John Ball (priest)

John Ball (c. 1338[1] – 15 July 1381) was an English priest who took a prominent part in the Peasants' Revolt of 1381.[2] Although he is often associated with John Wycliffe and the Lollard movement, Ball was actively preaching 'articles contrary to the faith of the church' at least a decade before Wycliffe started attracting attention.[3]

John Ball | |

|---|---|

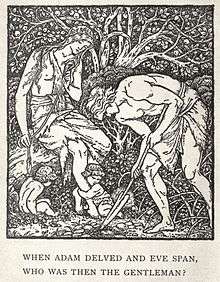

Medieval drawing of John Ball giving hope to Wat Tyler's rebels | |

| Born | c. 1338 |

| Died | 15 July 1381 (aged 42/43) St Albans |

| Nationality | English |

| Occupation | Priest |

| Known for | Peasants' Revolt |

Biography

John Ball was the son of William and Joan Ball of Peldon near Colchester. He is first mentioned in the Colchester Court Rolls of 30th January 1352, when, on coming of age in 1350 he acknowledged the tenancy of a tenement between East and West Stockwell Street in the town.[4] Ball trained as a priest in York and referred to himself, according to Thomas Walsingham, as "Seynte Marie prest of York". He later moved to Norwich and then back to Colchester. At that time, England was exhausted by death on a massive scale and crippling taxes; the Black Death was followed by years of war, which had to be paid for. The population was nearly halved by disease and overworked, and onerous flat-rate poll taxes were imposed.[5]

Ball was imprisoned in Maidstone, Kent, at the time of the 1381 Revolt.[2] What is recorded of his adult life comes from hostile sources emanating from the religious and political social order. He is said to have gained considerable fame as a roving preacher without a parish or any link to the established order[5] by expounding the doctrines of John Wycliffe, and especially by his insistence on social equality.[2] He delivered radical sermons in many places, including Ashen, Billericay, Bocking, Braintree, Cressing Temple, Dedham, Coggeshall, Fobbing, Goldhanger, Great Baddow, Little Henny, Stisted and Waltham.[5]

His utterances brought him into conflict with Simon of Sudbury, Archbishop of Canterbury, and he was thrown in prison on several occasions. He also appears to have been excommunicated; owing to which, in 1366 it was forbidden for anyone to hear him preach.[2] These measures, however, did not moderate his opinions, nor diminish his popularity, and he took to speaking to parishioners in churchyards after official services.[5]

Shortly after the Peasants' Revolt began, Ball was released by the Kentish rebels from his prison.[2] He preached to them at Blackheath (the peasants' rendezvous to the south of Greenwich) in an open-air sermon that included the following:

When Adam delved and Eve span,[lower-alpha 1] Who was then the gentleman?[6] From the beginning all men by nature were created alike, and our bondage or servitude came in by the unjust oppression of naughty men. For if God would have had any bondmen from the beginning, he would have appointed who should be bond, and who free. And therefore I exhort you to consider that now the time is come, appointed to us by God, in which ye may (if ye will) cast off the yoke of bondage, and recover liberty.[7][8]

When the rebels had dispersed, Ball was taken prisoner at Coventry, given a trial in which, unlike most, he was permitted to speak. He was hanged, drawn and quartered at St Albans in the presence of King Richard II on 15 July 1381. His head was displayed stuck on a pike on London Bridge, and the quarters of his body were displayed at four different towns.[5] Ball, who was called by Froissart "the mad priest of Kent," seems to have possessed the gift of rhyme. He voiced the feelings of a section of the discontented lower orders of society at that time,[2] who chafed at villeinage and the lords' rights of unpaid labour, or corvée.

Ball and perhaps many of the rebels who followed him found some resonance between their ideas and goals and those of Piers Plowman, a key figure in a contemporary poem putatively by one William Langland. Ball put Piers and other characters from Langland's poem into his cryptically allegorical writings which may be prophecies, motivating messages, and/or coded instructions to his cohorts. This may have enhanced Langland's real or perceived radical and Lollard affinities as well as Ball's.

John Ball in popular culture

Ball is also mentioned at John Gower's Vox Clamantis line 793. Morley translates this as:

Ball was the preacher, the prophet and teacher, inspired by a spirit of hell,

And every fool advanced in his school, to be taught as the devil thought well.[9]

Ball appears as a character in the anonymous play The Life and Death of Jack Straw, published in London in 1593, which deals with the events of the Peasants' Revolt.

William Morris wrote a short story called "Two extracts from a dream of John Ball", which was serialised in the Commonweal between November 1886 and February 1887. It was published in book form in 1888.

English songwriter Sydney Carter wrote an eponymously titled song about Ball that has been recorded by a number of artists.[10] 'Sing John Ball' is regularly performed in the UK by folk musicians including The Young'uns, The Melrose Quartet, and in 2015 the group Sweet Liberties performed the song in the Houses of Parliament.[11]

There is a steep hill on the A5199 road in Leicestershire, between Shearsby and Husbands Bosworth, that is colloquially called "John Ball Hill".

A tower chapel at the parish church of Thaxted in Essex was dedicated to John Ball under the Anglo-Catholic socialist vicar, Conrad Noel (1910–1942).

The Bedfordshire on Sunday, a free local newspaper based in Bedford, runs a weekly column by a fictional journalist called "John Ball's Diary", which features behind-the-scenes life in the office of the newspaper. The column is written by all the members of the editorial staff.[12]

John Ball appears in the 1954 historical novel Katherine by Anya Seton.

Ball made an appearance in the Newbery Medal-winning 2002 novel Crispin: The Cross of Lead. He was a priest, as he usually is, and was assisting a character by the name of Bear in the Peasants' Revolt of 1381.

John Ball is referenced several times in T. H. White's The Once and Future King, most prominently in the fourth book, The Candle in the Wind. In the final chapter (14), King Arthur muses on his failure to unite England. King Arthur tries to understand what forces are at work that make mankind fight wars and references the "communism" of John Ball as a precursor to Mordred's Thrashers.[13]

John Ball's line, "When Adam delved and Eve span, Who was then the gentleman?" serves as the epigraph to Zadie Smith's 2012 novel NW, which follows characters who grew up on a council estate in northwest London.

In Act V Scene 1 of Hamlet, Shakespeare has the Gravedigger (First Clown) discuss the line "When Adam delved and Eve span, Who was then the gentleman?" with a bit of a reversed sense: in Adam's time there were none but gentlemen.

First Clown: ... Come, my spade. There is no ancient gentleman but gardeners, ditchers, and grave-makers: they hold up Adam's profession.

Second Clown: Was he a gentleman?

First Clown: He was the first that ever bore arms.

Second Clown: Why, he had none.

First Clown: What, art a heathen? How dost thou understand the Scripture? The

Scripture says 'Adam digged:' could he dig without arms?

See also

Notes

- Delved meaning dug the fields, and span meaning spun fabric (or flax).

Citations

- Busky 2002, p. 33.

- Chisholm 1911, p. 263.

- Larsen, Andrew E. (2003). Lollards and their influence in late medieval England. Somerset, Fiona., Havens, Jill C., 1967-, Pitard, Derrick G., 1964-. Woodbridge, Suffolk, UK: Boydell Press. p. 63. ISBN 0851159958. OCLC 51461056.

- 'A Colchester Rebel; A Short Study of John Ball - sometime parochial chaplin at St James' Church, Colchester' by Brian Bird, Rector of Groton

- Vine 2014.

- "When Adam delved and Eve span,/Who was then the gentleman" Sources

- Chisholm 1911, p. 263

- Webster's online Dictionary Archived 12 May 2005 at the Wayback Machine

- The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition. 2001

- The Columbia World of Quotations. 1996

- BBC: VOICES OF THE POWERLESS – READINGS FROM ORIGINAL SOURCES

- English Literature by William Joseph Long

- Other versions

- "When Adam dalved and Eve span, / Where was than the pride of man?" Richard Rolle de Hampole. Little Oxford Dictionary of Quotations online claims that this is the original source for Ball's version.

- "When Adam dalf, and Eve span, / Who was thanne a gentilman?" from Thomas Walsingham's Historia Anglicana (Paul H. Freedman. Images of the Medieval Peasant, Stanford University Press, 1999 ISBN 0-8047-3373-2. p. 60)

- "When Adam dolve, and Eve span, / Who was then the gentleman?" John Bartlett, comp. (1820–1905). Familiar Quotations, 10th ed. 1919. Page 871 from Hume: History of England, vol. i. chap. xvii. note 8.

- "When Adam dug and Eve span, / Who was then a noble man?" Literature of Richard II's Reign and the Peasants' Revolt. Edited by James M. Dean

- Notes and Queries, Vol. 7 3rd S. (171) Apr 8 1865 Page 279, Oxford University Press, 1865, "Delved Dolve or Dalf?" by N.N.

- BBC: Voices of the powerless – readings from original sources

- Dobson 1970, p. 375 quotes from Thomas Walsingham's Historia Anglicana:

When Adam dalf, and Eve span, who was thanne a gentilman? From the beginning all men were created equal by nature, and that servitude had been introduced by the unjust and evil oppression of men, against the will of God, who, if it had pleased Him to create serfs, surely in the beginning of the world would have appointed who should be a serf and who a lord" and Ball ended by recommending "uprooting the tares that are accustomed to destroy the grain; first killing the great lords of the realm, then slaying the lawyers, justices and jurors, and finally rooting out everyone whom they knew to be harmful to the community in future."

- Henry Morley (1867). English Writers (Volume 2, pt. 1). General Books LLC. p. 44. ISBN 978-1235028014.

- "John Ball [Sydney Carter]". mainlynorfolk.info. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

- "Sweet Liberties Launch, Speaker's House, Palace of Westminster, 16th November". Folk Radio UK. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

- "John Ball's Diary". Local Sunday Newspapers. Archived from the original on 27 July 2011. Retrieved 18 July 2011.

- The Once and Future King by T. H. White.

References

- Busky, Donald F. (2002). Communism in History and Theory: From Utopian Socialism to the Fall of the Soviet Union. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 33. ISBN 0-275-97748-X.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dobson, Richard B. (1970). The Peasants Revolt of 1381. Bath: Pitman. pp. 373–375.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Vine, Richard (4 August 2014). "Melvyn Bragg's Radical Lives review – a Chaucerian delight". The Guardian.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Attribution

- Thomas Walsingham, Historia Anglicana, edited by Henry Thomas Riley (London, 1863–64)

- Henry Knighton, the Chronicon, edited by Joseph Rawson Lumby (London, 1889–95)

- Jean Froissart, Chroniques, edited by S. Luce and G. Raynaud (Paris, 1869–97)

- More modern version published by Penguin Classics, 1978. ISBN 0-14-044200-6

- Charles Edmund Maurice, Lives of English Popular Leaders in the Middle Ages (London, 1875)

- Oman, Charles (1906). The Great Revolt of 1381. Clarendon Press., Republished Oxford University Press, 1969

External links