Castle Copse Roman Villa (224845)". PastScape. Retrieved 30 November 2015.

- Pearson, Michael (2003). Kennet & Avon Middle Thames:Pearson's Canal Companion. Rugby: Central Waterways Supplies. ISBN 0-907864-97-X.

- Kirby, D.P. (2002). The Earliest English Kings. Routledge. ISBN 1134548133. Retrieved 29 November 2015.

- Burne, Alfred (1950). The battlefields of England. London: Methuen. ISBN 0-06-470833-0.

- Adams, Maurice (1903). Savenake, Wolfhall, Tottenham & the Battle of Great Bedwyn. London: not known.

- Cunnington, M.E. (1934). "Wiltshire in Pagan Saxon Times". Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Magazine. Devizes. 46.

- Charter S 1507 Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine at the Electronic Sawyer

- Crossley-Holland, Kevin (1999). The Anglo-Saxon World an Anthology. Oxford University Press. p. 264. ISBN 978-0-19-283547-5.

- Wolf Hall in the Domesday Book

- "Church of St. Mary, Great Bedwyn". Wiltshire Community History. Wiltshire Council. Retrieved 29 November 2015.

- "Church of St Mary the Virgin". historicengland.org.uk. Retrieved 30 September 2006.

- Historic England. "Churchyard Cross, Great Bedwyn (1034045)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 29 November 2015.

- Robert L. Martensen, ‘Willis, Thomas (1621–1675)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Oct 2007

- Historic England. "Church of St Katherine, Great Bedwyn (1183857)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 30 November 2015.

- "Brown Street Methodist Chapel, Great Bedwyn". Wiltshire Community History. Wiltshire Council. Retrieved 30 November 2015.

- Historic England. "School, Great Bedwyn (1300349)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 30 November 2015.

- "Great Bedwyn C. of E. Primary School". Wiltshire Community History. Wiltshire Council. Retrieved 30 November 2015.

- "St. Katherine's Church School, Savernake". Wiltshire Community History. Wiltshire Council. Retrieved 30 November 2015.

- "Grafton Primary School". Wiltshire Community History. Wiltshire Council. Retrieved 30 November 2015.

- "Where exactly was Wolfhall?". Wiltshire Community History. Wiltshire Council. July 2007. Retrieved 29 November 2015.

Further reading

- Aston, Michael; Bond, James (1976). The Landscape of Towns. Archaeology in the Field Series. London: J.M. Dent & Sons Ltd. pp. 59, 60. ISBN 0-460-04194-0.

- Crowley, D.A. (ed.); Baggs, A.P.; Freeman, Jane; Smith, C.; Stevenson, Janet H.; Williamson, E. (1999). A History of the County of Wiltshire: Volume 16: Kinwardstone hundred. Victoria County History. pp. 8–49.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Pevsner, Nikolaus; Cherry, Bridget (revision) (1975) [1963]. Wiltshire. The Buildings of England. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. pp. 255–257. ISBN 0140710264.

- Pugh, R.B.; Crittall, Elizabeth (eds.) (1956). A History of the County of Wiltshire, Volume 3. Victoria County History. p. 334.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Great Bedwyn. |

- Great Bedwyn at Wiltshire Community History (Wiltshire Council)

- Parish Council

- Village website

- Origins of Bedwyn – Ian Barnard